The biography of an artist is an artist’s nemesis. It aims a howitzer at artists and the body of their work. In its illuminating, explicatory nature, it renders legible what had seemed sui generis; in reams of helpful context, it forces its subject into a set of coordinates, locating their inspiration in time and space. If the artist is still living, the publication of a biography stands as the first announcement of their death, marking the end of a certain freedom to self-define. Worse still, if the artist has a reputation for being “reclusive” — that is, if the artist is wary of the press, eschews interviews, avoids photography — then the event of their biography represents a notable defeat. An invasion of privacy: what else is new? But taken together with its other antagonisms, the biography represents an orbiting threat. The jig is up. Extinction is here.

As a critic, I’m wary of the dangers of drawing lines between a biography and an artist’s work. It feels lazy, inattentive, an invitation for the worst kind of psychologizing. When the artist in question is Terrence Malick, director of 10 films of various degrees of perplexity, a man whose life, and whose absences, are shrouded in near-parodic mystique, then the dangers of analysis seem that much more pronounced. Contextual criticism, Intentionalism, whatever the opposite of New Criticism is — in all cases, there’s something parasitical about leeching insight from a biography in order to explicate artwork (and vice-versa).

Then again, what is a critic if not a species of bottom-feeder? The danger is not exploitation, but its opposite: agreeability. By ignoring an artist’s biography, we risk drawing too little blood, we risk never sinking our teeth into an artist whose corpus is a whale to be reckoned with. Malick is arguably a major artist, certainly a hugely influential stylist, and his life — documented in John Bleasdale’s new biography, The Magic Hours: The Films and Hidden Life of Terrence Malick — is rich enough and odd enough to warrant an investigation into the ways in which his private concerns have infused his art.

If I were to ascribe an overriding theme to Malick’s life and his work — and I’m not sure that I should — it is freedom. Freedom from the authority of his overbearing father; wild adventurousness in his years at Harvard and beyond; and an astonishing creative independence, including the freedom from work itself — famously, a 20-year gap elapsed between his second and third films. Malick’s life is also an object lesson in the costs of such freedom, the ways in which experimentation is gleefully punished. The three films of his Weightless Trilogy — To the Wonder (2012), Knight of Cups (2015), and Song to Song (2017) — take extraordinary formal liberties, dispensing almost completely with narrative, continuity, and visual logic; as a result, they were summarily skewered by most critics and completely ignored by audiences. I’m not here to praise or defend those films, which are exquisite and embarrassing in equal measure. What interests me is the artist’s spree — his crimes and punishments.

As the biography makes clear, Malick struggled heavily against the burden of family history. Born in 1943, he was, on his father’s side, the grandson of Assyrian immigrants who’d escaped genocide in Ottoman Persia, and the matrilineal descendant of hardscrabble Irish-Canadian farmers who raised crops in Illinois. His parents, Emil and Irene, were both first-generation college students, though neither of them finished their degrees; Malick’s father, an unusually gifted student, was forced to leave MIT in order to support his family after his father, Ablimech, was laid off from his job. Emil got a position as a research and development engineer for Bendix Aviation Company before enlisting as a Navy aviator during World War Two, during which time, at the tender age of 25, he won a personal commendation from the Secretary of the Navy. This was the first of many professional achievements that inflated the elder Malick’s ego — and lengthened the shadow under which his eldest son was born.

As Bleasdale writes, Emil had “a lifelong taste for publicity, and, in contrast to his son, self-promotion… even as a senior citizen, Emil occasionally telephoned the local newspaper, suggesting stories and sharing gossip, including news about his famous film director son.” The portrait that emerges of Malick Sr. from the biography is of a very vain, very brilliant man — a jet-engine expert, choirmaster, general macher — whose twin needs of achievement and recognition squeezed the life from his family and alienated his eldest son. Throughout his upbringing, Malick clashed heavily with his father, getting in many fights and disagreements. Finally, at age 12, he was shipped off to St. Stephen’s Episcopal School, in then-rural Austin; there, 100 miles from his father, his “delinquency,” as Bleasdale puts it, was quickly curbed.

