The Currents

A woman, beautiful and a touch removed, travels to Switzerland from Argentina to accept an award. She throws the glass statuette in the bathroom trash, then leaves the ceremony to wander the streets. Clad in a vivid blue coat, she stands out from the grey cobblestone streets she traverses. A quiet storefront captures her attention. Its window, amber-lit against the murky day, shows a piece of cloth stitched with an image of people sewing. She continues on her way, and while crossing a bridge over a churning river, she hoists herself over the railing and plunges into the water. The police rescue her and deliver her back to her hotel wrapped in a shimmering, gold thermal blanket. She tries to take a shower, but the water running down the drain triggers something in her, and she turns off the tap. She has not spoken one word.

This is the stunner of an opening for Argentinian director Milagros Mumenthaler’s new film, The Currents, and the film follows the aftermath of this woman’s plunge. Catalina (Isabel Aimé González-Sola), a fashion designer and artist, develops a suffocating phobia of water, preventing her from focusing on her work or being present with her husband, Pedro (Esteban Bigliardi), and her young daughter, Sofía (Emma Fayo Duarte). Writer-director Mumenthaler maintains a degree of opacity in how she depicts Catalina; the story is never entirely linear and Catalina’s sudden jump and lingering aversion to water are never entirely explicable. What she does capture—sometimes powerfully, sometimes a touch too obliquely—is Catalina’s distance from the external world and from her own interior life. How does a person move on with their life, Mumenthaler prompts us to question, when they suddenly feel that they are being swept along by forces stronger than their own will?

Mumenthaler follows Catalina through the routines of her home and work life as she struggles to maintain equilibrium. While, at first, her family and colleagues do not seem to notice a difference in her, González-Sola effectively portrays how her character works diligently, to diminishing returns, to bury her all-consuming fear of water under an anodyne exterior. What truly poses a stumbling block in her daily life is her long, thick hair, which she has not washed in days and is causing her skin irritation and self-consciousness. It seems like an oddly surface-level emphasis, but it rings true that the most immediately deleterious effect of Catalina’s anxiety is an energy-consuming struggle to go through the basic motions of caring for herself.

While psychologically insightful, it becomes cinematically uninteresting to watch Catalina navigating her mental block. González-Sola’s performance is recessive to the point that her screen presence sometimes comes across as flat; though she portrays her character’s masking of her fear convincingly, she is still muted even in unguarded moments, placing the viewer at a distance that is just slightly too far. This distancing performance aligns with Mumenthaler’s narrative strategy; she never gives full insight into what may have spurred Catalina’s leap into the water, and is almost as withholding about what self-reflection, if any, it spurs in Catalina. While seeming to reach for an intriguing ambiguity, Mumenthaler ultimately overshoots and lands in vagueness, leaving the viewer with an understanding of Catalina that is almost as limited as in the film’s enigmatic opening.

Though Mumenthaler’s narrative strategy is flawed, her visual strategies are often striking. With director of photography Gabriel Sandru, she crafts a number of shots that clearly reference Hitchcock’s Vertigo (as does the plot itself). Sandru accordingly captures color in a way that is as vivid and enrapturing as Robert Burks’ photography for Hitchcock’s film, with electric blues, verdant forest greens, and deep crimsons providing both visual and subtextual texture to otherwise cryptic scenes.

The silent opening Mumenthaler crafts is one of the film’s two strongest sequences, aesthetically and narratively; the other equally striking scene is an unusual slip into surrealism that occurs in a lighthouse that is, oddly, at the top of Catalina’s apartment building. Catalina has followed Sofía up there, who claims she can see Catalina’s employee, Julia (Ernestina Gatti), walking on the street, despite how far from the ground the lighthouse is. Catalina then starts to drift into a state of semi-consciousness, where she sees the searchlight casts its light on Julia and a series of other people she knows, providing a golden-lit glimpse of what each of them are presently doing. There is not a simple or clear explanation for why this scene occurs, or what it even reveals about Catalina’s state of mind. Yet it is beautifully executed by Mumenthaler and Sandru, and the inexplicable peeks into the routines of minor characters provides a fascinating counterpoint to Catalina’s difficulty navigating her own life. Catalina may not understand what these visions of others’ daily lives mean, but they make an indelible subconscious impact. At its best, Mumenthaler’s flawed but fascinating film delivers the same effect. — ROBERT STINNER

Honey Bunch

Filmmaking duo Madeleine Sims-Fewer and Dusty Mancinelli took the 2020 TIFF Midnight Madness crowd by storm with their stunning debut feature Violation, an extremely dark, extremely violent exploration of trauma that transforms into a vicious revenge thriller. They’ve changed pace a little bit for their new film Honey Bunch, a curious little mind-bender that mixes and matches a huge number of genre influences with modest success. It’s a shaggy movie, overlong and sometimes frustratingly familiar in the tropes it deploys, but it also gets better as it goes along and begins to transform into something deeper than mere pastiche.

