One of the most impressive first features to debut in 2025 was My Father’s Shadow. Screened for the first time at the Cannes Film Festival, Akinola Davies Jr.’s debut is an extremely personal work. Set over the course of a single day in early-1990s Lagos, the film follows two young brothers as they spend time with their estranged father, against the backdrop of a country on the brink of political upheaval, during the hours leading up to the annulled 1993 Nigerian presidential election.

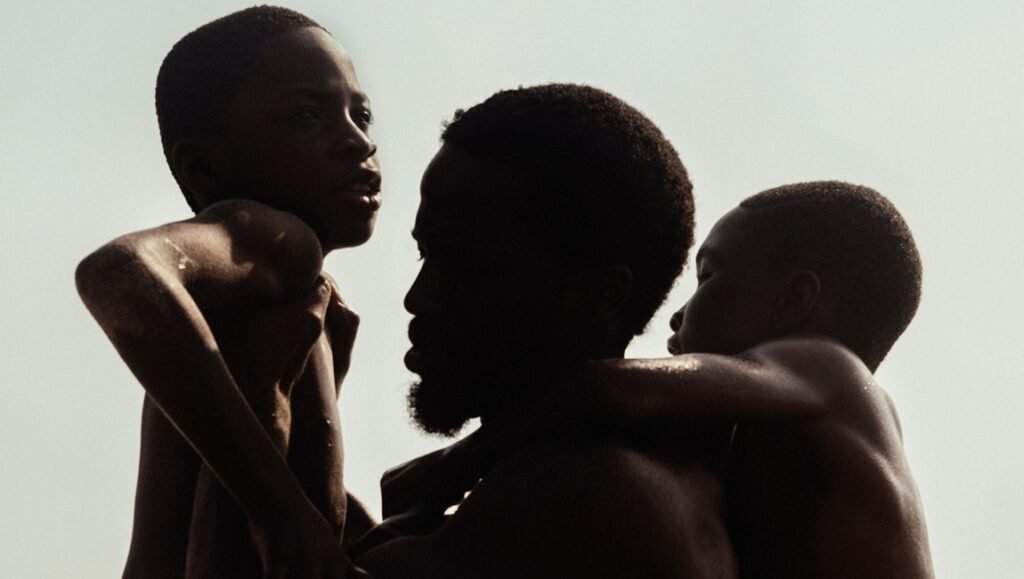

Moving between the intimacy of childhood memory and the wider turbulence of national history, My Father’s Shadow is less concerned with reconstructing facts than with capturing how memories are formed, distorted, and preserved. Davies Jr. chooses to portray the father figure almost entirely through the children’s point of view, turning him into a fragmented, elusive presence, at once imposing and tender, loving and unknowable; it is within this ambiguity that the film finds its emotional core. Shot on 16mm, the film embraces texture and imperfection as expressive tools, reinforcing the fleeting quality of remembrance. Anchoring the film is a remarkable performance by Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù, who embodies a masculinity that is both physical and deeply vulnerable, allowing the character’s contradictions to coexist without resolution.

Since its premiere, My Father’s Shadow has received significant recognition on the international festival circuit, earning awards and strong critical acclaim, and confirming Davies Jr. as one of the most compelling new voices in contemporary cinema. I sat down with Akinola Davies Jr to talk about My Father’s Shadow, discussing memory and generational trauma, fatherhood, childhood perspective, political history, and the challenges of transforming deeply personal material into a universal cinematic experience.

Omar Franini: What impressed me about My Father’s Shadow is the way you created and portrayed a story that is both a coming-of-age tale, something very personal for you, and also a compelling political portrait of Nigeria. What was the starting point of this project?

