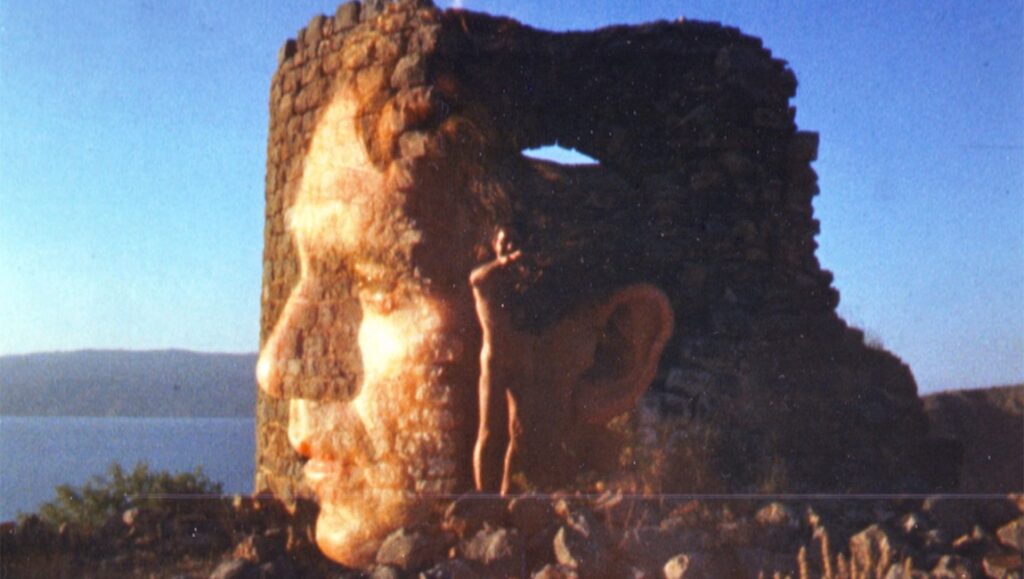

Robert Beavers’ 18-film cycle My Hand Outstretched to the Winged Distance and Sightless Measure, comprising the majority of both his filmography and a recent 25-film retrospective of his work at Anthology Film Archives, begins with just that. The film Early Monthly Segments opens with a bombast of images centered on outstretched hands in various forms (most strikingly involving a pair stuck out of a single small window at a cramped angle). They are interspersed with nude portraiture of Beavers and his long-time romantic partner in filmmaking and life, Gregory Markopoulos, on the wild beaches of a Greek isle. It continues as a sort of silent diary film encompassing the end of his adolescence and early adulthood, but it remained unprinted and thus unseen until circa 2003. Beavers would later add a soundtrack and use the opening three minutes of flesh in the primordial landscapes for the earliest completed film included in the retrospective, Winged Dialogue, but the remainder of Early Monthly Segments is the Big Bang of Beavers’ filmography. The Segments now serve as the opening to the cycle, and it is subsequently followed by the five films that utilize portions of its material to construct new works featuring soundtracks and additional footage: Winged Dialogue generally shares a reel with Plan of Brussels, followed by The Count of Days, Palinode, and finally Diminished Frame.