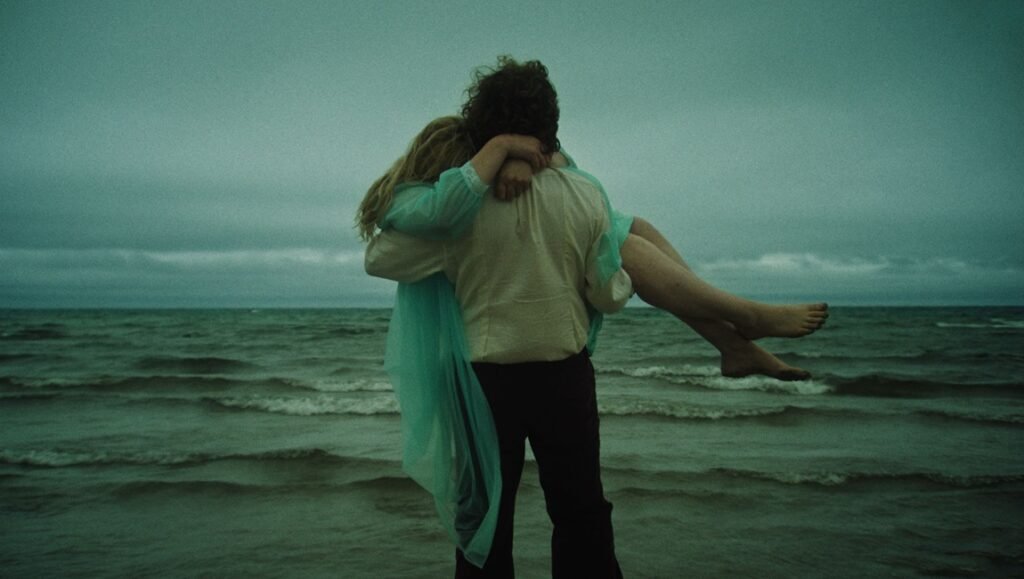

As the film begins, we see a man carrying a woman from her wheelchair and into the ocean. He kisses her, tells her that he loves her, and then seemingly submerges her into the water. We then cut to a couple driving through a wooded countryside; the same man from the cold open is behind the wheel here, speaking to a woman who looks a lot like the one we just saw being plunged to her (presumed) death. They are Diana (Grace Glowicki) and Homer (Ben Petrie), and they are travelling to a special institute for traumatic head injury victims. Diana had been in a coma after an undisclosed accident, and now has severe gaps in her memory. They are hoping that specialized care will help her recover some of these memories, as well as help with a pronounced limp that requires the use of a cane. They soon arrive at an imposing mansion, and are greeted by Farah (Kate Dickie), the keeper of the building and assistant to the renowned doctor who will be providing Diana’s care.

It’s all very mysterious and ominous, from the dark color grading of the image itself to the horror-infused soundtrack. Sims-Fewer and Mancinelli shoot the mansion like a gothic horror movie, all dark corridors and long, winding hallways. Portraits of the doctor’s deceased wife hang in every room, gazing down upon the patients. Diana and Homer settle in, even joking about how Farah reminds them of Mrs. Danvers from Hitchcock’s Rebecca. Soon, a man named Joseph (Jason Isaacs) arrives with his daughter, Josephina (India Brown). She too has suffered a head trauma, and begins engaging in memory recovery sessions and physical therapy with Diana.

