Over the weekend of November 14-16, I viewed the entirety of Twin Peaks: The Return, screened thanks to the great efforts of the Philadelphia Film Society. Parts 1-4 were shown Friday night, parts 5-11 on Saturday, and parts 12-18 on Sunday. It was, perhaps needless to say, a strange crew of people that attended, among which I include myself. Enthusiasts, fans, academics, graduate students, basement dwellers, culture hounds, cinema fiends, people driven by a bizarre desire to watch 18 hours of a notoriously dense and off-putting epic, which requires for basic comprehension the viewing of the original two seasons of Twin Peaks, plus the film Fire Walk With Me, and its companion, FWWM: The Missing Pieces, let alone the printed works of Laura Palmer’s diary, and two books by David Lynch’s co-creator and co-writer — The Secret History of Twin Peaks and Twin Peaks: The Final Dossier. This grand buildup indicates the most remarkable aspect of The Return, the very fact that it exists, that it was able to come together from out of the weight of the past, with the same cast, and all directed by the master vision of Lynch.

The late director’s spiritual and metaphysical mode is classically gnostic and Manichaean, rife with secrets and hidden agendas, which seem to require deep inquiry and meditation in order to even begin to understand. The esoterica of Lynch’s work is often the drawing point for viewers, as they attempt to interpret and analyze, to catch the references and weave them together into something meaningful, a puzzle box to be solved. Yet this impulse is the wrong one. In a chronological sense, Lynch’s works do not make sense, but in an emotional one, they are perfectly clear and obvious. Time may not progress as we understand it, but the emotions never lie. Lynch has a romantic sensibility, and he never tricks his viewers. There is not an ounce of cynicism in what he showed us.

In The Return, we have the great work of American moving image gnostic tragedy, a late imperial artifact of an age of crisis. The plot is simple enough — an agent of good attempts to save a girl, but he does not succeed. The tagline of Lynch’s last film, Inland Empire, or at least his last work that fits within the boundaries of what we currently define as film, serves as the epitaph of his entire body of work: “A woman in trouble.” Tellingly, this does not indicate if she ever gets out of it. In the murder of a single girl is contained the entire struggle for the fate of humanity. As above, so below. This is not mere humanism. For Lynch, we are each of us engaged in spiritual warfare, whether we know it or not, perhaps especially so if we do not. The overall effect of Lynch should produce an unbearable cringiness; all the elements point to it. But this initial aesthetic impulse is undermined by Lynch’s absolute moral seriousness. Yes, everything is absurd, things don’t make sense. But, a girl is dead. A woman is in trouble. This is no laughing matter. Your soul is on the line. Lynch’s mythology is dense, but the core of it, the truth around which the entire mechanism orbits, is crystal clear. The sexual abuse of women is the foundational act of our society, repeated again and again. Laura Palmer is there, in every headline of rape and murder and disappearance. She has always been there.

Lynch’s world is divided between good and evil, with the vast swath of humanity caught between these forces, but this is no fairy tale. It is too much to say that evil wins in The Return, but it is certain that good does not triumph, which is a very different thing. Evil is simultaneously an alien and yet intimate force in Lynch’s world. It cleaves to those closest to us yet comes from beyond a plane of our comprehension. In Part 8, a monstrous creature that appears to be a combination of a rabbit, frog, and cockroach hatches from an egg buried in the sand of the Trinity atomic test site. At the end of Part 8, it slides into a girl’s mouth, with the implication that this girl will grow up to become Sarah Palmer. Evil may come from outside, but it burrows within us, and lives on, imbricated with our reality. Similarly, in the opening sequence of Blue Velvet, shots of a white picket fence and a charming, wholesome suburb rapidly transition to a man collapsing, before tracking down onto the grass of a front lawn to show insects and beetles crawling beneath. To modify the famous May ’68 slogan of “Sous les pavés, la plage [beneath the pavement, the beach],” for Lynch, the meaning is reversed. This is an anti-utopian vision, that beneath our beautiful reality, something dark and malignant grows. Beneath the grass, the decay. In the original run of Twin Peaks, the specter of patriarchal abuse and rape within the nuclear family was the primary evil. In The Return, the specter now is maternal abuse, Sarah Palmer, a bewitched entity, drinking herself to oblivion in front of a time-looped TV that shows scenes of boxing and lion predation, the potential and fallout of violence coursing through her like a current. Fathers can kill, maim, destroy, but only mothers can curse entire generations. His is the ultimate feminist vision, in a morbid sense — cosmic evil can be female too.

