My introduction to Bob Clark came through his latter holiday comedy, A Christmas Story, a film I grew up with and still associate with seasonal nostalgia. Only in adulthood did I learn that he also directed a ‘70s horror film saturated with Christmas imagery. It’s not what people usually have in mind when they think of Christmas movies, which is precisely why it’s the one I now recommend most. Often labelled a proto-slasher, Black Christmas (1974) predates the genre’s framework, a formula later cemented by John Carpenter’s Halloween in 1978. It helps establish several conventions that would come to define slashers — the killer’s point of view, the confined domestic setting, an early version of the final girl — while most distinctively popularizing the threatening phone call, a device later adopted by When a Stranger Calls and reworked into pop iconography by Scream.

Black Christmas is set primarily in a sorority house and punctuated by point-of-view shots in the attic’s tight quarters, which lends the additional aura of claustrophobia. Clark’s film first deceptively introduces us to the Yuletide-adorned residence, with Christmas carols crooning over the opening credits, but trepidation underlies the shot through the camera’s subtle wobbliness and the foreboding that envelops the sorority walls. As we move closer to the house, the shakiness of the camera intensifies, and obscene heavy breathing permeates the space, as the once neutral sequence reveals itself to be from an unknown observer’s perspective, the figure later recognized as Billy.

The film fully leans into classic Christmastime tropes, aesthetically and thematically. Warm color grading and vibrant lights of the decor evoke feelings of holiday comfort. And as we transition indoors, the residence is filled with loved ones celebrating. Even amid the escalating horror, that sense of comfort never fully dissipates because of the characters’ interpersonal relationships and the small humorous moments that sustain them. Despite that, the film subverts the holiday genre by fusing it with what would later become hallmarks of the slasher. Harassment, violence, femicide, and institutional incompetence terrorize the women of Pi Kappa Sigma, shattering the artificial warmth of Christmas in favor of winter’s natural chill and darkness.

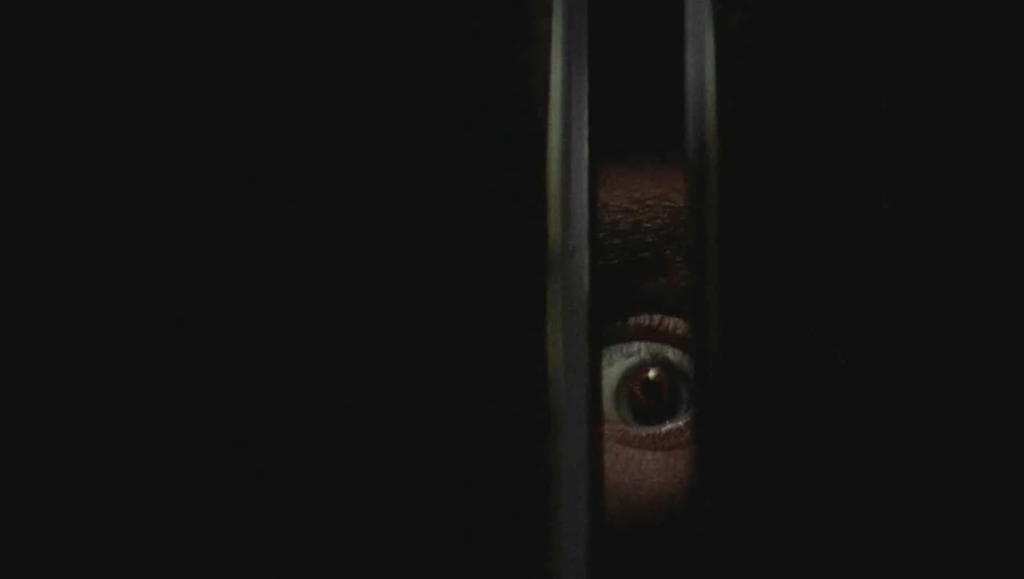

The film maintains a delicate balance between what is shown and what is kept to the audience’s imagination, creating unease that functions as an abstraction of the killer, Billy, who lurks behind doors, in the shadows, or up in the attic. Whether or not we discern signs of him, that unshakeable eeriness is a signal of his constant presence. The most we ever see of Billy occurs an hour into the film when he murders Barb (Margot Kidder). His face is obscured by a shadow, but the outline of his hair and visage is visible, with one eye illuminated by a micro spotlight. Visual access to the killer stays restricted, but the camera repeatedly positions the viewer within his point of view, fostering a paradoxical tension of detachment and unsettling intimacy. Disembodied sound sharpens the threat Billy poses through intrusive sexual phone calls, perverse labored breathing, and a variety of voices that violate the house from within, rendering his presence inescapable even when he remains unseen. But even with more sensory access, we are still in the dark. This restraint is what makes Black Christmas so effective, because it refuses to succumb to any limitations that would have been imposed if Billy were given a stable identity, psychology, or backstory. The film trusts that what its audience members individually conjure will be more potent than anything concrete it could show on screen. The choice to withhold transforms absence into a source of fear, prompting the audience to fill in the gaps by drawing on both their personal anxieties and those that reflect their sociopolitical landscape.

