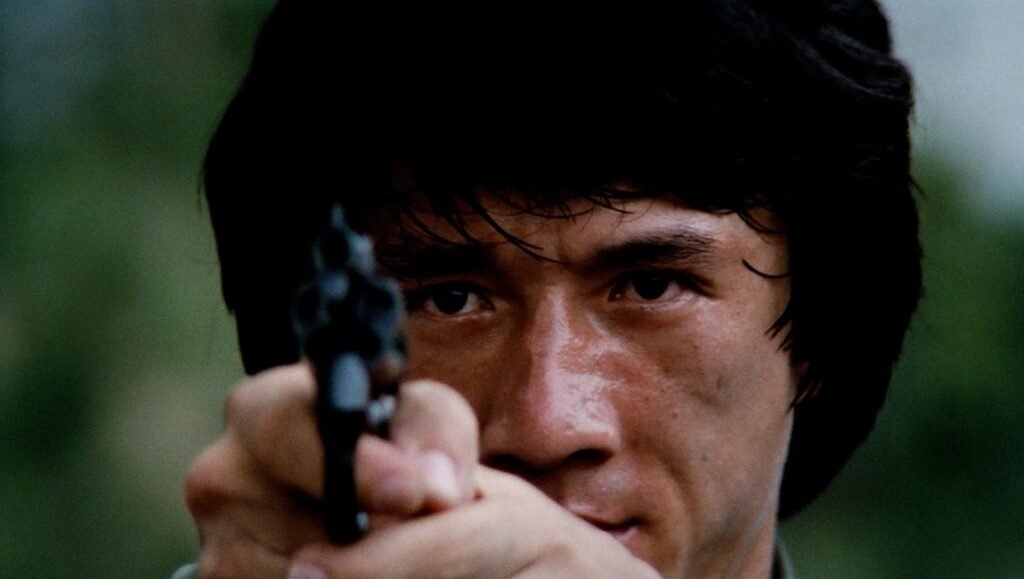

As the economic and political importance of Hong Kong expanded exponentially in the second half of the 20th century, so did the reach of its cinema. And no one embodies this success more than Jackie Chan, the face of Hong Kong cinema exported all around the world. His promise was clear from early on, and the production company Golden Harvest invested accordingly. In 1980, when they let him direct for the first time with The Young Master, his comedic, kinetic, and vulnerable sensibilities synthesized into a recognizable form. Cinema changed. From roughly 1980 to even more roughly 1995, he would go on an incredible run of action-comedies that would enshrine his talents in film history: Wheels on Meals (1984), Police Story 3: Super Cop (1992), Drunken Master II (1995), Rumble in the Bronx (1995), etc. The list doesn’t really end. He is an auteur for the masses, the greatest action star in the history of the silver screen, and arguably our greatest global entertainer. Very few things on this planet bring as much joy as watching Jackie Chan do Jackie Chan things at his prime. And 1985’s Police Story, now 41 years old, is damn close to the summit of that incredible prime.

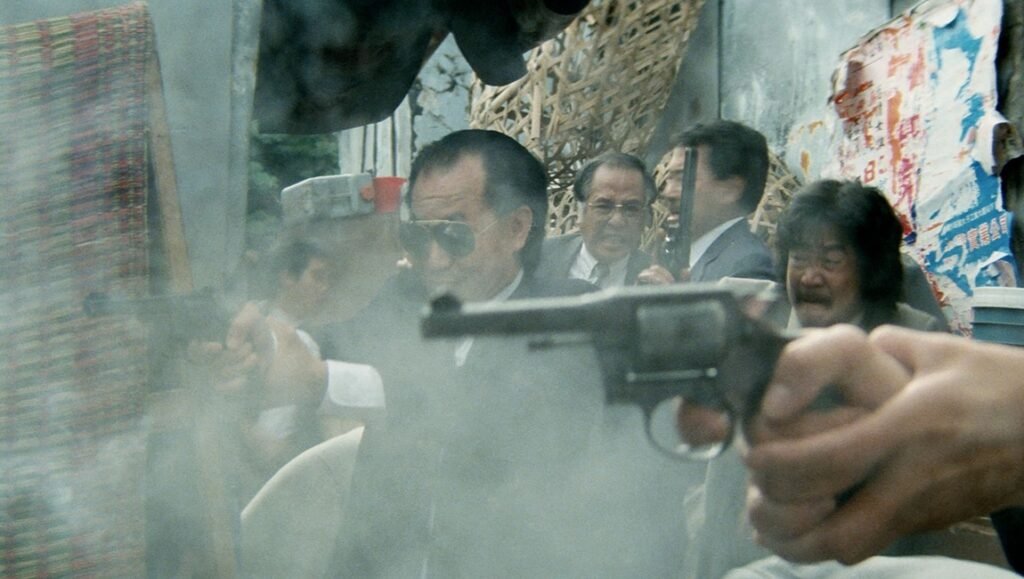

In the film, Chan plays an obstreperous though honorable city cop named Chan Ka-Kui in the local version and Kevin Chan in international ones. The aftermath of the spectacular shantytown opening — different parts of which are duplicated verbatim in Bad Boys II and Tango & Cash — has Chan babysitting the unwilling witness Salina Fong (Brigitte Lin) as he gets caught up in a storm of crime lords (made possible through the context of Hong Kong capitalism) and corrupt cops (in a system set up by the British and with white men at the tippy top) that’s all worsened by a broken legal system (where the judges and lawyers still don the silly sartorial British white wigs).