Akinola Davies Jr.: I made a short film in 2020, after having worked for a while assisting on short films and music videos. The short was called Lizard, and it was about memory, about an experience that happened to us when we were younger. I think memory is difficult to contextualize because everyone remembers things from a different point of view. Making that film with my brother was important for us. It was during COVID, so we didn’t get to travel to many festivals, but when we started writing My Father’s Shadow, my brother had already written a short film about spending a day with our father, whom we lost when we were very young. We both approached that idea from different perspectives: my brother really idolized our father, while I was more angry with him. So we tried to imagine how we would make the most of a day with him, if we could. We worked a lot with stories we’d heard about him from different people, using those as a foundation to create the character. For the two boys, we were both present, so we could draw directly from our own lives. More broadly, though, we wanted to give context to fatherhood, to absence in fatherhood, to grief from a child’s perspective, and to memory itself: how you can trust it, how you can’t, how malleable it is, how intangible it can sometimes feel. We also wanted the location to function as a character. The details you remember as a child — playing with friends or family, being surrounded by nature, that sense of curiosity about a place — all of that was really important to us. We were definitely trying to bring all of those elements into the film.

OF: The way you portrayed these memories is striking, and thinking about the opening — the sounds, the use of a handheld camera. Can you talk more about the idea of how to present these memories?

ADJ: I’ve been very lucky to have worked freelance in almost every department. I didn’t go to film school. I did a small film course, but I quickly realized that the beauty of cinema is how much you can embellish every element, whether it’s sound, costume, cinematography, or the story itself. You can really geek out in all of those areas. For us, sound was especially important. We wanted something that felt nostalgic, but also slightly supernatural, something that could transport you somewhere while still playing with nostalgia. Shooting on 16mm was part of that too, because it immediately creates that sense of memory. We used a lot of analog techniques, like film roll-outs or scratches on the film. With the sound design, we wanted it to feel very visceral, as if it was coming from different places. All of these things can trigger memory or provoke a physical response in the viewer. I love cinema, I know people talk about it struggling, but it’s still my favorite place to watch a film. You have the best sound, the big screen, the darkness, that sense of focus. So we tried to maximize every element for the cinema experience. It’s my first feature, so maybe not that many people will see it in a theater, but we really wanted to give the audience the most powerful, almost bombastic experience possible, through every texture of the film. And to go back to your question, I think that’s really it: texture is what allows people to feel memory, or a sense of resonance, when they watch a film.

OF: Remaining on the subject of memories, I’d like to talk about the father figure. As you said, both of his children have different reactions toward him, and I rather liked that you don’t focus much on this figure, but portray him through the children’s POV. This character is almost an enigma, a mystery to them, as much as he is for the audience.

ADJ: That’s such a beautiful way of contextualizing it. I think when you don’t know someone, you can either create this idea of them being a perfect person, which maybe some people would choose to do. But for us, to be a man, to be a human, is to be imperfect. And I think that’s what’s great about characters on screen or in real life. We really wanted to create a character that is not perfect. He has bad things. He’s full of holes. His life is not perfect. But we also wanted somebody who can be quite big and physical in this sort of masculine way, and at the same time very soft. And then the fantasy, the fiction in the film, is how we can fictionalize this day. What do we want to get out of it? How do you confront your father in a way that maybe you’ve never been able to as a child? That’s something we really tried to lean into. Even then, with memory, we have archive footage in there. We have aspects of newspapers, radio, all those things from the politics of the time, which is real. It really happened. We lived through it. But the children are our perspective. The camera is on their level. We see the world through them. We learn as much as they learn. That’s why we don’t focus so heavily on the father. Really, it’s an ensemble piece. Obviously, you need a lead and supporting characters, but I think all those things come together.

OF: This journey of discovery for the two main characters is not only about their father, but also about the political context. I rather loved the scene in the bar when they say that the election won’t take place. The people getting angry, especially the father, and I felt the anger. I felt transported. I know the political context of this period, but through your movie, I was there with the characters.

