Lorna’s Silence, the latest award-winning film from Belgian brothers Jean-Pierre and Luc Dardenne, begs discussion. Its unresolved ending tends to have a polarizing effect on both critics and audiences alike, leaving us guessing at both the fate of its protagonist and the filmmakers’ intent, not unlike the conclusions of John Sayles’s Limbo and the Coen brothers’ No Country for Old Men. There are myriad elements we could analyze and debate in this film (including the Dardenne brothers’ increasingly nuanced examinations of those marginalized in the European economic integration following the collapse of the Soviet system), but the inconsonant narrative form and incongruous ending of Lorna’s Silence deserve special attention.

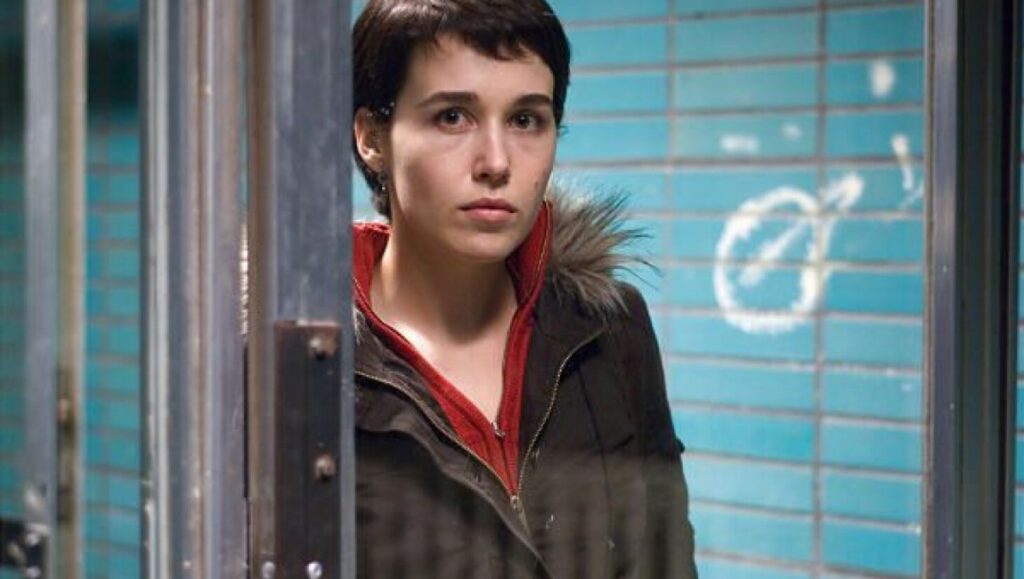

The first two acts, up until an offscreen murder, are the cinematic equivalent of a jigsaw puzzle: the film’s confounding and elliptical structure slowly introduces disparate elements of an ill-fated criminal scheme, and suggests lineage to the classic noir of half a century ago. And yet, this isn’t really a noir; the hand-held cinematography, the steady pacing and the absence of a soundtrack (a Dardenne signature) all form the antithesis of the moody black-and-white photography and taut suspense we expect from the noir genre. Lorna (Arta Dobroshi) and Sokol (Alban Ukaj), two Albanian immigrants with big dreams but little means, team up with Belgian mobsters in an elaborate double marriage scheme. Lorna first gains Belgian citizenship by marrying drug addict Claudy (Dardenne regular Jérémie Renier), and afterwards, the mob sells Lorna’s hand in marriage for a hefty sum to a Russian mafioso attempting to gain citizenship himself. Now, all that stands in the way of this mutual enrichment is Claudy, and the Russian won’t wait for a divorce, so Lorna must either find a way to save her husband or live with the responsibility of his death. Dobroshi’s portrayal of Lorna, a conscience-stricken woman unwillingly lead to a life of crime, is simultaneously impassioned and reserved — an especially impressive performance given the actress’ unfamiliarity with the French language (at the time of casting the only words of French she knew were the days of the week). With welcome restraint, Dobroshi communicates the contradictory nature of her character, eliciting both sympathy and revulsion. Renier is just as impressive, playing a character that is the complete opposite of the responsible family man in Olivier Assayas’ Summer Hours, and as Claudy, invoking empathy in even the most hard-hearted through his pitiful and tenacious pleas for help.

In noir, omissions of developments in the story are usually in service of creating suspense, but in Lorna’s Silence,” the use of a narrative ellipses seems metaphorical: the film’s structure mirrors Lorna’s confused mental state, and as we peel back the layers of the criminal plot Lorna is mired it, she herself comes to grips with her own conscience. It’s a daring marriage of form and content, and though it’s certainly not the first film to attempt something like this, it’s easily one of the most successful to do so. Even more audacious is the ending (or lack thereof, depending on who you ask): in a film like this, the criminal plans of the characters always fail, but what makes each of these films unique is how the characters react to that failure. Without giving anything away, Dobroshi’s performance is largely responsible for transforming Lorna’s Silence from an exercise in human cruelty into an altogether spiritual and surreal experience. The Dardenne brothers continue to examine the possibilities for the human spirit’s hope and redemption, while ultimately leaving interpretation of the conclusion entirely up to us.

Comments are closed.