Honey Bunch offers a fairly straightforward setup, but the filmmakers almost instantly begin playing narrative and formal tricks meant to mimic Diana’s fragile mental state. She loses time, sitting in a bathtub in broad daylight and then snapping to in total darkness. Homer will excuse himself and leave a room and suddenly reappear after what seems like either seconds or hours. Further, Diana seems to be seeing things that aren’t actually there (or are they?); a body crouches in a dark corner and vomits, while figures appear fleetingly in windows or in doorways. A stroll through the lush surrounding forest winds up at a dangerous precipice, as the trail dead-ends at a precarious cliff overlooking a waterfall. What exactly is going on here, and why does Homer seem to already know Farah and Joseph? Everyone seems to be hiding something, including the fate of the good doctor’s beloved wife, who may or may not have committed suicide at that very same waterfall. The various narrative threads grow thick with innuendo and creepy vibes, culminating in a sort of fugue state involving brain surgery that may or may not have happened. Are these hallucinations? Visions? Memories?

Glowicki and Petrie, both accomplished filmmakers in their own right and a real-life couple, give offbeat, peculiar performances. They feel particularly modern, despite the film being set in a nebulous time period, with several details signifying the late 1970s. For their part, the filmmakers are certainly playing with a specific kind of ‘70s-era British horror film aesthetic (lots of quick zooms and soft, diffuse lighting). It’s a strange mixture, sometimes approaching a less visually aggressive approximation of someone like Peter Strickland. But the leads are charming enough that one can’t help but root for a conventional happy ending.

Things seem to reach a dramatic head at roughly the one-hour mark, at which point the film fully reveals exactly what’s going on here and for all practical purposes changes genres in the process. It’s not a twist, not exactly, but to reveal exactly what happens would be a huge disservice to future audiences. Suffice to say, the entire second half of the film drastically alters what we think we know about Diana and Homer, plumbing thematic material that makes the film a closer companion piece to Violation than it might initially appear. One wishes the first half wasn’t quite so distended, especially as many of the tricks being played wind up being red herrings (what’s the opposite of Chekov’s Gun?). Still, there’s a pretty appealing anything-goes approach to the storytelling here that works overtime in the film’s favor. For those willing to go on a bumpy ride, Honey Bunch’s final destination should make the journey worthwhile. — DANIEL GORMAN

Blue Heron

“Seeking to reduce a filmmaker’s chief thematic preoccupation is usually a waste of time, for any one worth their stuff works in a storm of competing and converging interests that, if they’re lucky, alights on the ground every few years in a distinct, feature-length form. Alexandre Koberidze, whose third feature, Dry Leaf, premiered at this year’s Locarno Film Festival, is no different. Since his feature debut in 2017, he’s established himself as a leader in a loosely articulated Georgian New Wave, whose characters are caught up in, and asked to navigate, the shifting ground of their national identity, modernity, tradition, progress, regress, and romance…” [Previously Published Full Review.] — CHRIS CASSINGHAM

Forastera

The debut feature from Spanish director Lucía Aleñar Iglesias is a different kind of coming-of-age story, one that finds its young protagonist Cata (Zoe Stein) taking an unexpected turn in the trajectory of her maturity. She and her younger sister Eva (Martina García Cursach) are spending the summer on the Spanish coast with their grandparents, and in the midst of a fun, casual time with the family — card games, sewing clothes, hanging out on the beach — Cata’s beloved grandmother (Marta Angelat) has a sudden fall and dies. Forastera (Spanish for “stranger” or “outsider”) is a deftly observed story about the different forms that grief can take, and how in moments of tragedy, some of the oldest and most pernicious patterns of family behavior suddenly assert themselves, undoing years of healing and sending us back to factory specs.

We see much of this tension flaring up between Cata’s grandfather Tomeu (veteran actor/Almodóvar alum Lluís Homar), a retired airline pilot, and Pepa (Nuría Prims), the girls’ mother, a somewhat tightly-wound event planner. Part of the conflict is situational, as Pepa thinks it would be best for Tomeu to sell the family home and move somewhere smaller and safer. Tomeu understandably resents Pepa’s suggestion that he cannot take care of himself. But it’s clear that the animosity between father and daughter runs deeper than that. When Tomeu speaks to Cata about his late wife, he speaks of her traditional manner, how she loved being in the kitchen, cooking and sewing and caring for others. One gets the feeling that Tomeu perceives Pepa as a closed-off career woman, judging her for making different choices.