His young adulthood was remarkable in the variety of his experiences. In his late teens and 20s, free of the paternal yoke, Malick pursued a sense of intellectual freedom that took him all over the world and into the highest echelons of culture. At Harvard, he proved himself such a gifted student of philosophy that Hannah Arendt, whom Malick met while studying at the Sorbonne, wrote him a letter of introduction to Martin Heidegger, the colossal German existentialist. At the tender age of 22, Malick visited Heidegger, whose work he’d read in the original German, and offered to translate his lecture, The Essence of Reasons, for Anglophone audiences; to this day, Malick’s remains its only English translation.

But apparently the strictures of academia were constraining to Malick, as were the demands of reporting, which he pursued after abandoning his master’s thesis. Although he seems to have enjoyed the sense of adventure inherent to journalism, he abandoned a plum assignment for The New Yorker on the trial of Regis Debray, and with it, his career as a freelancer. One imagines Malick more enchanted by the romanticism of Debray himself, of the marriage of ideas with the muddy realities of revolution, than the grinding work of the stringer, with its emphases on deadlines and narrative tidiness — elements he would struggle against in his subsequent creative career.

Filmmaking called to him as if on a lark, or by an accident called nepotism — a close friend of his from Harvard just so happened to be on the Admissions Committee of the American Film Institute. AFI was at that point a brand-new film school (itself a novelty), and the looseness of its mission, and the reputation of film as a bastardized art form — designed for cheap thrills and lurid stories — seems to have appealed to Malick’s sensibility. He began putting his friends in his student films, shorts about bandits and outlaws, in which he himself often played a starring role. From the start, his work placed a premium on looseness, naturalism, and spontaneity: the same values that had defined his life since leaving home.

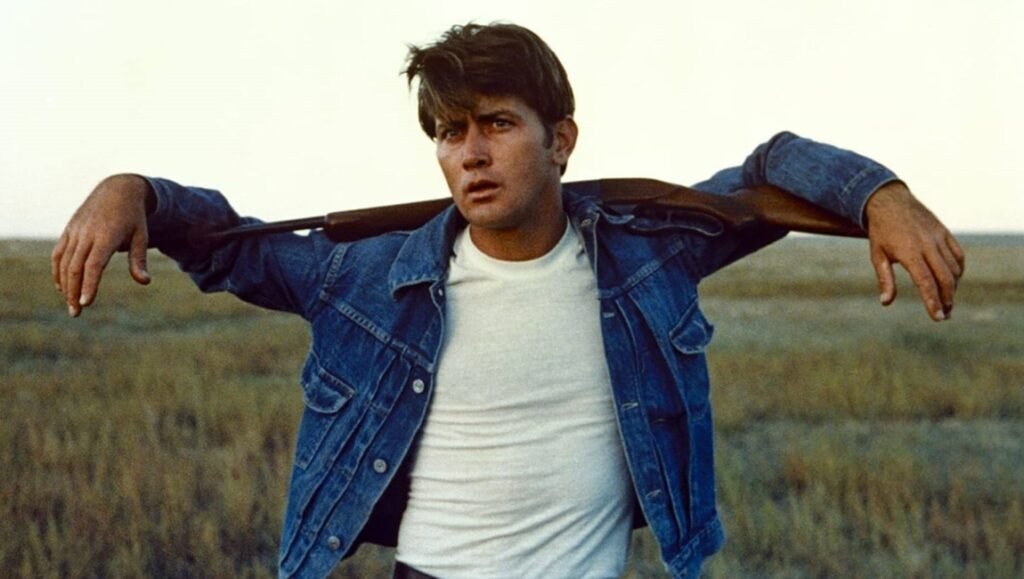

From the beginning of his directorial career, though, he also paid scrupulous attention to the costs of such freedom. Badlands, his first film, is a fictional treatment of the Starkweather-Fugate murder spree; in Malick’s hands, the story becomes a warped Genesis of the Flower Children, a parable of violence, the open road, and patricide. Kit and Holly, the characters played by Martin Sheen and Sissy Spacek, are unable to reconcile their lust for life with anything so dull as civilization; murder becomes a tool of solipsism, a way of eliminating any barrier to their desires. Ultimately, it’s Holly, Spacek’s character, who tires of their spree. “I felt all kind of things looking over the lights of Cheyenne,” she says in voiceover, “but most important, I made up my mind to never tag around with a hell-bent type, no matter how in love with him I was.” Kit gets the electric chair; Holly gets a lawyer.

