Our top 25 performances, before whittling it down to the 10 you’ll find below, featured votes for two actors from Manchester by the Sea, two from Toni Erdmann, four from Happy Hour, four from Certain Women, and a hefty five from Moonlight. A twist on a typical year’s voting trends which may find one or two double-dippings, it’s perhaps no coincidence that most of these films likewise ended up in our Top 10 films of the year. Solitary standout performances are something to take note of, but the sheer amount of powerful ensembles in 2016 is an all too rare cause for celebration. Luke Gorham

10. It’s disheartening to see how much Oscar talk that openly ignores his actual performance Casey Affleck has garnered this year. The discussion has tended toward whether Affleck is “deserving” of the award, according to an amalgam of arbitrary blogger-defined criteria to the role a sexual harassment case from a few years previous plays in his accolades (the seriousness of which should not remotely be diminished, though framing it within the context of movie awards season feels more than a bit disrespectful to the real-life parties involved). As for the performance, it goes beyond flashy descriptors; there’s no real-life subject to impersonate and no disability to exploit. In Manchester by the Sea, Affleck is given a far less noble task: to play a deeply unlikeable malcontent, one who seemingly goes through little to no change throughout the film. It’s through this grouchy character that Affleck’s able to mine a deeply humane portrait of grief, one that doesn’t simplify suffering into basic tics but fully envelopes a scale of heartbreak unimaginable to most. Even if you don’t like Lee by the end of Manchester, you understand him. Paul Attard

9. It’s perhaps unsurprising that a Maren Ade film exploring the sinews of the remaining relationship between a father and daughter would produce a pair of remarkable, measured performances, but it’s Peter Simonischek, as the prank-addicted, determinedly bizarre dad, who proves most affecting in Toni Erdmann. Still, nowhere is his brilliance more on display than in a late-film impromptu piano duet with his co-star, which takes place at a random Romanian Easter celebration that the two attend. The daughter at first mumbles and then transitions into an audition-worthy belting of Whitney Houston’s massive power-ballad, “The Greatest Love of All,” while Simonischek allows a lost lifetime of emotions to play across his face, from knowing glances, to paternal pride, and finally, deep concern. For nearly all of the film’s runtime, Simonischek is asked to vacillate between lame-dad absurdism and genuine poignancy, and it’s a moving balance that he fully masters. LG

8. The four leads of Ryusuke Hamaguchi’s intimate, exquisitely balanced ensemble drama Happy Hour shared the Best Actress prize at last year’s Locarno Film Festival. First-time film actors all, their performances are unaffected and natural, but delivered with a care and precision befitting their theatrical origins. (Hamaguchi developed the film through improvisational workshops in Kobe, Japan, where much of Happy Hour takes place.) In lieu of writing about all four of them here, let’s single out Sachie Tanaka, whose wonderful work as Akari, the rigorously honest and hardworking nurse, adds levity and wit to Hamaguchi’s portrait just as Akari’s no-bullshit attitude and tough love keep her friends and colleagues depending on her for support. Tanaka’s deliberate manner of speaking, casually cool physicality (even when hobbling on crutches in the film’s final stretch) and sharp gestures make Akari a compelling and utterly believable presence in Happy Hour. She’s a woman that many often encounter in life but all too rarely in films: smart, skilled, sardonic, devoted to but not defined by her job, intensely loyal to her friends and not ashamed to expect the same loyalty from them in return. It seems no coincidence that in English, her character’s name translates as “the light.” “Your name suits you,” Jun says during a moment of mutual connection on a weekend getaway. “You make us all bright.” Tanaka’s incandescent performance does much the same for Happy Hour. Alex Engquist

