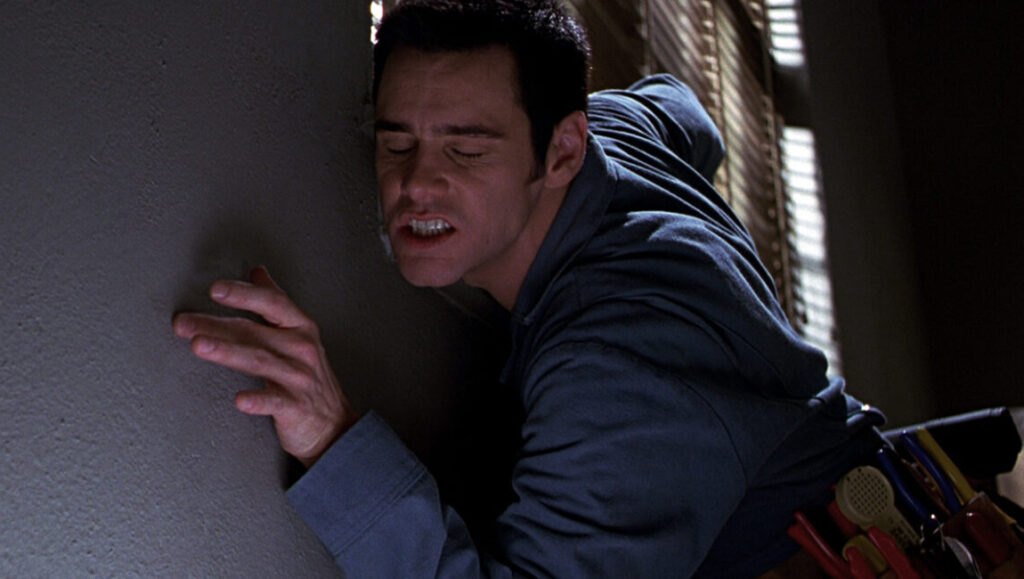

Though it’s not typically thought of as part of the Judd Apatow canon, The Cable Guy (which was co-written by an uncredited Apatow, who also produced, and directed by his friend Ben Stiller) nevertheless contains many of the same concerns of Apatow’s later comedies: grown men shaped (and warped) by pop culture, a great deal of anxiety about “growing up” and the role women play in that dynamic, and the ways in which male friendship offer a potentially destructive obstacle for that progression toward maturity. What makes it different is how the pop culture-loving heroes of Apatow’s later films are here represented as one certain crazed, and perhaps psychopathic, monster. Jim Carrey, at the peak of his nineties-era popularity, plays Chip, the titular cable guy hired by Steven Kovacs (Matthew Broderick), who recently moved out of his girlfriend’s place and into his own apartment. Chip somehow works his way into Steven’s life, as his unofficial best friend, and psychologically tortures the poor sap until he snaps. Much of the humor comes simply from Carrey acting ridiculous around other people; he’s tall, gangly, has a lisp, is unable to read social cues well, and is very clingy. He’s not autistic and he’s not gay — this is the rare bro comedy free of gay-panic jokes. His awkwardness is instead due to his complete inability to understand the world outside of television. His whole life is television — it’s the only thing he understands, and crucially, the only way he understands human relationships.

Much of the humor comes simply from Carrey acting ridiculous around other people; he’s tall, gangly, has a lisp, is unable to read social cues well, and is very clingy.

Chip is not so very far removed from the modern American male, who subsists on a media diet that at time makes him incapable of actually seeing how the world around him works. When Chip interrupts Steven’s pick-up basketball game by playing abnormally aggressive, or insists on dueling “to the death” at a Medieval Times restaurant (while simultaneously quoting Star Trek) he’s not just being goofy, he’s acting like how he’s seen people act on TV. And though the arc of Chip’s relationship with Steven is fairly conventional, the sheer lunacy of Chip’s actions and the increasing randomness of his references make this film one of Carrey’s finer outings and one of his few from the period that speak to the cultural moment in an interesting way. At the end, atop a giant satellite dish, Chip loses all anchor to reality and acts out an emotional climax to a police helicopter (which he believes is his mother, apparently), before flinging himself off a tower to break the dish (or, as he puts it, “kill the babysitter”). It’s ridiculous not only because we recognize these climactic beats (skewed as they are) from other, saner films, but because Chip doesn’t actually have a cathartic moment. He has no breakthrough. Instead, he’ll continue living through television (and, one imagines, eventually the Internet) for the rest of his life, whatever “life” means when you’re made up of nothing but references to other things.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.