Cata, Eva, and Pepa go through Catalina’s clothes and the girls start trying things on. For Eva, this is just dress-up, but something happens to Cata when she wears her grandmother’s dresses. She feels closer to her, and this activates unconscious inklings about a new role in the family. At 17, Cata doesn’t quite know who she wants to be, and crass as it may be to say, the death of her grandmother represents an opening for her to subtly slot herself into. Iglesias suggests early on that Cata may be starting to over-identify with Catalina, and not just because they have the same name. Twice — once on a call with Pepa, another time with a hairdresser phoning about an appointment — Cata answers her grandmother’s call and is mistaken for the older woman.

Forastera wisely steers clear of classic psychological or supernatural themes of identity swapping — Persona and Mulholland Drive being the most obvious examples. Cata’s confusion about who she is and who she’s meant to be is depicted in extremely normal terms, even though it’s clearly not a healthy path for her to take. Part of Cata’s occupation of Catalina’s role entails being a buffer and would-be peacemaker between her mother and grandfather, something very common in dysfunctional families. A young person often tries to take on the parental role as a way to combat a sense of helplessness. Although Iglesias sidesteps any notions of haunting or possession, she also shows that those ideas are powerful ones that people in pain can adopt as ways to explain the inexplicable. Catalina and Tomeu’s flickering fluorescent light in the kitchen, which they jokingly called their “ghost,” takes on new meaning for Cata, even though the cause is obviously electrical and not metaphysical.

This speaks to Iglesias’ surefooted writing and direction. She is not interested in using a family tragedy to spin a fanciful tale. But she does show how we can easily succumb to magical thinking when we are at our most vulnerable. In the opening shot, Cata and Eva are lying on the beach. Cata tells Eva that she saw a dolphin the other day while out in her kayak. Eva doesn’t believe her. Later, we see Cata encountering the “dolphin” again and see that it is an inflatable pool toy, “real” but fake. Cata understands the difference between reality and representation, the material and the symbolic. But unsettled as she is, she has decided to suspend that difference, and repair to the world of make-believe, and embrace the outsider within herself. — MICHAEL SICINSKI

Calle Málaga

Maryam Touzani’s Calle Málaga won the Audience Award at the Venice Film Festival’s new Spotlight Section, and the film is accordingly an audience-pleaser. Following her delicate depiction of a queer love triangle unsettling a longstanding marriage in The Blue Caftan, which was the first Moroccan film to be shortlisted for the International Feature Academy Award in 2022, Touzani’s new film is an equally sensitive character piece. A heartfelt, but not oversentimental, portrait of a septuagenarian woman reconnecting with her community and her desires, Calle Málaga is easy to embrace. The film contains vibrancy and poignancy in equal measure, and if reliant on familiar plot beats, Touzani is a sophisticated enough filmmaker to use the film’s occasional predictability to her advantage, providing an opportunity for a wide audience to engage with thoughtful ideas about diasporic communities, late-in-life sexuality, and contentious familial relationships within a comforting narrative frame.

A title card at Calle Málaga’s onset explains the cultural context of its setting, Tangier, a city in northern Morocco. A short distance from Spain, the city has long been a “melting pot” of cultures due to its location and its previous statuses as an international city, then Spanish protectorate, prior to Moroccan independence. A large Spanish population settled in Tangier in the 1930s at the onset of Francisco Franco’s dictatorship, and the film focuses on a descendant of this Spanish community who calls Tangier home.

María Angéles, played by the estimable Carmen Maura, is a woman in her 70s who has lived in the same flat in Tangier for 40 years. Widowed and with an adult daughter who lives in Spain, she spends much of her time alone, but has a close bond with her neighbors and takes clear pleasure in the simple tasks of daily life like shopping at the market, cooking, and listening to records. A sudden visit from her harried daughter, Clara (Marta Etura), upends her placid lifestyle. Clara is a healthcare worker with two children who is struggling financially amid a contentious divorce. Her father left the flat María Angéles still lives in to Clara upon his death, and so Clara decides to sell it against María Angéles’ wishes in order to purchase a flat of her own. Unwilling to move to Madrid with Clara, María Angéles briefly stays in a local retirement home, but cannot withstand the circumscribed lifestyle enforced there. Set on living her life to the fullest no matter the limits of her circumstances, she makes a hasty return home without Clara’s knowledge, starts buying back her furniture, and hides whenever a realtor shows the flat to prospective buyers.