7. Adam Driver’s reading of his character’s poems in Paterson represents a rare synergy of form, content and performance. His voice matches the material, which is mundane and unadorned, erupting into trembling beauty when least expected. It’s no wonder this is the conceit with which Jarmusch chooses to open his film, and which he returns to throughout. Driver’s performance possesses a quietude that can just as easily capture both sublime awe and the bored patience with which one listens to a coworker’s woes. As a film about working class people who express grander aspirations, its lead spends much of his time simply listening. At times it’s deliberate, as when he’s with his artist girlfriend, Laura (Goldshifteh Farahani); at others, he simply listens to the conversations of passengers on his bus. And even when the dreams are big or the conversations ridiculously precious, like the kids from Moonrise Kingdom discussing whether they’re the only anarchists in town, the amusement on Driver’s face never veers towards condescension, instead conveying a patient joy that exudes the same supportive attitude as Jarmusch’s camera. Chris Mello

6. Zhao Tao is the sad, resolute heart of Jia Zhangke’s surreal melodrama, Mountains May Depart. She opens the film leading a community in dance to the Pet Shop Boys’ “Go West” in an exuberant vision of the promise of a newer, freer China. Long the wandering observer in Jia’s explorations of his modernizing homeland, Zhao has never had a chance to do be so expressive. And Jia, abandoning the minimalist style with which he made his name, for the first time foregrounds her performance, allowing it to dominate his film—from her character’s wrenchingly physical display of grief at her father’s funeral, to the internalized heartbreak of failures to connect with an estranged son, to the quiet joy of a moment when she shares with her boy the music of Sally Yeh. In the end, Zhao dances to “Go West” again, alone this time, an old woman in the cold dawn of a forgotten city, dancing a lifetime of regret and hope. Sean Gilman

5. All of the women in Kelly Reichardt’s Montana-set drama, Certain Women, create indelible portraits of loneliness and quiet fortitude, but none quite embody those qualities as well as newcomer Lily Gladstone. Playing Jamie, a ranch hand who slowly becomes enamored with a young lawyer (Kristen Stewart) who’s teaching night classes in her town, she manages the tricky feat of underplaying without once coming across as opaque. (And opposite Stewart, no less.) Hers is a performance of grace notes and small gestures, gentle and expansive, able to convey gulfs of longing within a single glance. (A nighttime horse ride and a truncated roadside goodbye are stunners.) At the end of the film, as the circadian rhythms of Jamie’s routine start anew, there’s only Gladstone’s expression and the static crackle of a radio—no more is needed. Lawrence Garcia

