Luis Buñuel didn’t think much of the Joseph Kessel novel that was the source material for his 1967 adaptation of Belle de Jour and mostly took on the project because he wanted to make it into something he liked. He didn’t have a good time making the film under the occasionally interfering hands of the Hakim brothers, and found star Catherine Deneuve to be a prude who didn’t want to fully take her clothes off and a performer who’d been hoisted upon him against his will. He still wound up with a Golden Lion-winning arthouse hit, and perhaps the most enduring film he ever made. Sex sells, especially when it’s high quality, and Belle de Jour’s blend of the everyday with the fantastic is perhaps the most perfect expression of surrealism’s erotic qualities since Buñuel’s own 1929 classic Un Chien Andalou. A film about the repressive sex lives of bourgeoisie dullards found its way to precisely the people it was intended for: the ones on the screen.

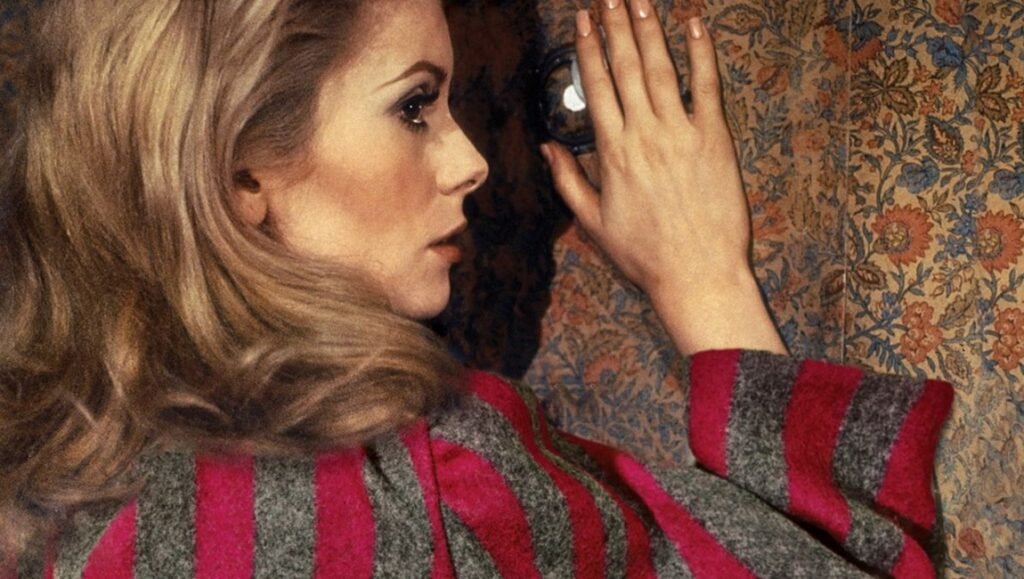

Deneuve’s Séverine is the ideal of a housewife on paper: blonde, beautiful, insipid, and stuck minding her home for her equally beautiful and boring doctor husband Pierre (Jean Sorel, a rare case of a successful actor’s most famous role making him look like a non-actor). They don’t have sex even though they’re close to perfect for each other in their pretty flawlessness. She’s physically healthy, but the mind doesn’t play by logical rules when you’ve got nothing else to preoccupy yourself with, and her fantasies and darker memories of a childhood touching incident bleed into her life right from the start of the film, as indistinguishable from reality as any of our own reveries of memory. Only those occasional flashes of her internal life, where she gets tied up and has mud chucked at her face, are what’s keeping her from having the inevitable standardized missionary sex with Pierre on a regular schedule, with occasional procreation of genetically perfect children as part of the bargain. Séverine, as it turns out, isn’t so much asexual as a submissive who’s gradually realizing what she likes, and a bit of prodding from her reluctant social acquaintance Henri (one of Michel Piccoli’s seedy pervert characters) leads her to a high-class brothel where she works part-time in the afternoons while her husband is at his job, none the wiser.

The world of the brothel inevitably is a more interesting place than Séverine’s perfect household, and it’s where the delineation of reality and internal lives really starts to go out the window (perhaps the one featured in the film’s final shot). There’s a deadpan, watchful Madame called Anaïs with lesbian dom tendencies and a knack for nicknames, coming up with “Belle de Jour” as a tribute to her daytime schedule. (She unfortunately has no knack for understanding this woman of a different class, who might as well be from a different species — the final scene between the two is an exercise in resigned frustration and suppressed feelings.) There’s a client with a fetishistic little box containing something that buzzes, which scares nearly everyone off from participating in whatever ritual he’s got in mind. (Its animal bent pairs interestingly with the recurring images and sounds of cats within Séverine’s own fantasies.) While the deliberate ambiguity of said client’s box inspired the greatest number of audience questions for an increasingly irked Buñuel (“it’s whatever you want it to be!”), the greatest impact within the film itself comes from one of the few Frenchmen who’d go on to rival Buñuel and his co-writer Jean-Claude Carrière as an auteur of perversities. Pierre Clémenti’s Marcel is a gangster who covers himself with leather on his skin and metal on his teeth, and carries that style into his trysts with Séverine, which finally allow her to open up with Pierre.

Belle de Jour contains no music (although the bells at the start and finish could be argued as such), and other forms of entertainment such as television or movies don’t come up at all. One gradually realizes that all the focus on sex, or lack thereof, is a testament to how few other things there are to do when you’re comfortable and unthinking. It has old-fashioned horse-drawn carriages in its surreal bookends, and various styles of the past frequently elbow their way in via dreams and reveries, but the brothel is a classy enough apartment in contemporary Paris, and Marcel’s leatherhead outfits (reportedly picked out by Buñuel himself) were decidedly ahead of the curve in 1967. Deneuve’s own incredibly influential Yves Saint Laurent wardrobe, which shifts from prettily bourgeoisie tastefulness to the most cutting-edge pieces of a designer at the peak of his powers, sums up the entire gestalt. At once both aggressively modern and a classical throwback, the film is about, and features, two versions of high-class tastefulness unable to totally reconcile with one another even when they’ve potentially got the great uniter in front of them. The more jumpy styles of Jean-Luc Godard may define what we consider 1960s postmodernism on film, but perhaps it was Buñuel’s more unemphatic disjunctions in time that were the most forward-thinking in their deadpan glories. (They would also be featured more overtly in Simon of the Desert and The Milky Way.)

As for Séverine herself, she’s one of the small handful of bourgeoisie characters who Buñuel ever found some well of sympathy for. She found her own way to do something like making Un Chien Andalou, and she did it by simply letting men do whatever they wanted to her and getting something out of it. Sadly for her, prostitution may be an older profession than filmmaking but it’s never as respectable. Her idealized allure culminates in Marcel shooting Pierre out of jealousy before then being killed by the police, with the now-paralyzed and blinded Pierre being informed by Henri of his wife’s Belle de Jour identity that caused all this. Séverine, ever the submissive, lets him do what he wants and subsequently goes through one final torment in order to look for an unclear sign of what her husband thinks of this announcement. The film began with a carriage ride that led Séverine to a rough fantasy, and it ends with us watching that same carriage roll by with no participants in it. Is it really such a good thing that her daydreams now seem to have no real connection in them?

Comments are closed.