The film revolves around María Angéles’ personal development as she adapts to her precarious new circumstances, and Maura fills the role with an unassuming, yet compelling depth. Touzani lingers on her face in numerous close-ups throughout the film, and Maura, best known in the United States for her roles in several Pedro Almodóvar films, expresses a deep internal life through the slightest of micro-expressions — for example, though María Angéles barely speaks to Clara after she learns of her plans to sell the flat, Maura communicates the suffocating disappointment she feels with silent, cutting clarity. Maura embodies a full range of emotions as María Angéles gains new experiences; she is boisterous when hosting an informal café for soccer fans in her apartment for extra cash, and sensual when falling into an affair for the antiques dealer (Ahmed Boulane) she has been buying her furniture back from. This relationship is the most affecting subplot in the film, handled with grace and refreshing eroticism. While the sexuality of older people is used as a punchline or, worse, a jump-scare in many other films, Touzani’s treatment of this subject matter is near-reverent, allowing Maura and Boulane to create a believable, appealing intimacy.

While María Angéles thrives after grabbing her last chance at an independent life, Clara does, of course, re-enter the narrative, forcing María Angéles to consider how to move forward, and Clara to take a closer look at her mother’s perspective. Through this contentious relationship, and how it plays out over the film, Touzani, herself a native of Tangier, sets up a pertinent conflict without an easy resolution. Clara does not share María Angéles’ devotion to her home city, and she does not comprehend why her mother stays in a city with few surviving friends, rather than move to Madrid with her. The mother and daughter stand in for a broader generational conflict between longstanding community roots and immediate economic need, and María Angéles and Clara’s polar perspectives cannot be simply reconciled. Touzani, though, creates a wealth of sympathy and understanding for María Angéles’ position, and in doing so paints a touching portrait of a dwindling diasporic community. As much a personal tribute to Touzani’s home city as it is an affecting showcase for Carmen Maura, Calle Málaga satisfies on both levels. — ROBERT STINNER

A Useful Ghost

“One day, noticing an influx of dust into their apartment due to some construction outside, a person known only as an “academic ladyboy” (as they call themselves and are credited on IMDb) buys a new vacuum cleaner. It seems to work well, but that night the vacuum coughs out all of its dust. A call to the shop brings a repairman almost instantly, who informs them and us that the machine is probably haunted. In fact, the whole factory where it was built is haunted. He relates the story of one ghost, a vengeful spirit who died at work and…” [Previously Published Full Review.] — SEAN GILMAN

Palestine 36

“The year you were born,” reads the opening title card to Palestine 36. It’s a daunting prescription that also invites the viewer into the story. Director Annemarie Jacir’s film doesn’t follow just one character, nor is it stuck in the second-person, so it’s unlikely that the “you” is meant to refer to any of the film’s many pre-Nakba Palestinian characters. And while Jacir’s film is perhaps the most comprehensive and valuable narrative drama to survey the origins of Palestinian subjugation in the Levant, it also doesn’t start, strictly speaking, from the most commonly accepted naissance of the issue: the 1917 Balfour Declaration. What exactly is being born in 1936 though? Arab and Palestinian resistance to the (pre-statehood) Israeli settler occupation of their land.

The historical consensus on the Great Palestinian Revolt is that it began in 1936 and lasted through 1939. To oversimplify, the resistance started with economic and political resistance within the system established by the British Mandate (or, in some cases, carried over by the British from the Ottoman). The general strike lasted from April to October and at the time could have been the longest general labor strike in economic history. The resistance then became violent, tearing apart the cohesion of the Arab community in the process. Two forms of resistance take center in Palestine 36.

The cast of characters here is intentionally vast, covering all facets and political persuasions in 1930s Palestinian life. A few of the more important roles include Fr. Boulos (Jalal Altawil), an Eastern Rite Catholic priest (which means he can marry and have children); the wealthy colluder Amir (Dhafer L’Abidine); Khouloud (Yasmine Al Massri), Amir’s wife and a popular left-wing newspaper writer with a male pseudonym; and Yusuf the farmer (Karim Daoud Anaya). Together they represent the many faces of Palestine: the Christian and the Muslim, the farmer and the businessman, the husband and wife, the militant rebels and the traitors. Jacir and her editor Tania Reddin carefully edit Christian and Muslim religious rituals in sequence with each other, as if to emphasize the shared destiny and political aspirations of the two groups of worshippers.