When I think of Lynch, I think of Menocchio, a 16th-century miller chronicled by the historian Carlo Ginzburg in his book The Cheese and the Worms. Menocchio crafted an individual theory of the universe out of the detritus of the then-new technology of the printed word, collecting books and pamphlets, and, in his half-learned and literate abilities, synthesizing them together to create a world both distant and familiar. Lynch, a child of the moving image, did the same with the current comparatively new technology of film. Lynch took scraps and pieces from the Golden Age of Hollywood, the matinees and TV marathons of Cold War America, echoes of familiar genres and celluloid mythologies, and re-worked them, mapped them out on the terrain of his own fears and hopes, and created a universe uniquely his own, made more uncanny to us by its familiarity, like unexpectedly meeting an old friend on the other side of the world, but the friend does not recognize us. This mapping of Lynch, this molding of the familiar along personalist lines into something new, is what separated him from mere pastiche or genre exercise. Lynch did not seek to emulate, follow, replicate, or transplant. He did not translate filmic language, he was not a scholarly expert or enthusiast of it, as with a directorial type best exemplified by Del Toro and Tarantino. Lynch spoke film, and in doing so created his own language. The words are familiar, but the meanings are shifted. We recognize elements of the noir in almost everything he made, but he is not reducible to such. The classic Hitchcockian psychosexual dynamic of the blonde vs. brunette woman is elevated by Lynch into a metaphysical principle, but also transcends it. The Return contains slapstick and screwball to outdo the canonical films of Hawks, before shifting into horrific, nausea-inducing violence, but it is not a work of action. Elements of meta-commentary and post-modernism are shot through it, like veins of a precious metal within a mountain. Doppelgängers, tulpas, false selves, switching, doubling, are rife throughout, not merely on the basic level of the good/bad Cooper, but even The Return itself as a kind of tulpa of the original run of Twin Peaks, a universe come back to life after a quarter century, in which the form is familiar, but the heart is a stranger.

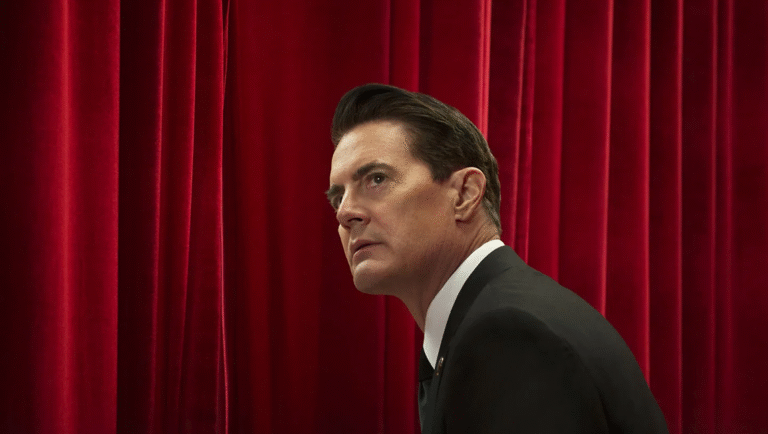

Lynch’s ambient dreamscape is that of the 1950s, reflected in his own boyish, wholesomely eccentric persona: the slick-backed hair, the smoking, the coffee drinking, the love of diners, his ladies’ man, no kiss-and-tell gentlemanly heterosexuality. It’s a child’s idea of a cool guy, a child raised in the 1950s, which Lynch was. Lynch’s registers follow the ’50s logic; Cooper’s doppelgänger wears a leather jacket to signal his darkness, our hero is an FBI agent. When Agent Cooper triumphantly declares the line, “I am the FBI,” in part 16, which caused the theater to erupt in cheers and applause, we are in the territory of early Cold War TV cops and robbers, dime-store comics. Yet, the shocking explosion of part 8 also channels the atomic fears of that benighted decade. I imagine Lynch as a child, taking part in an elementary school duck-and-cover exercise, knees drawn up and trembling under his desk, contemplating in his youthful wisdom the possibility of the end of the world in a radiated holocaust. Was it there, in that darkness below the surface, eyes shut, that he first began to formulate his mythologies? In The Return, the 1950s have expanded into a never-ending totality, a failed present, while the testing of the atomic bomb has become a portal for the transmission of a cosmic, time-warping, unnamable evil into our world. Cold War America has swallowed the world, and we are drowning in its belly.

As a boy myself growing up in the rural American West, I often saw electrical transmission towers on the seemingly never-ending drives I took with my mother as she ran errands. They rose up on the horizon, strange mutant steel giants. I often imagined the towers would one day walk and march across the desert. Lynch is the only filmmaker I know of who has accurately channeled the sense of foreboding I felt as a boy gazing upon those towers. The American West was conquered, and waves of Native peoples murdered and ethnically cleansed so that these towers and their electrical lines could be built. Each is a testament to a land soiled in blood. They had to be built so that the force of electricity could run across the length and breadth of the continent, so that America could stretch out and become a superpower. Is it any wonder that Lynch in The Return links electrical transmission as the spiritual conduit for otherworldly spirits and negative entities? The hum you hear next to these towers is one that signals death. In The Return, constant driving is a motif. Characters must drive vast distances across the American West, the attempt to get from point A to point B forming the backdrop to the action. There is movement from Las Vegas, to Texas, to South Dakota, to finally to northern Washington state. This is a region of emptiness, filled only with highways and electrical lines, terraformed into agricultural zones, the rivers dammed and rerouted, reservoirs built, the physical landscape re-shaped to fit the needs of settlement and expansion. Spirits haunt this land, they race through the electrical lines. It’s easy to get lost out there, in all senses.