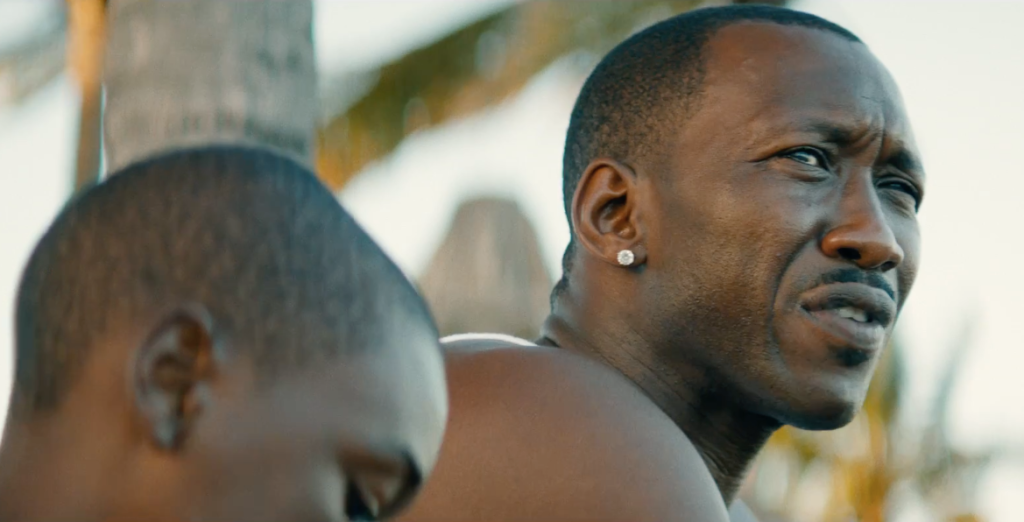

4. In a year that underscored divisiveness, director Barry Jenkins gave us a much-needed dose of compassion with Moonlight. Brimming with humanity, Jenkins’s careful work and Tarell Alvin McCraney’s affecting story would be lost without the wealth of talent poured into the characters—Alex Hibbert, Ashton Sanders, and Trevante Rhodes build a persona with tacit force at pivotal points in Chiron’s young, teenage and adult life, respectively; and Naomi Harris effortlessly fuses fierceness and fragility in her drug addicted mother role. However, it is Mahershala Ali—as Juan, a complex, yet not conflicted, drug dealer—who anchors Moonlight with empathetic weight. Juan takes a rudderless Chiron (or “Little,” as the character is referred to when he’s a kid) under his wing in a gesture of understanding rather than sympathetic charity, richly drawn by Ali’s spoken and unspoken acts of generosity. Chief among them, an impromptu swimming lesson where Juan takes Little into the ocean and teaches him the beauty of trust and the power of confidence. But nothing compares to the emotional earthquake set off by Little asking, “What’s a faggot,” and Juan’s response, performed with such surprising and thoughtful poise it nearly knocks you out of your theater seat. Kathie Smith

3. More than a mere adaptation of an often forgotten Jane Austen novel, Love and Friendship finds director Whit Stillman engaging in open dialogue with one of his most crucial stylistic influences. In protagonist Lady Vernon, star Kate Beckinsale is the embodiment of Austen’s classicism and Stillman’s contemporary touch, the walking representation of one artist channeling another and conversing across time and space. Beckinsale tackles Austen’s dialogue while following Stillman’s knowing direction, and creates an utterly unique film character that seems as inseparable and organic to the Victorian setting as much as she is foreign and incongruous to it. Beckinsale handles this tricky dual approach with singular wit and intellect. Her tongue is sharp as a dagger, yet her features are soft, and Stillman baths her in soft light and sets her against opulent scenery. She gives a formidable performance that’s somehow even larger than the bombastic roles she’s taken in Hollywood actioners. Temporarily unburdened by CGI excess, she takes full command of the screen and reminds why she’s one of contemporary cinema’s most interesting and engaging performers. Drew Hunt

2. One scene in Kleber Mendoça Filho’s Aquarius finds its principle actress, Sonia Braga, absolutely firing on all cylinders of fury—her Clara attacks the racist, classist assumptions of a young “business graduate” who’s used every dirty trick he can to drive her out of her home. In other scenes, Braga’s Clara displays a natural tenderness; she’s a woman who finds great comfort and affection in the company of her extended family. The dichotomy is important because it’s keyed to that of the film itself, which prizes the shared experience of families, in their home, surrounded by that which they’ve accumulated, and likely intend to pass down: walls with stories, books, and most of all, records. Braga’s performance is great at least in part because it’s a conduit for the politically-charged thesis of Mendoça Filho’s film: a staunch defense of ownership rights—to objects and spaces—and a righteous rebuke of forces that plot against them. Sam C. Mac

1. With Elle, one of cinema’s greatest perverts has made his ultimate manifesto on guilt and shame and, especially, control. Without Isabelle Huppert, though, it’s very likely that Paul Verhoeven’s typically thorny point of view on sex and violence would not have cohered quite so powerfully. Huppert’s Michele simply refuses to play by anyone’s rules of either decorum, politesse, or victimhood, and the astonishment with which this is viewed by the film’s other characters is shared by the audience largely because of the actress’ complete embodiment of her character’s commitment, her delight in keeping everyone who might even minutely challenge her totally off-balance. It’s a performance of pure fucking steel. Matt Lynch

Comments are closed.