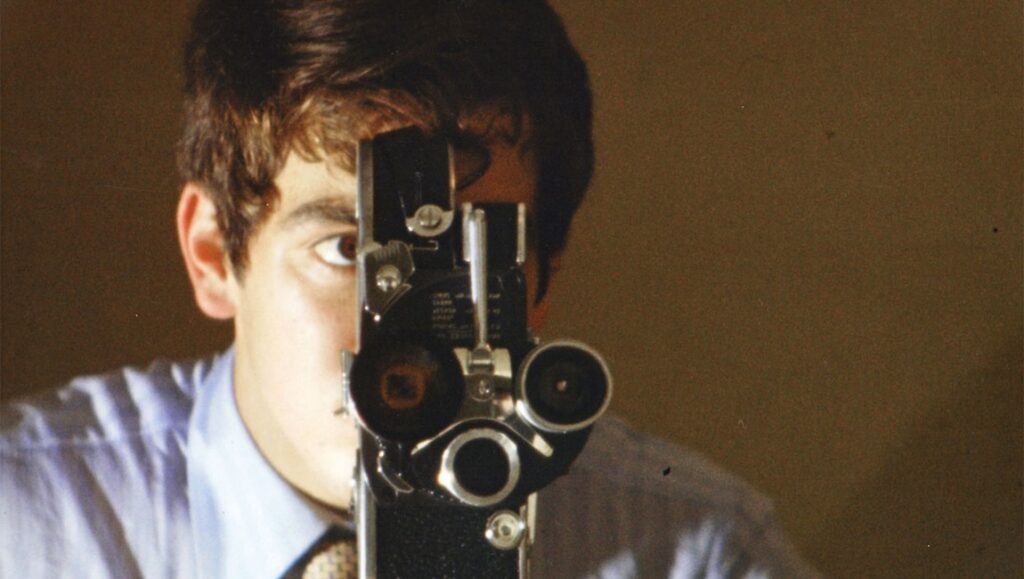

Beavers’ subsequent material for the Segments that he’d cannibalize would be heavily focused on different types of mattes and other forms of gamesmanship within his framings. Paper covers the camera in the footage that’d be primarily used for Plan of Brussels, square shapes that block out the center of the image dominate The Count of Days, disc mattes that turn frames into something shaped like CD covers are used for Palinode. Diminished Frame predominantly utilizes the diary material related to Beavers and Markopoulos’ life together, and Still Light (generally not included with the prior five) would use only two short scenes before Beavers finally transitioned away from the material entirely. The films are set apart from one another via soundtracks and new footage, even with Beavers’ fondness for the sound of birds taking flight tying them together. Also critical to the Segments is the recurring use of images centered on the process of him and Markopoulos making films, ranging from blatant focus adjustments and applications of filters to the lens, to a sequence of a splice being performed that would be reused alongside the outstretched hand in Still Light. Subsequent titles would continue the focus on craftsmanship in all its forms. It was not always documented on film, but Beavers would continue the process of making most of his movies for great stretches of time — the majority of the cycle would be cut down dramatically in re-edited running times decades later, such as Winged Dialogue going from around 16 minutes to just the opening three from Early Monthly Segments. Most would properly premiere significantly after their initial creation dates due to Beavers’ and Markopoulos’ extended withdrawal of their work from circulation, resulting in a chronology for the cycle based on the order they were started rather than finished.

Despite their similarities and points of comparison, mood and tone fluctuate dramatically throughout the first six films of the cycle. If Winged Dialogue is classically erotic, Plan of Brussels tackles cosmopolitan claustrophobia in how it transfigures Beavers lying in his room alone into a stuttering parade of shifted positions, featuring a recurring word on the soundtrack of excerpts from Belgian playwright Michel de Ghelderode that most Americans can recognize: “Lucifer!” The Count of Days’ use of a dissected mouse, with the dissection tools used to produce scratches on the film itself, is arguably even bleaker. The divided viewpoint is rendered even more uncanny by the square matte blocks obscuring the center of the frame, which is frequently divided up like a triptych. Even the scene from the Segments of Markopoulos holding a mirror over his heart that reflects light into the camera is more glaring than beaming in this context. Palinode hovers in the direction of being a narrative film about a male singer’s life in Zurich and his mysterious connection with a young girl that recalls the films of Joseph Cornell, but the approach is as fragmented as the opera excerpts that make up the soundtrack and as liquid as the iridescent colors that bleed into each other throughout. Diminished Frame’s jumps in time are called attention to by repeated sequences of Beavers applying color filters and mattes to a mix of black-and-white and color footage of West Berlin, with a soundtrack that literalizes the scars of World War II and fascism.

