When you love a director, you have to trust them, there’s no other way. That’s not the message of Casino — a quasi-biblical text about the id at the core of the American dream — and it’s not necessarily a great belief to hold for an objective film critic, but it is a lesson you can glean by looking back at the reception to Martin Scorsese’s 1995 masterpiece and how it was misread by a critical hoard that was imprisoned by its moment. The film appeared to be an act of getting the band back together, a crime opera adapting a Nick Pileggi book starring Robert De Niro and Joe Pesci as a lilliputian psychopath. Coming five years after Scorsese had reframed his career with Goodfellas, many wrote about it as a longer, messier, more indulgent derivative of that classic. With the clarity of three decades now to separate the two works, it becomes clear Casino was a paean to scuzzy Vegas glamour and a poison pen condemnation of American excess, raising the stakes both figuratively and literally with more money, more violence, more color, more garish suits, more voiceover tangents, more needle drops, more everything in a film about the idea of “more.” It can now be seen as a crucial load-bearing column in the director’s filmography and mythology, Scorsese finding and refining both his style and what would be a career-long study of capitalism-fed ambition and how it corrupts the American soul.

Casino was odd for a Scorsese project. Not one of his one-for-them/for-hire jobs that he ended up wildly over-delivering on, nor a long gestating passion project, it was a rare convenience, a confluence of events that had a random, chaotic, slapdash feel in the moment. It began when post-The Age of Innocence Scorsese went back to the well of crime, first with a proposed adaptation of Richard Price’s totemic, humanist work set in the then unexplored world of the retail drug trade in North Jersey, Clockers. After spending some time with Price working on a treatment, Scorsese decided it was a story he wouldn’t be able to do justice to, and slid the project to Spike Lee. Instead, he returned to familiar terrain, with Goodfellas screenwriter, Nick Pileggi (or, Mr. Ephron), who was working on a book about a messy interpersonal and criminal catastrophe that fundamentally reshaped Las Vegas. The catch was that the manuscript wasn’t done, so Pileggi would spend months co-writing a screenplay with Scorsese holed up at the Drake Hotel in Chicago, then finishing the book (which as a result reads like a beat-by-beat novelization of the film in some sections) as principle production began in Vegas at an actual casino, the Riviera, during hours of operation.

You both do and don’t feel the on-the-fly nature of the Casino‘s constructions as a viewer. You don’t improvise a series of tracking shots, layered flashbacks, and masterfully blocked whip pans laying out the hierarchy of a gambling pit, but as is the case with so many Scorsese films, it was made in the edit suite with his work — and in many ways, life — partner Thelma Schoonmaker, and you occasionally feel the ramshackle stitching, but only in that Scorsese way that takes nothing away from your attention or the apparent quality of the product on screen. Casino would be the longest film Scorsese had made to date, one he famously described as plotless, and this shapelessness made for a rough edit as he and Schoonmaker tried to make sense of the footage.

The pair had a tall task, grounding a clear-eyed, sociological examination of Las Vegas under mob rule with a soapy love triangle starring De Niro as Ace Rothstein, based on the rise and fall of professional gambler-turned-casino executive Frank “Lefty” Rosenthal. At the peak of his powers, Rosenthal innovated the sportsbook and maintained an iron grip on the number of blueberries in each muffin in his capacity as boss of four entire casinos for a Midwest mob syndicate, before destroying the businesses, his marriage, and his remarkable opportunity. There wasn’t a firm sense of how this would all mesh, and in some ways it didn’t as seamlessly as Scorsese had intended initially. Notably, the first 40 minutes or so of the final cut, which lays out casino operations, had originally been scattered all over the film, but Schoonmaker and Scorsese realized it all needed to come in the first act so that the audience could fully comprehend the world and rules of engagement.