In subject, if not in form, Badlands turns out to be a keystone for Malick’s body of work. Murder is obviously a transgression, but it’s also an act of self-definition, a monstrous assertion of self against a world of resistant others. A work of art is not dissimilar. It propounds a point of view that nobody asked for; in its content and form, it subjects, disarms, and transgresses. No coincidence that artists are among the first to be jailed under fascist regimes — in their expressive freedom, they represent a threat to order, to clean narratives of power. In light of Malick’s lifelong predilection for freedom and spontaneity, the links between the artist and the outlaw start to seem natural.

Beginning with his second feature, he shifted from making movies about transgressors to movies that themselves took transgressive liberties. With 1978’s Days of Heaven, he launched experiments with narrative form and editing that would flower, thirty-odd years later, in the Weightless Trilogy. A simple story of a love triangle becomes, in Malick’s hands, a kind of fugue state. We have a floating camera, untethered to the conventions of Hollywood cinema. We have narrative ellipses, leaps in the storytelling like gaps in teeth. There is the use of voiceover as counterpoint, complicating the exquisite images. Above all, there is a keen attention to nature, not only for its aesthetic beauty, but as a kind of oblique philosophical commentary on the drama.

Compare this to Song to Song, a film he made 39 years later, mostly on location around the SXSW Festival. There, too, we have a love triangle, between Rooney Mara’s waifish protagonist and Michael Fassbender and Ryan Gosling’s characters. All of the formal transgressions of Days of Heaven are taken to their logical extremes: a wild, roving camera, now digital and operated by Steadicam; the complete non-existence of exposition and narrative handholding; voiceover that skews toward obscurity, riddles; and as always, a Hegelian attention to light, to an Absolute beauty that pervades and exposes all things. Song to Song represents only a more aggressive form of a style — and of a personal sensibility — that had been forming over decades.

Like any experiment, the films of the Weightless Trilogy yield predictably mixed results. Some actors give themselves over to Malick’s method, like Michael Fassbender in Song to Song, while others look lost in it (see: everyone else in Song to Song). Malick’s increasingly spastic editing style can lead to a high-art sort of brain rot. He never holds long enough for us to get our bearings, to interpret images for ourselves, before cutting away to some other, striking shot. At times, he seems to want to break the visual grammar of cinema down to its constituent morphemes — shards of imagery and sound that achieve poetry in some instances and devolve into nonsense in others. I still don’t know why Nick Kroll shows up at a party midway through Knight of Cups, along with Ryan O’Neal and Fabio.

But I never sense, watching his Trilogy, that there’s anything less than a prodigious mind at work, an ethic of spontaneity that orchestrates and arranges even his most outlandish stunts. The biography sheds light on Malick’s unusual working methods, which place a high premium on looseness and creative freedom above all other considerations. Malick gave cameras for actors to operate, and their footage — shaky, nonprofessional — has sometimes ended up in the final film. Shooting scripts were written only to be abandoned. “Every morning,” Bleasdale writes, “Jack Fisk [production designer] offered Malick and his team a menu of possible locations for shooting. With a minimal crew and no lighting equipment, filming moved fast, and Widmer and Chivo [camera operator and cinematographer] shot constantly.” Post-production was just as unorthodox, with teams of editors working on specific parts of the movie or on footage of specific characters; only toward the very end of the process would Malick actually review the full cut. All of this breaks the rules of Hollywood production; the starry names in his casts (Brad Pitt, Ryan Gosling, Natalie Portman, et. al.) belie the intense art brut methodology.

These films have none of the stately polish of a work like The Thin Red Line — his comeback film from 1998, whose story is lifted from a classic novel and whose combat scenes were carefully storyboarded — let alone the grandeur of 2005’s The New World, which flirts with looseness and non-continuity, but which remains a handsome Hollywood epic. Part of this has to do with Malick’s change in source material. For the first time in his career, he set his narratives in contemporary America. Moreover, with his Trilogy, he mined the material of his own private life — his second marriage, his forays into Hollywood, and the creative ferment of his hometown, Austin — to tell highly personal stories in radical ways. He released five films in six years in the 2010s, an experimental spree that puts Starkweather to shame.