Still Light would find Beavers’ use of color filters that call attention to themselves rendered as even more of an organizing principle in structure. Colored light and square color plates play off each other and the face of a young man, before transitioning into a monologue about artistic creation from the older critic Nigel Gosling that is perhaps Beavers’ most explicit declaration of artistic principles in his filmography. The use of the monologue’s ideas about art-making feels like the launching point for the stratospheric highs of Beavers’ consensus favorite, From the Notebook of…, which utilizes Beavers’ own written notes on artistic creation to create a rapturous flurry of screen-dividing, page-turner edits that feel like they operate at the speed of a mind frantically scribbling their inspirations and flipping back through what they’ve set down on the page. In a film where everything Beavers sees is a potential source of creativity in form, it’s only fitting that From the Notebook of… is bookended by old favorites of Beavers iconography in new forms: the first time we explicitly see the birds that make his recurring sounds of wings in flight open the film, and one of his metafictional portraits of himself and Markopoulos closes it.

Work Done and Amor are further explorations on the creation process. Where Amor possesses a certain joie de vivre in its sequences focused on sewing a suit and rhythmic clapping to motivate the cuts to the film made by those same hands, Work Done is one of Beavers’ most excitingly shapeshifting in approach and tone, despite near-exclusively using square shapes in all their forms. The stitching of a book seems to imply the intensified beauty of the forests and rivers in the writing on the page, only for Beavers to show the forest being destroyed — the title of the film is both truth in advertising and the ultimate expression of Beavers’ interest in creation. Perfectly sculpted ice blocks open the film, and play off the stone rubble of a ruin that still retains traces of its prior architectural beauty. The film approaches a cheery sort of horror in its final sequences, with an uneasy tension produced via the beautifully intense red shade of a meal that happens to consist of cooked animal blood — one life force is drained to feed another.

One of only two Beavers films to go past the 40-minute mark that generally designates a feature film from a short film in its final cut, Ruskin is a visitation of sites across Europe associated with the art critic John Ruskin, with Beavers capturing the minutiae of the buildings he sees via careful framing of their forms in different lights and mattes, intercut with his trademark page-turner edits. It resembles both city symphony films and the work of Chantal Akerman, but the mysterious wipe-like edits against a black screen have never quite been duplicated before or since. A similar focus on artistic details is taken up by the unassumingly titled The Painting. The Painting uses The Martyrdom of St. Hippolytus, a painting featuring the titular saint torn apart by horses, as commentary on further internal divisions: a shattered window pane, dust particles drifting apart, traffic’s ebbs and flows, Markopoulos in shafts of light, and a neatly torn portrait of Beavers himself. Beavers and Markopoulos remained together and lived as nomadic European filmmakers centered around Greece from 1967 until Markopoulos’ death in 1992, but you could easily mistake The Painting for a film based on a lovers’ quarrel. Wingseed achieves a similar melancholy when it ventures into using shots of a naked man alone in a dark room, but those are dark interludes of isolation in a film that also manages to be as free-floating as the titular plant in its use of side-to-side camera movements: the soundtrack of goats’ bells and bleats transfigures the film into a piece about the solitude, both blissful and lonely, of shepherds. It’s one of the most Greco titles in the cycle, pipped out by Efpsychi’s recurring use of the Greek word “teleftea” (meaning something like “the last/the end”), and the letters of the Greek language resemble both storefronts and individual portions of the human face.

Sotiros, which is unique among Beavers’ re-edits for being a 45-minute trilogy of films that was then compressed into a single 25-minute film, finds Beavers using title cards for the first time, all saying either “He said,” or “he said.” It’s the closest thing to dialogue in a film that uses them as bookends for wordless sequences generally focused on the illuminations of the Sun as it shines down on Greece and an Austrian hotel room. Made after Beavers suffered a serious injury to his leg and eye in a bus accident, the title cards eventually fall away as his injuries take greater prominence: despite his wounds, the eye allows Beavers to heal, and the swiveling of a camera on a tripod provides the internal stability that his leg could not.