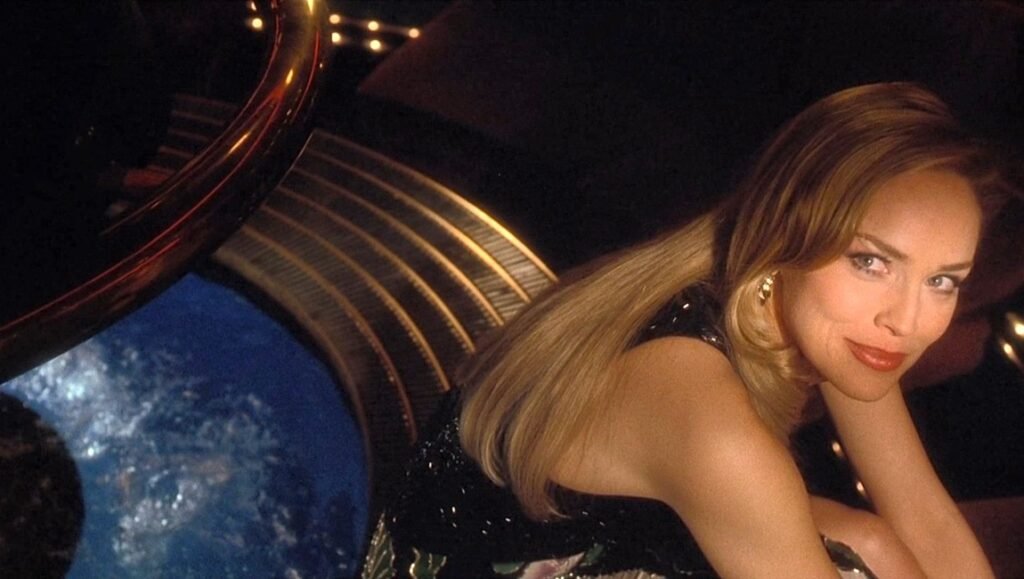

The film is shaggy but not really episodic in the way Goodfellas was, with a less defined traditional arc. Scorsese and Pileggi’s screenplay employs a light hand that glides into and out of the lives of two arrogant, heavy bettors who think odds don’t apply to them, on an alien planet dictated by rules that have their own internal logic. No one has a real “want” or “goal” to chart, to put it in Robert McKee’s traditionalist parlance. Sharon Stone fought for her role in Casino, describing working with Scorsese as a life dream and career ambition. She subsequently left it all on screen as the gorgeous and chaotic hustler Ginger McKenna — for which she received her lone Best Actress Academy Award nomination — and on set she spent a lot of time watching Scorsese’s process. She observed that the director doesn’t care as much about shot continuity as he does the emotional continuity from moment to moment, scene to scene, and before he made another sprawling epic about American grift that we’ll get to shortly, this was most true of Casino. Daniel Day-Lewis recently described Scorsese as “a sensualist who works like a coal miner,” and Casino might deliver the best exhibition of these two talents of Scorsese’s maximized. Because of its shapelessness and length, it’s a movie in which Scorsese’s propulsive style can’t be dismissed by even his most ardent detractors as flourishes of excess, as the film needs every camera glide and needle drop to make the three chaotic hours feel bloat-free, like a much shorter film. Not every critic at the time (and even a few, though significantly less, now) agreed that he’d accomplished that.

Derek Malcolm’s mixed review in The Guardian opens, “Those expecting the passion of Raging Bull or the unorthodox, quirky brilliance of The King Of Comedy may well be disappointed with Casino,” and closes with, “In a way, it’s like a symphony you have heard before but can’t quite remember when,” insulting the film with faint praise, as an exercise of Scorsese’s breathtaking style over substance. Entertainment Weekly graded it a mediocre B-. SFGATE went full Shalit with the headline “SCORSESE’S CASINO COMES UP BROKE/STONE’S THE ONLY ACE IN A BAD HAND.” In Newsweek, David Ansen opted for an oft-repeated angle, breaking the film into halves, praising the procedural/anthropological Vegas elements while deeming the human drama “stillborn” and once again accusing the master of repeating himself: “It doesn’t help that [Scorsese has] been to this wiseguy well once too often. The sense of discovery, and the shock value, are gone.” Based on its sure-thing equation of Scorsese + De Niro + Pesci + Crime, the film made money, $116 million on a budget ballparked between $40-50 million, which was good for fifth, opening behind Toy Story on a historic Thanksgiving weekend. But Sharon Stone received the film’s lone aforementioned Oscar nomination, and with critical response vs. expectations dominating the discourse around the film, Casino was viewed as a slight letdown at best.

Nearly every critic included the context of Casino and where it fits into Scorsese’s career, particularly relative to Goodfellas, but few got it right. As opposed to a Goodfellas sequel (the popular read, now viewed as the second installment of a trilogy that ends with The Irishman), Pileggi saw the film as the final installment in a trilogy, one that traced the layer cake of the American mob from entry-level, fuck-up kids at the bottom in Mean Streets, to the middle class scammers, strivers, and schmucks in Goodfellas, to the bosses of the bosses at the elite tiers of national wealth and power in Casino. Today, you can go in a few directions if you’re interested in contextualizing Casino within Scorsese’s massive, near perfect, and now near complete body of work. It can now be seen as a midpoint in a crime pentalogy that also includes Gangs of New York. But it can probably be best understood in its themes and presentation as a kind of spiritual prequel to 2013’s three-hour long, voiceover-heavy, scotch tape-edited, profane, alluring, grotesque, and coke-addled The Wolf of Wall Street, another process-rich anthropological study of the crooks practicing morally bankrupt legalized American extortion, made nearly two decades later.