Palestinian history broadly is integral to Jacir’s comprehensive account of the conflict’s origins: the discovery of illegal weapons shipments, the establishment of the Palestine Broadcasting Service, the Peel Commission, settlers setting fires to clear fields, and the deportation of leaders to the Seychelles. Those looking to better understand the historical context for the modern ethnic cleansing of Gaza will find Jacir’s film to be a valuable resource. It’s at its most powerful in the visualization of the land as fully Palestinian. Jacir and her team of three cinematographers barely show the Jewish settlers on screen; the British, and their military cars and imperial suits, creep into the picture much more frequently. The archival footage Jacir stitches into the narrative showing life in 1930s Palestine reiterates just how Palestinian the land is: in language, in religion, in clothing. Of course, anyone who is paying attention and knows anything about the history of the Levant already knows this, but it is another, more powerful thing to see it. The steppe terraces of Battir, a complex irrigation system carved into the valleys over generations and now recognized by UNESCO, communicate this most effectively. (An elder member of the community makes sure to point this out, in case it wasn’t clear already.) The Palestinians have been here so long that they have changed the earth itself; the settlers burn it as if it needs cleansed before they can start anew.

The face of the enemy here is the cruel Captain Wingate (Robert Aramayo). Liam Cunningham and Jeremy Irons also play supporting roles as British villains, putting their star power to action in support of Palestine. As his film premieres at the 2025 Toronto International Film Festival, Cunningham is on the international flotilla trying to break Israel’s blockade. There is a nod in the film to the British’s handling of Ireland, and one wonders if this nod of solidarity was inspired by Cunningham’s real-life solidarity. The most intriguing Brit though is Thomas Hopkins (Billy Howle), the one who takes the correct moral position and becomes closer and closer to the Arab community he holds power over. He becomes complicit in the violence when he decides to leave Palestine and retire his political advocacy for them. His beliefs don’t change; he is just so frustrated with his inability to effectuate change through his superiors that he quits the cause. It’s tough not to think of Thomas as the modern analogue: it’s one thing to have the right beliefs, it’s another thing to act on them. — JOSHUA POLANSKI

Wavelengths 2: Into the Blue

Wavelengths 2: Into the Blue, more than either of the other 2025 shorts programs or the features, exemplifies experimental film programming’s recent trend toward documentary, essay, and other “non-fiction” forms. All of the films in this program explore, in some fashion, the moving image as archive, memory, or trace of what came before.

The program opens with I Saw the Face of God in the Jet Wash, a diaristic short from Mark Jenkin, whose latest feature (Rose of Nevada) is also screening in Toronto. Speaking at rapid clip, Jenkin narrates over bits of grainy 16mm footage taken during his filmmaking travels, discussing his screenings, the mostly unadventurous happenings of trips around them, trivia about other filmmakers in the places he visits, and so on. Several of his films are referenced quickly in passing, by detail rather than title: “the stone film,” “my short film about the homeless couple.”

The peripheral nature of this footage and these anecdotes are the core of the film. The artist finds inspiration for his fantastical, elliptical films in all this mundane material. A statue near a campsite seems to have moved overnight and he wonders about its sentience later. But this never becomes a genre film of the sort Jenkin is known for. It is rather a wry and modest work for the amusement of fellow nerdy cinephiles. It relies tonally on comical shifts of syntax, and even more on references to classic movies. A boat is wrongly supposed to have been used in a Skolimowski film; Hitchcock was on vacation here once and he (Jenkin) thinks about Rebecca and what he’d do differently if he made a version; was this house a location for Baywatch? Jet Wash is charmingly insubstantial. It works well enough in a shorts program, but it might work even better as an appetizer for a feature film. Dare we hope that whoever buys Rose of Nevada takes this too?

Like Jenkin’s film, Minjung Kim’s From My Cloud is built from the odds and ends of the artist’s personal moving image archive, but is aesthetically opposite, in high-resolution digital photography. The title is a double entendre: these clips are from Kim’s digits media cloud, but also refer to a rain cloud, as described in text on the opening frame. The hodgepodge, observational nature of the source material is clear, but so are the formal connections that bind each cut. A spinning medallion becomes a spinning light which becomes a spinning camera. Swirling snowflakes cut to floating clouds of bubbles. The links are too clear. It’s easy to see the path Kim has found through the maze of her materials, but not what it adds up to. The strongest image here is the most obscure: a nocturnal, out-of-focus shot of a waterline with a series of distant lights blurred into small orbs. Here’s some of the mystery the rest of the film lacks, and which defines the strongest features in Wavelengths this year (Dry Leaf, Levers).

