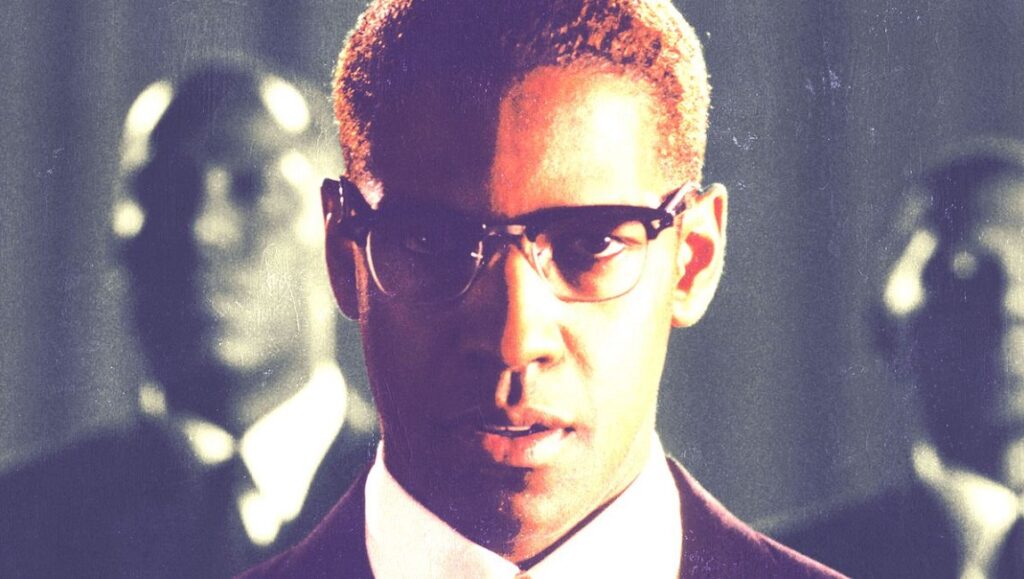

When Malcolm X, the epic biographical drama about the titular civil rights figure, hit theaters in November 1992, it came off the heels of a long and arduous process. Dramatizing the life and death of the polarizing Muslim minister had been a lifelong ambition for director Spike Lee, who had sought to bring Alex Haley’s 1965 book The Autobiography of Malcolm X to the screen for a long time. However, when the screenplay, co-written by James Baldwin and Arnold Perl in the late-’60s, was first given the go-ahead by Warner Bros. — the result of a 25-year-long effort by producer Marvin Worth — the studio wanted Canadian director Norman Jewison, whose bona fides included the seminal 1967 drama In the Heat of the Night, in the director’s chair. While Jewison was able to bring Denzel Washington onto the project for the lead role, there was public outcry over the fact that a white director was slated to helm the project. Lee became one of the leading voices of dissent, criticizing Warner Bros.’ decision, and making the incendiary claim that only a Black person could direct the film. After facing difficulties with the rewritten script, which had gone through numerous writers, including David Mamet and David Bradley, Jewison eventually bowed out and the studio let Lee take over.

Lee had previously cut his teeth with a stylish and vivacious 1986 debut, She’s Gotta Have It, a highly acclaimed, New York-set comedy-drama about a polyamorous woman and the three men she dates. Although he is often regarded as a primarily political filmmaker these days, it wasn’t until 1989’s Do the Right Thing that the politics, which had so far lingered in the background without spilling over into the text proper, would come to dominate one of his works. But even so, his filmography has since run the gamut from hot-button agitprop — perhaps best exemplified by the scorching, sledgehammer satire of 2000’s Bamboozled — to more intimate low-key dramas like 25th Hour, taking excursions into lengthy crime thrillers (Summer of Sam), polarizing — and underappreciated — low-budget work (Red Hook Summer), and remakes that were either somewhat interesting (Da Sweet Blood of Jesus) or utterly pointless (Oldboy). With the massive success of BlacKkKlansman in 2018, it’s easy to forget that Lee dwelt in directorial limbo for a decade and change, his post-Inside Man films hardly registering with the culture at large.

Things were very different in 1991, though, and as the young firebrand took over the production, many people had a lot to say about it. Chief among them was Black beatnik poet Amiri Baraka, who derided Lee’s film work, mockingly compared him to Eddie Murphy, and declared, “We will not let Malcolm X’s life be trashed to make middle-class Negroes sleep easier.” The two cantankerous artists exchanged barbs for a while, but the spat fizzled out unspectacularly. To understand the heated debate surrounding the film — which, notably, hadn’t even come out yet — it’s necessary to look at the state of Malcolm X’s legacy in the early-’90s. Even though the once-controversial Martin Luther King and his message had all but been assimilated by the political and cultural establishment at that point — a passionate fighter for social justice dulled into a figurehead for liberal platitudes about kindness and mutual respect, his pro-labor and anti-war stances completely sanded down — Malcolm X was still considered a dangerous, even hateful, radical by large swaths of the white population.

