In those chilly days of the Romantic poet, Samuel Coleridge sought to distinguish two synonyms. What is imagination, and what is fancy? He had this to say: “Imagination I hold to be the living Power and prime Agent of all human Perception, and as a repetition in the finite mind of the eternal act of creation in the infinite I AM. Whereas, the Fancy is indeed no other than a mode of Memory emancipated from the order of time and space; while it is blended with and modified by that empirical phenomenon of the will, which we express by the word CHOICE.” In these winding definitions, we must understand the key discrepancy: by Imagination, Coleridge understands human insight into something actual, by which the mind can disambiguate the nature of reality. By Fancy, he means mere invention, the rearrangement of things seen and wondered at. In our present, mechanical world, these two modes are married together; there is no truth greater than the empirical, and anything dreamt up outside of weights and measures is all the world of Fancy. We have, perhaps in respect of this, grown to better esteem the province of Fancy: because if it does not contain a metaphysical truth, it nonetheless directs us to our own reality. It is the business of clever artists who can metaphorize the universe. But we do not suppose that the poet has a closer access to reality than the scientist, or the cynical critic; the poet is instead an artist outside of reality, lost in clouds.

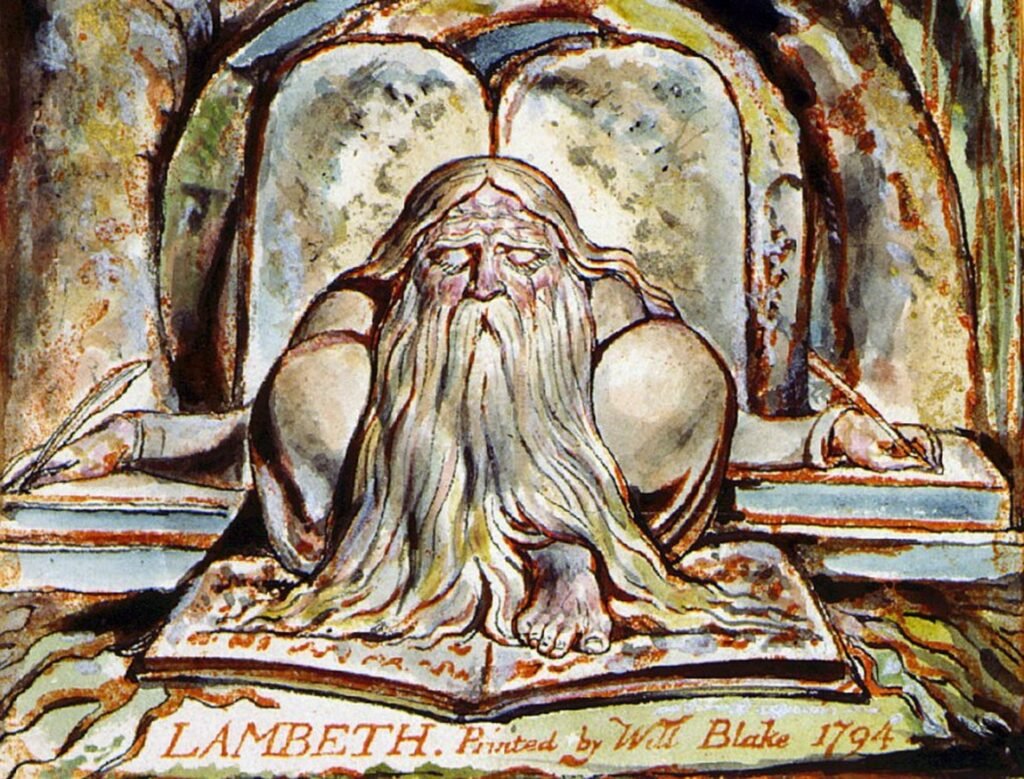

William Blake is the patron saint of the true imagination. In his vast cosmology, he imagines a fallen world saved and maintained by Los, the Eternal Prophet, who represents mankind’s imaginative capacity. To dream, and imagine, is not to escape the physical truth, but rather to access the full span of reality: “If the doors of perception were cleansed everything would appear to man as it is, infinite / For man has closed himself up, till he sees all things through narrow chinks of his cavern.” There is, in the mind of Coleridge, and in the mind of Blake, a much greater human existence than that which we encounter in the “vegetative” reality. We might say the same for David Lynch, whose films often tease at powers or principles outside of our grasp; in Twin Peaks we visit these unseen dimensions, peopled and governed by strange figures not dissimilar to the various “eternals” of Blake. Lynch’s unwillingness to openly explain his work is also, in its way, Blakean: he invites his audience into a forest of obscure, personal symbolism; part of the artwork is in encountering the artwork, through which an audience must engage their own creative devices. But the imaginative work is, on this principle, not wholly contrived by its maker — creativity is the harnessing of some outer substance, which travels through the artist. Blake is a master in the description of inspiration.

Los flamd in my path & the Sun was hot

With the bows of my Mind & the Arrows of Thought

My bowstring fierce with Ardour breathes

My arrows glow in their golden sheaves

My brother & father march before

The heavens drop with human goreNow I a fourfold vision see

And a fourfold vision is given to me

Tis fourfold in my supreme delight

And three fold in soft Beulahs night

And twofold Always. May God us keep

From Single vision & Newtons sleep

This Lifes dim Windows of the Soul

Distorts the Heavens from Pole to Pole

And leads you to Believe a Lie

When you see with not thro the Eye

That was born in a night to perish in a night

When the Soul slept in the beams of Light.