“[Casino is] about greed and how it can destroy. Marty wanted to make a statement about what America was doing to itself and continues to do to itself… how this shallow culture was going to be a problem for America,” Thelma Schoonmaker says. In Sam Rothstein, Scorsese follows Lucifer kicked out of heaven for his pride, a character whose arc mirrors the hubris, avarice, self-delusion, and eventual self-destruction of the mob’s brief control of Vegas, a manifest destiny in miniature. In an era of gentiles being cast as Jewish, Robert De Niro as Sam Rothstein is still one of the more hilarious stretches that Jews and people who know them have been asked to accept, but Ace’s Jewishness is core to the film. In Chicago, Rothstein, the refugee professional gambler on the run from the law, becomes a pillar of society in Las Vegas for the exact same set of skills. The irony isn’t lost on him: “Anywhere else I’d be arrested for what I’m doing. Here they’re giving me awards,” Ace says.

The Jew has found a way to assimilate into the upper crust of WASP society because he’s found an acceptable business once dismissed as a vice, until prim Protestant morality lapses at the recognition of how lucrative that vice can be. It’s a parallel trajectory to how the Jewish Vaudeville barons ended up building the Hollywood studio system: they snuck in through the backdoor. His gangster friend from home, Nicky Santoro (Pesci), tries to explain this to Ace, that he’s a placeholder and an errand boy in polite Vegas society, that Nicky’s muscle and the “Gods,” or mob bosses behind him, are the only things keeping a rabid pack of wolves from picking Rothstein’s “Jew ass” clean and ejecting him from his desert palace, but Ace can’t hear him. The gladhanders and showgirls smiling in his face for as long as the check clears are fleeting surface bullshit; for all his brilliance and efficiency they see Ace as a useful idiot. It’s Nicky, taking Vegas by force, understanding it as a lawless realm of wanton criminality, who sees Ace for who he is because they grew up together. He respects Ace for what he can do, and in doing so, Nicky is something, someone who is real, if not exactly a friend, but Ace chooses fidelity to the dream, the lie that if you make yourself useful to the conventional American power structures, they’ll accept you and you can keep the way out of the league shiksa bombshell you paid for.

“It’s Vegas at the end of its heyday. It was almost like the end of the Wild West, the end of the frontier towns in the 1880s,” Scorsese said of his attraction to the story. His Vegas is a church of excess, a perfect laboratory for Scorsese’s theological inquisition: how much is enough? The answer is accumulation, a poverty of philosophy. If “more” is your God, you have created a hole of need that can’t be satisfied. The only logical conclusion is eventually fucking up a good thing. Scorsese imagined Casino as a Western centered around a gunslinger, a showgirl, and a bean counter, on the bleeding edge of civilization in the midst of a gold rush, falling prey to deeply human greed and savagery. The mob went West and brought unchecked capitalism with them to this shitheel desert town and these people they looked down on. It was land that was taken forcefully by criminals committing an act of opportunistic barbarism Scorsese would revisit in Killers of the Flower Moon set during the chaotic and semi-lawless Osage County oil boom, before the government would step in and formalize and legalize the criminality. “The genre of the underworld, the closest it comes to the overworld is in Vegas,” Scorsese said.

There are many indelible images in the film: Saul Bass’ opening of a pastel-suited figure tumbling into the neon pit of Hell; the sequined Goddess raining lavender chips upon the huddled masses; the head in a vice turned until an eye squeezes out; the bat-beaten brothers, bloodied and slowly being buried alive in a single grave dug in the middle of a cornfield. But for this writer, the standout is a shoulder-to-shoulder nightmare army of backlit, smudgy silhouettes only discernible enough to tell they are geriatrics on a death march toward the slots, the image arriving over the strains of “St Matthew Passion.” It’s one of Scorsese’s most Lynchian shots, each shadow figure en route to torture Naomi Watts to death.

For the millennial, our entire lives have been spent understanding Vegas as a den of iniquity, but one that offers four-quadrant entertainments. Casino explains that this wasn’t always the case, that the strip was a deviant seedy place for deviant seedy people, an actual pirate ship, not a ride in a theme park attached to a gambling floor you could drop the kids off at while you go shoot craps. Scorsese casts this sanitization as nefarious. Converting Vegas from a capital city for the hustlers and degenerates who understood the rules of the Never-Never Land they’re playing in, to attacking the once nuclear core of America, the family unit, is the true criminal enterprise he waits until the end to disgust us with.

Casino is a chronicling of the depths, the depravity people will commit in the name of the deeply American conviction that every problem can be solved via capitalism with wealth — with the shit or people you can buy. But Scorsese clearly believes human nature makes this a rigged game, and over 30 years in this country, he has defied his critics from that time, as his message becomes more potent by the day and his film has been reclaimed as a masterpiece. “Recently there’s been a spread of new casinos all around America, which reflects desperation, when people think that with one throw of the dice their whole life will be changed,” Scorsese has said. “But it’s never enough, til’ everything explodes and comes down.”

Comments are closed.