ADJ: I think it was really important, especially for a European, American, or global audience, to be interested in what’s happening. But not as in “I’m telling you off” — more like, come and feel it. Feel the disappointment. Feel the journey we’re going on. Because if we’re just giving you information about an election, you’re not coming along for the ride. It’s too much information. But if you know what the boys know and you feel the disappointment in that visceral way, then it works. There are only two times when the camera changes. One is in the bar, when the announcement is made. At the beginning we also have some handheld moments, but it’s about being patient enough to give you the opportunity so that when you get there, things feel unsettled. The film is also completely an invitation for the audience to learn more about Nigeria, to learn more about the politics, to learn more about what happened to a lot of us growing up in the ’90s. It’s not that long ago actually, maybe 20 or 30 years. I love that you see that, because cinema can be an opportunity to bring people into your culture and explain what’s happening.

OF: Speaking of the excellent actor you chose to portray the father, Ṣọpẹ́ Dìrísù, how did this collaboration start? Did you already have him in mind, and what kind of direction did you give on set to portray such an important figure for you?

ADJ: I’ll start with the second question. I didn’t really give him too much direction. When somebody comes into a space where two brothers have written a film about their dad, it can be quite intense. But we didn’t want him to be our father. We wanted him to be the character on the page, and his version of that character. When he came in, he asked, “Do you want me to be your father, or do you want me to be this character?” And we said, “We want you to be the character.” Because if you’re trying to be our father, you can’t reach this place. But you can reach this place, and we can meet in the middle there. For us, it was very important to allow him that generosity of spirit, to bring what he wanted to bring, and for us to welcome that in. We made a long list of people who could play the father, some American, some more Nigerian. Ṣọpẹ́ became the person because I’d seen him in two projects: a film and a TV show. There’s a film called His House (2020), [where] he looks very different in it, and then there’s Gangs of London. In His House, he plays a very sensitive, almost broken character, and in Gangs of London he’s very masculine. Seeing the diversity of his performances, I thought, okay, he can do it. We needed someone who fits this masculine persona, but who can also be really soft. Ṣọpẹ́ is incredible. He trained at a major drama school and learned his craft on stage before coming to the screen. He has such a generosity of spirit with the other actors. He grew up in the UK but has Nigerian roots, and the longest time he’s ever spent in Nigeria was on our film. So he came with insecurities and anxieties about how to perform this very Nigerian character. But he really leaned into everything that was going on, and into the fact that what he was feeling could be put into the character. He was the best choice. I love him so much.

OF: What can you tell me about the two young actors?

ADJ: They’re real brothers. It’s the first film they’ve ever been in, and they’re really, really wonderful. Marvellous, the older brother, is a very focused actor and very understanding of the themes we’re trying to execute. The younger brother, Godwin, is a bit of a rascal, but he’s very charismatic and very funny. A lot of the comedy in the film comes from his lines and moments like that. I think they bFfalance each other very well. I don’t know your family situation, but I’m the youngest brother and I have two older brothers. Watching them made me think about how much responsibility your older sibling has for you, something that, as a younger brother, you maybe don’t fully realize. This idea of protection, of taking care of you, this responsibility that the older sibling feels more than the younger one. I saw that in both of them. They worked really well together and encouraged each other. Even before we cast them, we did a workshop, and they were very good at working with the other kids, encouraging them, showing them what to do. Working with a 12- and an 8-year-old is very tough. But we had a very good team around them, and we encouraged them to play, be themselves, and bring themselves into the characters.

OF: So you gave them a lot of freedom on set?

ADJ: Yeah, a lot of freedom. The first week, less freedom, and I saw how difficult that was. Children want to be children. If you try to force them to do something, they don’t enjoy it, and it shows in their performance. After the first week, once we got to know each other a bit more, we allowed them to be themselves. I think it really shows in their performances. They felt very free and were able to enjoy what they were doing.

OF: You can really feel their chemistry. And as a wrestling fan, I loved the sequence where they talk about wrestling, because it helps situate the story in a specific time period, here, the early ’90s. I wanted to ask you more about that context.