The revered Maggie Cheung plays Ka-Kui’s girlfriend, May, who has more to do here than she often gets credit for. Her introduction comes with an understandable flustering at seeing Salina in lingerie and Ka-Kui’s jacket when he comes home late, forgetting his own birthday. The intense theatrical pout she puts on here never really fades from her face as she is always upset with Ka-Kui and his apparent toying with the lines of relational fidelity. Her scenes, though marred by the film’s typically 1980s misogyny, also show her exercising agency and repeatedly deciding to leave Ka-Kui for his misunderstood indiscretions. She doesn’t run back to him in tears: it is he who runs back to her, desperately explaining one thing or another that reflected poorly. The theatricality of both her facial expressions and physicality reflexively draws attention to the camp-like absurdity of the relationship: men are stupid, her performance murmurs with nuance.

Chan is rightly best known as an actor. At his prime, he was much more though, and his stardom often came at the expense of his underrated directorial chops. Police Story was his fifth time helming a project, and it’s clear from the opening action set piece at the shantytown that he is no novice in the chair. Like a good meal, Police Story is more than just the sweets (action). Many of the most memorable scenes are, in fact, straight comedy sequences: the shower conversation, the court mishap, and the incredible phone line shenanigans to name a few. All three of these scenes are also humiliating to varying degrees, a word entirely foreign to the language of modern action stars. The action in execution is often equally humiliating, with Chan being on the receiving end of big blows just as frequently as he delivers them.

Anamorphic lenses were standard in Hong Kong cinema at the time, especially in action films, because of both their accessibility and their wider canvas for recording action — they made it easier to make sure the fisticuffs were within the frame. Chan and cinematographer Cheung Yiu Cho also use them expertly for dramatic effect. Narrow interiors are widened through the typically anamorphic distortion, which makes it easier to exaggerate character blocking in innovative ways. The lie-abundant and yarn-filled conversation between Ka-Kui and Salina, including a snooping May, visualizes the various loyalties and tensions in the conversation through both the composition and staging of the three characters. At other times, the lenses help illustrate the ideological opposition of two superiors in the police force by placing them on the far ends of the frame (and thus pulling them even farther from each other than normal wide screen would). The photography — and Chan’s directorial handle of it — are integral to the film’s canonical status.

But Ka-Kui wouldn’t be Ka-Kui without the instantly recognizable musical cue that accompanies him. (In the Hong Kong version, that is. There are two other versions of the film with comically lesser scores.) In the original score, composer Michael Lai (also known as Siu-Tin Lai) builds, mixes, reimagines, and repeats a central and very-’80s synth theme. The ominous, repeating electric guitar keeps danger within kissing distance. They repeat a lot, too, sonically sandwiching the corruption and violence in a cyclical structure of riffs. The mix of pop and suspenseful classical instrumentation occasionally recalls the sounds of the James Bond world, a fitting influence for a Jackie Chan flick given his shared global appeal with 007. Chan also sings the outro-take and lyrical version of the main theme, where the lyrics greet us like an old friend with an upgraded lover. The accenting horns cast our hero as even more triumphant, and the more jubilant rendition plays over the credits and B-roll of his famous bloopers. It’s impossible to turn Police Story off early.

The climactic action scene where Ka-Kui recovers the suitcase that unravels his framing from the bad guys in the shopping mall, the monument of capitalism if there ever was one, is one of the all-time great action scenes. Said action takes a mildly darker turn that anticipates some of Chan’s more mature works later (New Police Story, Shinjuku Incident, The Foreigner), only on a slight scale. He means to inflict real pain instead of evading it. He wants to deliver justice rather than shielding the public from its miscarriages. The whole showdown between crime lord Chu Tao (Chor Yuen) and Ka-Kui takes place in a building that all but symbolizes capitalism, and the former’s crimes, it should be noted, are capitalism gone bad: drug dealing, bribery, and illegal business activities, etc. The incriminating object Chan seeks in the chase is even a briefcase! Taking him down in a mall is like arresting a priest at a church.

Our lead cop is ensnared by false accusations, slander, and false charges both on the job and at home. His relationship with May is one misunderstanding after another, some more understanding than others. This trend continues through the next two films in the franchise, too. The most egregious example of this duplicitous framing comes when the tape conversion between Ka-Kui and Salina, played aloud and without visuals, sounds more like hanky-panky than incriminating evidence. Things take an even more disparaging direction at work when he is wrongfully accused of murdering another cop. In both his domestic and professional life, Chan’s cop fights to prove his blamelessness. Sometimes, he uses less than noble means to do so since, for him, the end justifies the means.

For all that, Police Story doesn’t hide that it is, well, a police story. While nowhere near as bad as his later Rush Hour movies, the copaganda is inescapable. Police brutality is just part of delivering justice in these movies. It’s also the sad butt of the film’s final joke, as Ka-Kui beats up a defense attorney for threatening to report their penchant for brutality and violence. Some cops are bad, but they are kept to the periphery of the story and the policing industry easily survives their corruption. A few eggs may be bad, but the system is okay. The subalternity of the Chinese cops to their Western superiors in the British colonial system complicates things slightly, though they are mentioned mostly as a local contextualization and place setting more than serving any more subversive political purpose. Their absence could also speak volumes: it’s the Hong Kong police officers saving the day and not the foreign outsiders. It cannot be fully overlooked that Hong Kong was still technically a British territory in 1985, and nationalistic sentiments (like cop propaganda) from the perspective of the colonized inherently mean something different than when coming from the colonizer. These politics were an unavoidable part of the local context with the Sino-British Joint Declaration being ratified just a few months before the film’s release. Ka-Kui’s personal name can likewise mean “home’s promising youth” in Cantonese, and as such points with optimism to the future — a future of national self-determination, perhaps, with the date of the British handover of Hong Kong to China creeping closer.

Comments are closed.