It’s mid-September, a broadcast TV network is on the brink of a merger, and an evening news segment could blow up these lucrative plans and send the network straight into a tedious lawsuit. A room of executives gather. They talk options. They discuss the risks of letting this man speak. They can’t afford it. They don’t want the trouble. It’s not good for their network. So they’re going to take him off the air. The first amendment isn’t on their minds, only their business.

This was 30 years ago, when CBS executives uttered the words “tortious interference” and decided to pull a 60 Minutes segment featuring former Brown & Williamson executive Jeffrey Wigand and his whistleblowing testimony that would reveal cigarette companies’ awareness — and manipulation — of their product’s addictive ingredients. But Jeffrey Wigand’s story starts in 1993, well before the Black Rock meeting described, and his initially reluctant efforts to blow the whistle, culminating in then-60 Minutes producer Lowell Bergman’s parallel efforts to get Wigand’s segment to air, are depicted in Michael Mann’s 1999 dialogue-driven thriller The Insider.

I fell in love with The Insider almost immediately, but it’s taken a handful of subsequent viewings for me to understand why this seemingly straightforward, ripped-from-the-headlines drama moved me far beyond its tightly plotted tension and Mann’s expected excellence — though yes, those qualities help, and The Insider is indeed pleasurable in its popcorn movie indulgences. Somehow, over the last couple of years, I’ve slowly stumbled into journalism. It’s been such a slow entry that I still feel uncomfortable using that “J” word, often opting for the umbrella term: “Writer.” And perhaps why I stutter describing any of my work as journalism is because I’ve hardly touched anything hard-hitting, and certainly nothing as brave as exposing corporate malfeasance.

I’ve rewatched The Insider three times this year, unintentionally revolving around what would become a 4,000-word piece about federal funding cuts to the NEA, NEH, and IMLS. It’s the hardest hitting, capital-J journalism that I’ve done. I spoke to over 30 sources. I had also just quit my day job in order to focus on my writing career (some would say, foolishly), and, because the outlet I wrote this for — the outlet that gave me my start as a journalist — was facing financial troubles and possible closure, I also (some would say, even more foolishly) wrote the funding-cut feature pro bono.

Within this same window, CBS and parent company Paramount were in a contentious, history-repeating, “tortious interference”-uttering conflict with the same Presidential administration I was writing about. By my first rewatch of The Insider, Paramount faced a possible lawsuit over a 60 Minutes segment. By my second rewatch, the lawsuit was moving forward, and Bill Owens had resigned from his position as executive producer of 60 Minutes in response to corporate decisions overriding the show’s independence. By my third rewatch, Paramount had settled the lawsuit, just closed its merger with Skydance, and CBS had cancelled Stephen Colbert’s late night show shortly after he criticized the settlement.

The Insider is one of those movies that could be called “prophetic” for how closely it resembles events that would take place decades later — nevermind that the movie is a retelling of past events. But if there is anything The Insider could foresee, it wasn’t the age-old story of Titans of Industry wielding power against whistleblowers, but the troubling limitations of journalism — and quite possibly all American systems allegedly designed to do good — to do no more than run by Industry’s playbook in order to sell information as a product.