ADJ: We used to get TV from maybe three or four o’clock until midnight. The first few hours were kids’ TV, and on the weekends there was loads of wrestling. We used to watch wrestling, Hulk Hogan, Andre the Giant… My brother loved getting the wrestler toys, and when we couldn’t get them, we would make them out of paper. There were a lot of popular culture references in Nigeria that people around the world were also sharing at the same time. We thought it was really important to encourage the things we were genuinely interested in as kids. Because it was very specific to us, we realized it was also very specific to you and to people elsewhere in the world. So many people comment on the wrestling scene. I think it’s about embracing those things that, as a child, you’re really into, but maybe don’t follow as much when you grow up. The mundane things were what we wanted to focus on, because we realized that kids all around the world were into those same things.

OF: What were the other main challenges of making this movie, maybe from a production point of view?

ADJ.: That’s a great question. As a director, I’m very protected, but now, having made the film, I realize how many challenges there were. We had a lot of locations, and we were shooting in a big metropolis that isn’t very used to arthouse films. They mainly shoot commercial films. We were shooting on film, 16mm, in Nigeria. My gaffer thinks it might be the first film shot on 16mm there, or at least in the last 30 or 40 years. I like shooting on film because of the pace. It allows everyone to be more present with each other. But with 30-degree heat, multiple locations, and children as your leads, it was really challenging. Everything was challenging. There wasn’t a single day that wasn’t challenging. But that’s also the beauty of filmmaking. With a good team, you go through the challenges together. You write a film, then you make it, and it becomes something different. Then you make it again in the edit, and it becomes something else entirely. Some of the crew came from Europe, and working in a Nigerian environment was quite tough for them, especially in the first few weeks. It’s an ambitious film, as you can imagine. But we really bonded, and I think that’s the beauty of the whole experience.

OF: How was the reception of the movie in Nigeria? Probably most people don’t know about the rich film industry there, so I was wondering how My Father’s Shadow resonates there.

ADJ.: Yes, it’s a huge one, a really huge industry. I think there were a few different impressions of the film. Initially, there was some skepticism. People were like, “Oh, this film did what it could. We’re not sure it’s a real Nigerian story.” But when people actually saw the film, they were very overwhelmed. The film opened up a generational conversation. For the younger generation, because we were under military dictatorship for a long time and history wasn’t taught in schools, this was their first introduction to what happened during the election in 1993. For the older generation, it was seeing their lived history on screen. So there was this duality, with generations coming together to understand their history and what had really happened in Nigeria. It was very overwhelming, in a good way. Younger people were speaking to their parents and fathers, and there were lots of conversations on social media. The film received a lot of support and a lot of love. The reaction has been beautiful. I think we need to try and do another release in Nigeria, because with the awards and the festivals we’ve been part of, more people are hearing about the film. It’s a big country, so not everyone hears about everything at the same time. But Nigeria has been really supportive, and I also have to say that all of Africa has been very supportive. Europe and England have been very supportive as well. It’s fantastic meeting people like yourself, from Italy or Germany, who have such an emotional response to the film. I think cinema is universal. It’s for everybody, for sure.

OF: I don’t really like to mention other movies during these conversations, but the way you spoke about generational memory made me think of O Agente Secreto by Kleber Mendonça Filho, because there’s a parallel with what happened in Brazil in the ’70s and in Nigeria in the ’90s.

ADJ: Yes, absolutely. The film did really well at the São Paulo Film Festival. Through films like O Agente Secreto, I learn about Brazil as well. I think this generational aspect, especially for people from the Global South, is about being able to revisit our history for ourselves, and also inviting people from the rest of the world to learn about that history. This year in particular, I’ve noticed a lot of films dealing with fatherhood and generational themes, like Sound of Falling, Sentimental Value, and O Agente Secreto. Many of us are grappling with similar ideas. But you can see, across all these films, how culturally and texturally different they are, even when they share similar themes. And I think that’s a really beautiful thing, and also a very powerful one.

Comments are closed.