The Return is neither TV nor film in a strict sense, but something else altogether. While it is serialized, it does not follow any standard logic of TV progression, no character and plot development that can be neatly charted out. It is neither a miniseries nor a one-season story. For a film, it is too long, too sprawling, defying the bounds of theatrical structures. While Cahiers du Cinéma categorized it as film for lack of any other option, its ultimate form is singular. The closest comparison to The Return is the great Soviet 1960s epic film adaptation directed by Sergei Bondarchuk of War and Peace. Made with essentially an unlimited budget, making use of tens of thousands of extras and a level of historical authenticity and scale the logistics of which rival the feats of the Napoleonic Wars themselves, which it depicts, it exists outside of the usual understanding of what moving image art is. No other such film will ever be made again, as no authoritarian state such as the Soviet Union will ever exist again that both can and is willing to mobilize resources on such a scale. Bondarchuk’s work breaks the boundaries of cinematic possibility in the same way that The Return does, but from the opposite end — The Return is a work of hyper-individualism; not a national epic, but a private mythology, created through a decades-long obsession and maniacal attention to detail and trust in one’s own instincts and vision. The Return is American creative individualism and the myth of the Great Artist most truly exemplified, just as the 1960s War and Peace is Soviet technical expertise and national mobilization most truly exemplified. Moving image artistic achievements that highlight the greatest their respective nations had to offer, the likes of which shall never be seen again. The Soviet Union collapsed 20 years after War and Peace was completed. Where will America be in 2037?

Lynch never insulted his viewers’ intelligence, but he did love to play pranks on them. Take the character introduced in part 14, and who defeats BOB in part 17, Freddie Sykes — Lynch laughably provides a neat and simple resolution, inserting an over-the-top deus ex machina device in the form of a British lad given access to a super-powered latex glove and spiritually guided to Twin Peaks. The jokes on TV as a form, resolution as an expectation, exposition as the laziest vice: well, they write themselves. But then Lynch pulls the rug on us in Part 18, as we are thrown back into the uncanny, and the unknowable proves victorious. It was never going to be that simple. From the beginning, Lynch also makes fun of our attempts to understand. In the first part, a young man sits on a couch and watches an empty glass box, with multiple cameras trained on it, endlessly recording, paid to look for something, anything, which might occur within. In the end of the first part, that young man and his lover have their heads ripped off by an unknown entity beamed into our universe through the glass box. Has there ever been a more cutting metaphor for the futile act of engagement with the moving image? And perhaps this is Lynch’s warning to the viewer, the message given at the beginning; if you keep looking for something here, if you keep digging for meaning, don’t be surprised if something happens to you. It’s dangerous to look too deeply. And maybe this very medium of the moving image is doing something to us, is doing something to you. Maybe evil, or at least forces beyond our understanding, are lurking there, just past the screen, just beyond the barrier of the light projected onto it.

The act of watching the glass box, watching the screen, it reminds me of the scrying practices of the early modern era. A man sitting behind me commented right before part 18 began, “They’ve lost the plot.” He was right. The Return ends with the sense that the story we thought we were seeing, the emotional meaning we thought we had comprehended, has gone away. Something has shifted, we’re lost again, we’re back on the road from Odessa, Texas, to Twin Peaks. An attempt to change the past has scrambled reality. We don’t know where we are, and our characters don’t know who they are. When the actual moment of true return occurs, a woman who seems to be Laura Palmer standing in front of her childhood home, the horror sets in. We’ve become lost, we don’t know the year. A shattering scream, glass breaking, then darkness. There is no better political statement on America of the last decade. Things are winding down, everyone wants to turn back the clock. Visions of postwar prosperity are held up to emulate, but we all know we can never truly go back. Our president is old and sells gold and malevolent kitsch on TV. The sense of the future is gone as well. History has not so much ended as it has disappeared. What year is this? I don’t know, and I don’t think anyone else does either.

Lynch shows the town of Twin Peaks 25 years on as being in a state of advanced decay. In interludes in the parts, in which we linger on the people gathered in The Roadhouse, a kind of purgatorial zone or bardo, between the musical sets, people discuss their lives. These figures, barely rising to the status of side characters, fulfilling more properly the role of a chorus as in ancient Greek theater, express the darkness. Their lives are filled with inexplicable acts of violence, drug use is rampant, everyone is unhappy with their sexual and romantic interests. Jacques Renault, the Quebecois owner of The Roadhouse, who was directly involved in sex trafficking, prostitution, pedophilia, and organized crime in the original two seasons of Twin Peaks, is still there, still running the bar, and still trafficking girls. The daughter of Shelly and Bobby is married to a drug addict and lives in a trailer park. The lives of the trailer park residents are marred by poverty and hopelessness. One resident sells his blood to try to make rent money. Things never got better — they got worse.

Before the last part screened, the programmer of the PFS suggested that we all get together in front of the screen when it was over and take a group photo for posterity. This did not happen. People rose slowly and solemnly from their seats as the credits rolled, downcast eyes. No one talked. The weight of what we had just seen was oppressive. This was no occasion for commemoration. A photo felt like a sacrilege. Laura Palmer’s scream echoed within that silence. It is echoing still.

Comments are closed.