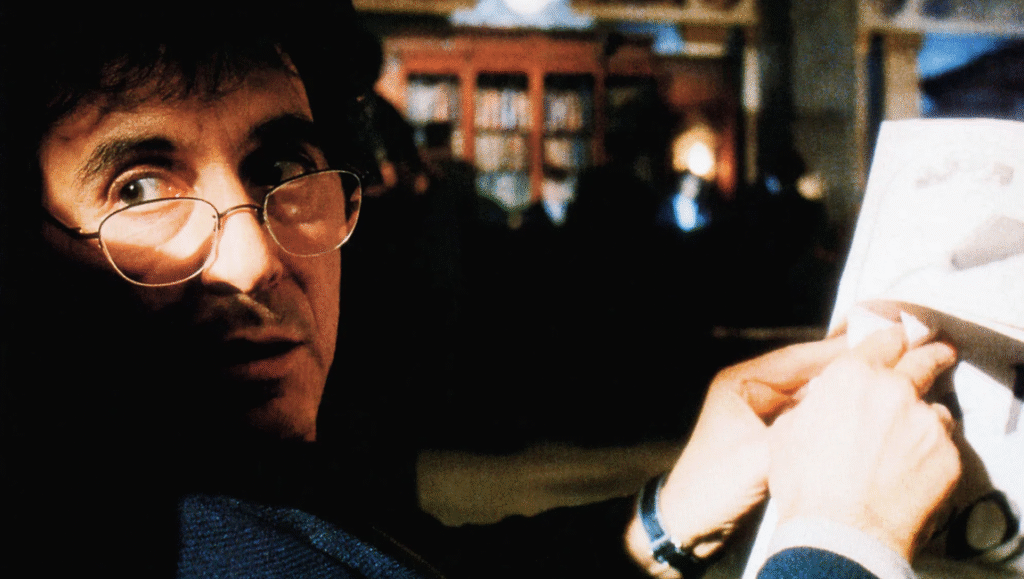

The first 40 seconds of The Insider keeps us in the dark. We can hear the quiet rumble of a car in motion against the short opening credits over black. The sounds keep us in anticipation with curiosity: Where are we? Where does this story begin? Who are we following? But the opening shot of The Insider does not satisfy these questions. We cut with an insurgence of the score to footage that is no more assuring than the text over black. We don’t immediately know it, but we are in Lowell Bergman’s point of view, and the wool is over our eyes. We sit with this shot for another 20 seconds as drums rhythmically crescendo. We can’t remove the cloth. We can only stare forward as glimpses of light pierce through its woven pattern. Only gradually do we become privy to the surroundings, though we continue to linger on Lowell’s shrouded face, alternating between his perspective and looking at him from the outside.

Our subsequent introduction to Bergman follows his work producing for 60 Minutes a rare interview with Hezbollah founder Sheikh Fadlallahh. This tight sequence gives us a firm impression of Bergman and his abilities as a journalist. He’s calm in the face of conflict and threatened violence. He’s diplomatic, never overstepping the boundaries of his sources, but working to meet them on their terms. Even as his vision is obscured, you sense him listening and observing his surroundings. His intuition and his resolve are strong. Once we observe the lead-up to the segment’s taping and Mike Wallace’s brash, opening line of questioning (“Are you a terrorist?”), we won’t return to this segment. Allegedly, we don’t need to. This is just another day for Lowell Bergman.

One of Michael Mann’s cinematic obsessions is the mirror image, in all of its abstractions. Literal mirrors, of course (abound in Manhunter), but other reflective surfaces — whether its men pondering in reflection over water or through windows, or the way some of his films interact with screens — and parallels drawn by a metaphorical mirror. It’s not an unusual tool for Mann, but it’s the entire core of his work in The Insider. After confirming to Wallace that the Hezbollah segment is on, Bergman looks out the window, finally taking in his surroundings, before we cut to Jeffrey Wigand, packing up his things inside Brown & Williamson, on the other side of a window in his office.

Bergman is excelling at his job — for now — and Wigand is sacked. That alone tells us quite a bit about these two men and the power dynamics that will drive the first half of the film; Bergman as the top-notch journalist who can handle a challenge, Wigand as a man in exile, separated from his celebrating coworkers, and watched ominously by security as he exits through the lobby and out a revolving glass door. Shortly after, Bergman’s family life is drawn against Wigand’s — the former’s is unconventional, but happy. The chaos is lived in. There’s warmth and easy conversation. Wigand’s family life, on the other hand, lacks such transparency. He has — but will lose — the picket fence, the family, and the propriety. Bergman is the hero journalist who will fight for Wigand, and while there is conflict between the two men, Bergman’s tenacity encourages Wigand to come forward, do what’s right, and seek justice.