Beavers has called the completion of the final three films of the cycle “the fulfillment of this way of life” with Markopoulos, and his subsequent films would find him gradually settling into a more stable lifestyle centered on Switzerland and Germany. The exquisitely pristine The Hedge Theater takes the maxim “all the world’s a stage” and renders it transcendentalist: Baroque architecture’s grand marble columns are taken just as seriously as sources of beauty as a little theater made out of sticks in the woods. Sequences involving a buttonhole being sewn and Beavers returning to self-portraits of himself filming the movie deepen the allusions, and the final shift from snow to rain leaves one with a feeling of having witnessed a drama of the mind. The Stoas occasionally features shots of empty hands making a cupping gesture in a void-like space: the subsequent footage of the Greek wilderness at its most parodically lush and alive, right down to massive bushels of Dionysian purple grapes, achieves its beauty precisely by deliberately failing to capture the whole world in one’s hands. As the only film in the cycle to be started after Markopoulos passed away, The Ground is inevitably mournful: recurring sequences involve a man beating his chest, then holding out his hand as if to catch a falling tear from his offscreen face. They’re counterbalanced by the sights of one final work sequence: a man chiseling away at stone, implied to be making something immortal like the enduring ruins of Greek towers.

With Beavers now generally residing with the German filmmaker Ute Aurand in Berlin and returning to the United States more often in his filming, many of Beavers’ films since completing the cycle have skewed towards portrait-style works of shorter durations. The shadows have grown darker, and his whites are milkier. The three longer films since the completion of the cycle (Pitcher of Colored Light, Listening to the Space in My Room, and The Sparrow Dream) have found Beavers expanding his focus on the furnishings of the rooms one lives in, particularly that of his mother. Pitcher of Colored Light, the first film in his new cycle of sorts, is focused on Beavers’ mother, her house, and her garden. (She has a lamp shaped like a chicken that Beavers is particularly fond of including in the new films.) With his mother frequently the subject of loving close-ups (including a shot of her performing intensive-looking work in her garden) and allowed to give some of the first full sentences in a Beavers film since Still Light (she sings a song and then says it’ll be for her funeral), the seasons changing allows us to slowly soak up the unease one feels about loved ones aging.

In the other two longer films, Beavers’ own voice begins to finally appear on his own soundtracks, with his thoughts, memories, and dreams woven into a synesthesiac mesh. Listening to the Space in My Room emphasizes this permeability by seeming to float between different portions of the house Beavers lives in while capturing muffled portraits of the people he lives with, including an obscured Aurand. The key line is a recitation from a text about the intuitive nature of love and friendship: a model of how Beavers feels about the people he cares for the most and tries to capture in his work. Childhood picture books of Greek mythology and a return to locations he’d filmed half a lifetime ago are part of the journey undertaken in The Sparrow Dream, and it features a return to footage of his mother, now in a nursing home and no longer capable of being as active as she once was: no one can really go home again after a certain point.

Among the miniature homages, most have a similar quality of trying to capture something Beavers loves before it fades away, and they tend to be associated with friends who have passed on. The Suppliant focuses on a small Greek statue from a now-deceased friend’s residence, while the soundtrack of fast-paced pencil scrawling makes this feel like a slightly urgent sketch, lit in bronze and flexing its muscles. “Der Klang, die Welt…” is focused on Beavers’ landlady and her then-recently deceased husband’s love of music, capturing the two performing a Bohuslav Martinů arabesque in their studio via a series of miniature grace notes generally centered on their interactions with their furnishings. Among the Eucalyptuses uses fades and quick camera movements to capture a sense of the world fading, but it’s his newest film (and potential conclusion to this new cycle) Dedication: Bernice Hodges that ties up all 25 films shown in the retrospective into a loop. A tribute to a woman who Beavers first met at age seven who taught him how to carve wood, he first attempted to film her in 1966 but was disappointed with the results. After throwing away nearly everything except two short strips, he has belatedly constructed a delicate tribute based around rephotographing the strips on a Steenbeck and returning once again to images of an ashtray he carved and his own work on splicing together this film: the self-portraits of him at his work, inviting the audience to take a look at the process of his creations, retain the same spirit from his adolescence to the present.

Comments are closed.