Compare this to Lynch’s own obituary-tag: Keep your eye on the donut, not on the hole. These sentiments are essentially the same. To see through and not with the eye; which is to say, to look through the window, not at the glass. To look at something directly and empirically is not necessarily to comprehend it: the direct center of the donut contains a specific absence of donut. Said absence is also constituent to the whole, so long as the whole is also perceived: both artists exhort their public into another kind of seeing.

Eraserhead is then a film about its obvious material concerns and a film that is about something else. The imagery leverages parenthood as much as it represents parenthood. In the first scene, we are in the cosmos: a sperm-like creature is produced by Spencer’s translucent self, which is then attracted to an egg-shaped planet, into which it must submerge. The bright line of invention results. This is the overwhelming theme: of conception — of somehow producing an entity that then exists beyond the self, which then collaborates with an external reality and metamorphoses into a new form. The anxiety is therefore in production of any kind — the development of any thought or idea, which originates in the self but must necessarily pass thereon, and develop independently. It is not always that one’s mind is a bow and his thoughts are arrows. Lynch inverts the optimism of Blake’s mental control to imply that certain productions of the mind are in some way unwelcome, or obscure. That one may be faced with the maintenance of a concept, which may grow with or without, that may come to dominate its apparent maker — such things are made without intention, much as a child is created without the active participation of the mother or father: a child is conceived, but after this moment its building is wholly automatic. One trusts in the reality of the universe to piece it together; one expects, or hopes, that the result will be in some way pleasing. If it isn’t — as in the narrative of the film — then appears a strange clash of obligation and revulsion.

This is not merely in relation to childbirth, but all kinds of birth: to contend with the output of the mind, in its being at once a part of and abstract to the self, existing at once as an extension and a contradiction of the self. Lynch poses women in a similar manner to Blake: they are the shadows of men; which is to say, they are the feminine aspect of a single being. Spencer has a twofold aspect at least: of his fusty wife and the seductive neighbor. Between whom there is both duty and desire, there is reproduction and there is jealousy, there is push and there is pull. This double-woman is mirrored by a cosmic double: there is the man in the planet, who seems to have a vaguely malevolent presence (in some way responsible for the physical, creative mechanism – the “egg”); and there is the woman in the radiator, who seems to have a vaguely benevolent presence (in some way responsible for the immaterial, transcendental possibility — the “light”). Between the cosmos and the actual is a semipermeable membrane, through which (in dreams, sex, imagination) Spencer is capable of travelling; here he is capable of seeing, within the context of the fiction, an objectivity beyond empirical sight.

The name of the film is worth considering in this context. Eraserhead: the device with which someone intends to delete. Spencer’s nightmare — in which he is supplanted by his own creation, and his brain is used to produce pencil-lead — seems to be a reasonably direct expression of the reverse thesis. That Spencer’s brain is capable of creation, and that the creative principle can be abstracted from Spencer himself. The pencil is capable of writing, much as Spencer’s child seems independently capable of existence; and moreover, the pencil cannot be produced without taking from Spencer’s self. The pencil itself cannot write without wearing itself away. The chain of invention is one of depletion and transformation: of objects and ideas moving between forms. There is an exchange in the creating of something: a gift of some portion of the self, the physical and the spiritual, which is then forever sundered. In Blake, union is holy and division is decay; in Lynch, we are in some ambiguous territory between. In Spencer’s dream, he both envisages himself as somehow combined with his progeny, while at once finding himself separable. Such angst is what leads Spencer to his strange infanticide, as teased by the woman in the radiator stamping on various sperm-like protrusions — though it appears less a murder than it does a final transfiguration: a necessary stage, by which the “child” morphs, the “planet” reveals its innards, and Spencer can at last enter the light.

And so, we return to William Blake, to Chapter VII of his The First Book of Urizen:

1. But Los saw the Female & pitied

He embrac’d her. She wept she refusd

In perverse and cruel delight

She fled from his arms, yet he followd2. Eternity shudder’d when they saw,

Man begetting his likeness,

On his own divided image.3. A time passed over, the Eternals

Began to erect the tent;

When Enitharmon, sick,

Felt a Worm within her womb.4. Yet helpless it lay like a Worm

In the trembling womb

To be moulded into existence5. All day the worm lay on her bosom

All night within her womb

The worm lay till it grew to a serpent

With dolorous hissings & Poisons

Round Enitharmons loins folding,6. Coild within Enitharmons womb

The serpent grew casting its scales

With sharp pangs the hissings began

To change to a grating cry,

Many sorrows and dismal throes

Many forms of fish, bird & beast

Brought forth an Infant form

Where was a worm before.7. The Eternals their tent finished

Alarm’d with these gloomy visions

When Enitharmon groaning

Produc’d a man Child to the light.8. A shriek ran thro’ Eternity:

And a paralytic stroke;

At the birth of the Human shadow9. Delving earth in his resistless way:

Howling, the child with fierce flames

Issu’d from Enitharmon.10. The Eternal, closed the tent

They beat down the stakes the cords

Strech’d for a work of eternity:

No more Los beheld Eternity.11. In his hands he siez’d the infant

He bathed him in springs of sorrow

He gave him to Enitharmon.

Comments are closed.