Predictably, mainstream critics piled on him like a squad of dull policemen. “His newer work reduces the elegant, layered storytelling of Badlands and Days of Heaven to simpler variations,” wrote Eric Kohn, of Indiewire. “What certainly began as a philosophical and aesthetic inquiry has wound up looking indulgent and shallow,” wrote Ann Hornaday, of The Washington Post. “Malick’s interest in creative freedom completely ignores the equally vital role of structure, rigor, and discipline, whether in the art of songwriting or filmmaking itself.” Time and again, Malick is subjected to a standard of narrative storytelling, of conventional Hollywood filmmaking, that he has clearly found constraining since at least the late ‘70s. He is punished for being himself and not the director that critics mistake him for.

The viciousness of the critical reception to these films also has something to do with Malick’s own silence about their making. He makes no effort to “get out in front of” these films, to try and promote a narrative of his intentions and influences like so many modern filmmakers do (think of Brady Corbet’s press tour for The Brutalist). These films premiere at major festivals whose red carpets he avoids. They drop quietly in local cinemas and have an equally muted afterlife on streaming. The elements of his unique style have become an opportunity for parody, simplification, and the sort of rote, cynical dismissal that thrives on the Internet. As it stands, Malick is in something worse than director jail — he’s in the zone of the irrelevant.

Which is a shame, because there are very few other contemporary directors who touch the places that he does — the numinous, contemplative, sorrowful areas that are the counterweight to the spirit of play in his work. At his best, his innovations in style accentuate moments of extreme emotionality. There are few jump cuts in cinema that hit harder than a certain cut toward the end of The New World. Pocahontas is lying in bed one moment, dying of tuberculosis, and seconds later, the bed is made, the woman has vanished, and her husband is left devastated. It’s a Godardian move, discontinuous and shattering, yet burnished in natural light and scored to Wagner of all things, and as I watched it again recently, after reading Bleasdale’s biography, I connected it to the history of loss the director himself had endured — suicides and premature deaths that I won’t go into in this essay. Suffice it to say, he has found uniquely cinematic expressions for private tragedies.

And perhaps it really is better to leave it at that. To be sure, the biography goes to great lengths to explicate his recent films, providing expository elements left over from their shooting scripts to fill in narrative gaps. Co-conspirators are likewise rounded up and interrogated, and the famous 20-year gap between Malick’s second and third film is demystified. I don’t know that any of this information is essential. It might even distract us from an appreciation of the work. Re-watching To The Wonder, Malick’s 2012 experiment, what strikes me now is how painful the movie is, how it functions as an aporia, a living testament to the “irreconcilable differences” that make up a divorce — what happens when two people love each other but can’t bear to co-exist. To know the details of Malick’s second marriage — the painful but often banal realities of his many years between Paris and Austin — is to gild the lily, and then press it behind glass.

But then this is the imperative of the biographer: to capture, to explain, even to resurrect. Bleasdale makes a noble effort to rescue Malick from irrelevance, arguing for the worthiness of not just the early masterpieces, but also the derided later films. Yet his biography also works at cross-purposes to an artist of uncommon restlessness, pinning him down with a narrative tidiness, a focus, that the artist himself has so long resisted in both his life and work. I myself am complicit in this. Despite my allergy to biographical readings, I’ve nevertheless used the biography in order to describe what I believe is a structuring principle of Malick’s life and work. This is a standard critical strategy. But it’s also, by definition, a reductive one.

I suspect that Malick is as indifferent to such taxonomies as any wild animal. At 81 years old, he remains burrowed in the editing room on his latest feature, a film about the life of Jesus. A story as old as time — but one hopes that in his hands, he’ll make it an oddity of epic proportions, something entirely new under the sun. In an industry marked by deep austerity and winner-take-all economics, he is in the enviable position to take risks — and remarkably, he’s taken them. “You are quite the individual,” a state trooper says to Kit, at the end of Badlands. “Think they’ll take that into consideration?” Kit replies, asking about his executioners. Malick is quite the individual — and as critics, as executioners, we ought to review the recent evidence, because here is an artist whose work refuses to die.

Comments are closed.