Cairo Streets is similarly drawn from personal archives but more explicitly tied to the artist’s biography. At the beginning, text announces that a narrator has returned to Cairo and misses someone named Omar that the narrator knew here before. Shot on a small, handheld camcorder, which we see occasionally in mirrors, this sort of DV realism is so in vogue that it’s easy to assume this is new footage until Youssef Chahine (who died in 2008) shows up for a quick chat in his office. Everything after this moment takes a slightly different tone, as we realize this is 18 year old material and likely sourced from the artist’s previous time in Cairo, rather than a newly composed essay. This also makes better sense of both subsequent and following scenes, which indeed feel like the random things a young person would capture with a camcorder in 2007: street vendors waving, a conversation with an older relative, and so on. Eventually someone who might be Omar shows up alongside the artist. But while there’s a soft sense of the phantoms of a queer coupling that didn’t or couldn’t last, there isn’t enough to give an audience investment in the weight these memories obviously hold for their creator.

Daria’s Night Flowers is another essay-adjacent work featuring archival materials with added text, but it’s easily the strongest of the bunch. It’s also distinct from the rest of the program in that, like Maryam Tafakory’s previous two films, the source materials are not the artist’s own media library but the national cinema of Iran. Clips from a variety of Persian films both classic and (one assumes) obscure are tied together by an imposed narrative. A woman, Daria, has written a novel about a lesbian romance, which is discovered and read by her husband. He takes it as literal and burns the manuscript, but she has secretly sent the final chapter to a friend. Daria kills herself through prescription overdose, and her story is told in retrospect through these fragmented texts and images.

The film clips themselves are edited in fairly close alignment to the story as told. A variety of actresses and actors stand in for Daria and her husband and doctors, but it’s always clear enough what’s happening. The film’s power comes less from its actual narrative than, first, the way its composition emphasizes what narratives couldn’t historically be told in Iranian cinema, and second, the mysterious details that elaborate both images and story. Splotches of bright yellow and blue stain the screen like a dye, and plants appear repeatedly in narrative detail or digression, playing a perhaps lethal, perhaps magical role. Night Flowers recalls another wonderful recent experimental film that blurs narrative and essay, Nour Ouayda’s The Secret Garden, in this botanical detail as well as aesthetically and in its allegorical character.

The program ends with its shortest film, Kaiwen Ren’s Aftertide. Less textual and essayistic than the other films, it shares their concern with records and traces in formal connection, albeit at a higher level of abstraction. It opens with what is perhaps its best, and certainly its most ambiguous, sequence, of flickering, angular, crystalline shapes whose content is indiscernible but seems to be displayed on an old video monitor, and sound cues suggest this is underwater. Cut to a figure dancing away from a wall and leaving a shadow static in place, and then a textured surface which gradually reveals itself to be some sort of non-photographic printing capturing vines and what might be a squid or a fishing lure. It’s hard not to think of Erica Sheu’s Transcript at this point, and Ren is similarly interested in how physical beings and materials — and the means by which humans observe them — leave their less substantial mark as images.

The middle of Wavelengths’ three shorts programs is perhaps its weakest — it certainly never reaches the dazzling heights of Morgenkreis or FELT in the third program — but still displays the thoughtfulness of good programming that allows the films to be more than the sum of their parts. That’s true not just of the connections between them, but of the differences. Switching from 16mm to high-definition digital to camcorder to found footage while maintaining a clear thematic throughline allows each of these films to emerge in its specificity and illuminate what works, or doesn’t, in the rest of the program. This is a vital experience and platform for films of such awkward length, form, and commercial invisibility. Let’s hope that Wavelengths expands rather than continuing its contraction, and that local and regional festivals commit to including elements of such adventurous programming.— ALEX FIELDS

Nino

“Biblical scholars and theologians use “antediluvian” to describe the world of Genesis between the fall from Eden and the flood. Literally meaning “before the flood,” the word packs grand meta-narratives of historical and cosmological significance: humans fumbled the chance to live in paradise for good and brought down our world with it. Disaster awaits, monsters lurk. The beauty of the original creation still radiates brightly in the meantime. This is the world that Momoko Seto’s Dandelion’s Odyssey drops into…” [Previously Published Full Review.] — PATRICK FEY

Comments are closed.