But this is a Michael Mann film, and these seeming contrasts between the two men are far more parallel than we initially think. The shift in their dynamic begins at a dinner scene that plays off of the famous diner confrontation between Neil McCauley and Vincent Hanna in Heat. Wigand expresses his doubts to Bergman, insinuating that he’s just a product to generate news. In dialogue, Bergman holds his ground, pushing back on Jeffrey’s accusations and firmly standing by his integrity. Bergman is being honest when he says Jeffrey is protected, but it’s larger forces that will betray them both, and Mann conveys this with sneaky camerawork. As Jeffrey starts laying into Lowell, an almost identical shot of them seated in profile breaks the 180° line, putting Lowell in Jeffrey’s position; the hot seat at the left of the frame, where Wigand is also positioned in his 60 Minutes interview. Bergman’s positionality isn’t just shaken by Wigand’s paranoia, but by his suggestion that 60 Minutes isn’t in line with the radical journalism that gave Lowell his start.

Unlike, say, Heat, or Thief, or even Manhunter, Mann isn’t utilizing his trademarks to look at people struggling to get out of the bed they’ve made or navigating the interpersonal murkiness that blurs crime and punishment. The Insider turns outward, takes two men at a zenith of moral clarity, and asks if there is any system in the country, the world, or even the sovereign state of Mississippi that can rise to that occasion. If there is any question of whether Wigand or Bergman are seeing the consequences of their own actions, it’s less a question of denying their compromised ethics than it is their denial of a compromised system and its capacity to be changed from the inside.

The script is prime for showcasing Mann and co-writer Eric Roth at their most politically seething while also delivering on the quotability expected from the guy who made Heat. Skillfully, it keeps a pace where the audience is never allowed to sit in resolution; every problem solved is followed by a new hitch, keeping the two-and-a-half hour runtime brisk and unceasingly compelling. And while the odds stacked against Wigand and Bergman are Sisyphean in scope, the movie doesn’t withhold the catharsis of small (though largely rhetorical) victories — Bruce McGill’s cutting little courtroom monologue led by, “Boy, you got rights. And lefts. Ups and downs, and middles. So what?” easily brings the house down.

In 2025, it’s difficult to see journalism as more than rhetorical victories. The Insider navigates the undeniability that journalism is essential, but expresses skepticism that it will ever be enough. The trouble with journalism — and films about it — is that these instances either explicitly or incidentally are drawn as “extraordinary circumstances,” as Bergman describes. Even the groundbreaking Watergate investigation feels like it has had little bearing on the world today outside of becoming a branding convention for any remotely scandalous political fallout.

The movie is clever by contextualizing a world that exists past Wigand and Bergman’s experiences as whistleblowers. It’s easier to see these injustices as exceptional cases when divorced from anything else, but there’s always an O.J. Simpson headline or a reminder of the Unabomber at large, and the reminder that while Wigand’s story is the center of Bergman’s world, he does have other stories to cover. But most importantly, it uses Wigand’s story to contextualize Bergman’s. These are not extraordinary circumstances, but practices that occur every day through a cycle of breaking news and cover-ups. At the beginning, Wigand walks away from a company celebration and out a revolving door. At the end, Bergman does the same. His victory is a loss. “What did I win?” he asks his wife in defeat, even as Wigand’s segment finally makes it to air.

And cigarette companies survived. CBS meddles once again with 60 Minutes to protect a merger. Not too long ago, an expose revealed a culture of sexual harassment within CBS and 60 Minutes, overlapping with events depicted in this movie. We know these things now, but it is still more comfortable to think of them as extraordinary circumstances, though they continue, and they worsen. I am proud of my reporting on federal funding cuts and the stories I was able to tell that I now hold with me. But life has gone on. Newsrooms cut their staffs, I don’t know what the future of journalism looks like, and I wonder what it could ever possibly be but extraordinary stories — ones that must be told, yes, but what happens next? Who fights for these people long after they’ve taken incredible risks to speak out? It won’t be the systems, so then who?

The opening sequence of The Insider may be just another day in Lowell Bergman’s storied career as a journalist, but once we’re privy to the movie’s intentions, it plays differently. Bergman might be intuitive, but he is unable to see the people that populate Lebanon, the houses, the infrastructure, and the children watching as he passes. His view is limited, and that coolness in hostile environments may actually just be ignorance. He comes to this story with wool over his eyes, and journalism alone won’t help him see.

Comments are closed.