The ambiguity surrounding our killer pushes us toward a more tangibly identified villain. Jess (Olivia Hussey) divulges the news about her pregnancy and desire to have an abortion, while her boyfriend Peter (Keir Dullea) rejects her guilt-free choice as she refuses to abandon the future she had envisioned for herself. Peter’s waning power over her autonomy makes him irate, persistent, and violent, and he destroys a piano at the conservatory in an angry fit. Both Peter and Billy are figures of male rage. Peter’s aggression and misogynistic control operate alongside Billy’s linguistic and physical violence as complementary expressions of the same threat. The viewers’ lack of information about the killer allows Peter to become an easy stand-in for Billy, as the glimpses we do receive align with Peter’s visible presence as a white man with a medium-length shag. This deflection of suspicion is reinforced narratively through explicit clues, most notably Billy’s repetition of things Peter said to Jess during a private argument regarding the abortion, all of which render Peter a convincing red herring.

The film’s misogyny is not confined to Peter or Billy, but is also embedded in the systems meant to protect victims. The local police department initially dismisses reports of the first disappearance at the sorority — Clare Harrison (Lynne Griffin) — assuming she is with her boyfriend because that’s the case “90% of the time [for] girls who are reported missing from the college.” They do not take any concerns seriously until her boyfriend, Chris (Art Hindle), goes to the station and urges them to investigate. While Clare’s fate was sealed before she was even deemed missing by her father, the police’s delayed reaction and subsequent incompetence sealed the fate of the women who came after her. This pattern of negligence compounds as the investigation progresses. Once Peter is identified as a suspect, the police misallocate their vigilance toward him, allowing Billy to continue murdering from the shadows. When an officer calls Jess to instruct her to leave the residence, he sends her into a panic by prematurely disclosing that the caller is in the house while attempting to suppress inquiry, compromising her chance to escape before Billy goes after her. Treating Peter’s death as closure, the police forgo a full procedural sweep of the house, leaving Billy in the attic with the bodies of Clare and Mrs. Mac (Marian Waldman). The same officer who fumbled the warning call to Jess is assigned to keep watch over her, but once again his negligence resurfaces as he steps outside while she remains unattended, a final call ringing into the final credits.

The same restraint that defines the film’s killer also governs its depiction of physical violence. Like Billy, it is frequently withheld from view and largely experienced through its aftermath. The violence itself is also gendered: all perpetrators are men and all victims are women. Barb’s murder, for instance, is presented through the actions performed on her, with its consequences shown after the violence has passed. Our access is limited through sound and fragmented images, including the glass unicorn used to stab her to death, one of the film’s few moments of explicitly phallic brutality. Yet the restraint does not diminish the horror of the scene, in which Barb is killed while Jess listens to a group of children perform Christmas carols at the front door. The dissonance between the innocence of the children singing over the corruption of Barb’s life is a disturbing portrayal of violence that circumvents spectacle. Similar to the audience, Jess encounters the violence after it has already occurred, when she later finds Barb’s body alongside Phyl (Andrea Martin), whose murder transpired completely offscreen.

Released over a year after Roe v. Wade, Black Christmas taps into societal anxieties surrounding women’s bodily autonomy, from people who wanted to deny them that control to women themselves who had to navigate this newfound freedom while confronting those who believed they shouldn’t have it. In 1974, viewers watched with Roe as a backdrop in their own lives but without much additional codified protection for women. It took North America nearly 20 years to criminalize stalking, a crime that disproportionately affects women and one the film stages through Billy’s calls and ongoing surveillance. Women’s fears were visible to them but structurally unseen by the institutions meant to protect them, a dynamic that remains largely unchanged. Over 50 years later, Roe v. Wade has been overturned, and misogyny, encroachments on our bodies, and blatant negligence in our police and justice systems are still prevalent fears. Any sense of historical distance has collapsed, lending Black Christmas a renewed horror rooted in the persistence of these same vulnerabilities.

Comments are closed.