By contrast, his esteem in the Black community had risen steadily. The radicalism of the ’60s and early-’70s had given way to a reactionary backlash which culminated with the election of Ronald Reagan and reverberated well into the the presidency of George H. W. Bush, and later the Clinton administration. Sales of Malcolm X’s autobiography had increased 300% in the three years preceding the film’s release, the one-time Nation of Islam member having been given a second life by a new generation struggling for self-determination and dignity in an age of moral panics about “welfare queens” and tough-on-crime rhetoric that would see the rise of racially charged terminology like “super predators.” Numerous activists, academics, and rappers laid claim to Malcolm X, his ideas, and his image, while sometimes, ironically, sanding off many of his edges in the process as well. Lee, for his part, took on the gargantuan responsibility resting on his shoulders with characteristically offhanded bravado, saying, “I’m directing this movie and I rewrote the script, and I’m an artist and there’s just no two ways around it: this film about Malcolm X is going to be my vision of Malcolm X.”

As it turned out, Lee was right to be confident — Malcolm X captured the filmmaker operating at the height of his powers. The epic opens with a speech delivered by Malcolm X (Washington delivering in a career-best performance) over a shot of the American flag, a coy inversion of Patton‘s famous opening speech, which George C. Scott delivered in front of an enormous Star-Spangled Banner. Halfway through, the flag catches fire, its red, white, and blue fabric slowly burning away until only an “X” shape remains. On top of that, Lee’s keen understanding of history and documentarian sensibility both quickly come into play as well, as the fiery sermon is intercut with footage of Rodney King’s 1991 assault by LAPD officers — still one of the most notorious instances of police brutality in American history.

In Lee’s work, history regularly collides with the present in interesting, and often thorny, ways, and in Malcolm X that tension is particularly palpable. Taking the audience through various stages of the Black Muslim leader’s life — from his childhood and delinquent youth, to his emergence as a preeminent Black nationalist voice — the film interrogates how history affects both its main character, and the then-present of 1992. It makes repeated leaps through time, not only examining its subject’s life, but American history, Black American history specifically, while also recontextualizing the images and grammar of Hollywood cinema — the Patton-esque opening, the camera dashes that recall Martin Scorsese, the Nation of Islam meeting that’s staged like Charles Foster Kane’s campaign rally in Citizen Kane, and the final sequence of schoolchildren proudly proclaiming, “I’m Malcolm X,” an echo of the famous scene from Stanley Kubrick’s Spartacus.

The clash of drama and historicity reaches its zenith immediately after X is assassinated and his wife, Betty Shabazz (Angela Bassett), mourns over his lifeless body, tenderly holding his head in her arms. We hear her cries as the camera pans across the hall — marked by the chaos that ensued following the brutal shooting — and see her tear-streaked face, only for the film to smash cut to her husband being wheeled into the back of an ambulance, the shaky, black-and-white cinematography recalling newsreels of the era. Throughout Malcolm X‘s mammoth 201-minute runtime, the past continually invades the present — as the leader’s house comes under siege by members of the Nation of Islam, and he struggles to get his family out safely, memories of his childhood home being attacked by the Ku Klux Klan come rushing back — and Lee constantly reminds the audience that, amidst all the dramatization, these are actual events that took place, not only making regular use of grainy black-and-white, but also framing his actors in flickery ’60s TV sets and recreating recognizable photographs.

By the end, Washington’s Malcolm X appears to have an inkling of what will befall him. Sitting in his dressing room, ahead of what would be his final public appearance, he somberly reflects, “It’s a time for martyrs now,” seemingly aware that his troubles with the Nation of Islam will finally catch up with him. And later, as he is looking at the gunman who rushes his podium, a faint smile flashes across his face before the shotgun blast knocks him to the floor. But even with all the loss, pain, and suffering that X’s story ends on, the film’s final sequence moves beyond the tragedy, and turns toward the future, showing the civil rights leader’s words resonating long past his premature death, and inspiring a new generation of Black children all over the world. Future South African president, Nelson Mandela, who had just been released from prison the year before filming, ends the film by quoting what are perhaps Malcolm X’s most famous words: “We declare our right on this earth, to be a human being, to be respected as a human being, to be given the rights of a human being, in this society, on this earth, in this day, which we intend to bring into existence by any means necessary.” These final four words, delivered by X himself via archival footage, have lost none of their defiant power in the almost six decades since he first spoke them.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.