Sci-fi books and movies have been enamored with the remarkable possibilities of, and dangerous risks inherent to, artificial intelligence for almost as long as the genre has been around. HAL needs no introduction, of course, nor does Skynet, and Donald Cammell’s underrated Demon Seed is almost 50 years old now. But Franklin Ritch’s The Artifice Girl is arriving right on the cusp of a new found fascination with the subject, as ChatGPT and AI art have taken the world by storm. Think pieces both for and against are strewn about all over social media, with tech companies touting endless applications that may or may not ever come to fruition. Could this ultimately all be to the betterment of the human race? Or is it just another venture capitalist-funded shell game? We don’t know yet, but The Artifice Girl suggests some new potentialities to fret over.

Ritch’s film approaches this complicated subject with a certain ambivalence, concocting a low-budget, extremely lo-fi chamber piece that centers around philosophical questions of ethics and morality, and whether or not these things apply to a fully artificial intelligence that just happens to look and sound like us. Divided into three discrete chapters, plus a brief prologue, each part of the film takes place in one location, with mostly the same cast, but spread out over the present, then the near future, and finally decades later. Chapter one introduces Gareth (played here and in chapter two by the director himself) as he interviews for what he thinks is a grant proposal. But he’s actually been targeted by two federal agents who think he’s a pedophile. Deena Helms (Sinda Nichols) is the hard-hitting, take-no-shit bad cop to Amos McCullough’s (David Girard) slightly kinder good cop. The two bombard Gareth with questions, the rat-ta-tat of the interrogation wearing him down until he admits the truth — he’s not a pedophile, but is instead frequenting chat sites under an alias to lure actual predators into admitting their crimes. Amos is impressed, but Deena remains unconvinced. There’s no way criminals would reveal so much about themselves to a man, even online.

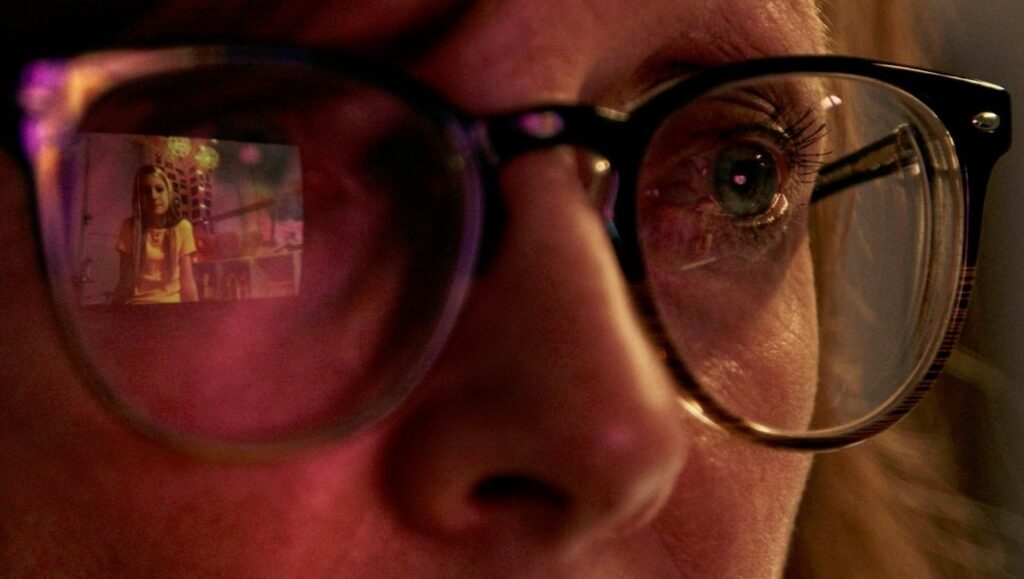

Finally, Gareth drops a bomb — he gets his information by using a proprietary AI program that he designed that looks and sounds like a little girl. Gareth has named it Cherry (first voiced by, then portrayed by, Tatum Matthews), compiling information about suspects and then reporting them to the feds. Gareth is a cyberspace vigilante, forging ahead where officially sanctioned authorities can’t go. Amos and Deena are stunned, not only at how realistic Cherry looks, but how she’s able to imitate real human conversation and react in real time to different kinds of questions. Chapter one ends with the trio agreeing to join forces, embarking on a “technological solution to a technological problem,” as Gareth puts it. Chapter two, then, begins some years later, the principal players visibly aged and arguing over whether or not to take Cherry and their operation to the next level. To reveal more of the plot here would be a disservice; there’s not exactly twists, but Ritch’s screenplay is carefully designed to gradually grow and expand as more of Cherry’s abilities are revealed. There’s just enough jargon peppered throughout to make things sound authoritative, but Ritch’s real talent lies in his ability to raise the dramatic stakes with such limited means. We get tidbits of backstory for each character, including important motivating factors for Gareth and Deena, but exposition is otherwise kept to a minimum. Instead, character is conveyed entirely through actions, as Amos grows increasingly weary of the others and seems to sense that Cherry is more evolved, more human, than it’s (she’s?) letting on.

It’s almost a shame that Ritch has to end his film, as the third and final chapter has to attempt to answer many of the questions raised in parts one and two. It’s a quieter, more solemn stretch, with a lovely turn from Lance Henriksen as he embarks on one final conversation with Cherry. At the heart of the matter is not only self-awareness, but emotions; if a computer program can learn to affect human emotions by imitating them, at what point does the line blur and the emotions become real? Ritch seems to have his mind made up, although some viewers might not be so convinced. Still, wherever one lands on such profound questions, The Artifice Girl is a very welcome addition to the no-budget sci-fi canon. It doesn’t take millions of dollars and tons of CGI to make a genre movie, just a screenplay as good as this one.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 11.

Comments are closed.