For French director Gaspar Noe, life and death are not physical certainties but evolving psychological perspectives that often overlap. His three feature films (I Stand Alone, Irreversible, and Enter the Void) can be taken as one extended mosaic of prolonged suffering, a place populated by fringe characters constantly addressing hallucinatory crossroads. In Noe’s hyper-stylized universe, forms of extreme violence, flashes of color, and sexual debasement are hardcoded into the traditional value systems that ultimately come crashing down under the pressure of human infallibility. Both horror and beauty come from sudden shifts in point of view, upending characters’ preconceived ideas about love, loyalty, sacrifice, and protection. Instead of shortchanging this often extraordinary process with sentimentality, Noe dwells on the fluidity of mise-en-scene and sound design, the patterns of human disillusionment that push his characters ever farther down the rabbit hole.

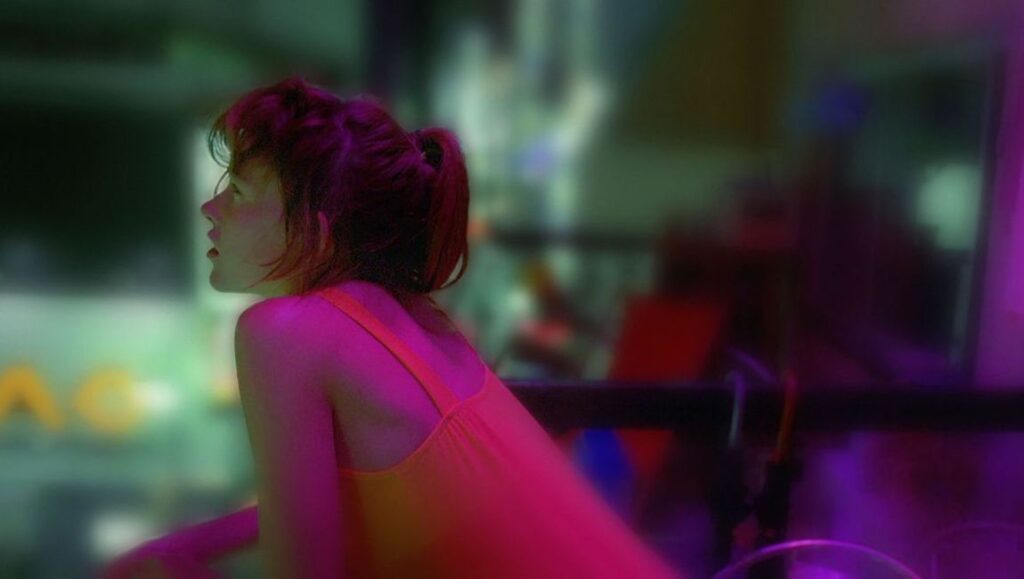

Enter the Void is foremost a haunted family album (mis)matching disintegrating memories with fragmented recreations. Its enthralling imagery and dense audible rhythms form a psychedelic head-trip into a crumbling first-person perspective experiencing sudden death and supernatural limbo. It may be loosely based on The Tibetan Book of the Dead, but it also feels deeply indebted to the confrontational cinema of Warhol and the flickering personal diaries of Brakhage. After a stampede of credits in multiple languages overwhelm the screen, Enter the Void begins in a small apartment where the camera stands in for the perspective of drug dealer Oscar (Nathaniel Brown) who watches his stripper sister Linda (Paz de la Huerta) prepare for the Tokyo nightlife bustling on the colorful streets below their balcony. Oscar smokes some heroin and descends into a hyperbolic state, witnessing Noe’s plumb cloud of colorful imagery both completely striking and altogether indulgent. As Noe holds on to the twisting and contorting hallucinations, something akin to a heightened screensaver running on a combustible engine, the film takes on a completely surreal focus. With this opening flashbang, Noe potently introduces the audience to his warped sense of visual splendor and mental fragility.

After coming down from his extreme high, Oscar meets up with Victor (Olly Alexander), and the two men walk through the dank streets of Tokyo. Noe’s camera transitions to a third-person perspective, watching as his characters traverse a candy land of neon signs, dark alleys, and seedy nightclubs. Moments later, when a drug deal goes bad, Oscar is shot and his soul evacuates his body, a thrilling cinematic transition that Noe creates using the same sort of kaleidoscope imagery as the initial drug scene. From here, Enter the Void takes on a completely immersive tone, Noe spending the duration of the film pummeling the viewer with flashbacks and flash-forwards charting Oscar’s difficult childhood, his descent into drug dealing and abuse, and finally the guilt he feels toward getting his baby sister hooked on the underground lifestyle. Noe’s camera, Oscar’s perception, and the audience’s patience all become intrinsically linked, and the break-neck experience becomes something altogether singular and ultimately frustrating.

As opposed to Irreversible, which unfolds backward after a life-altering moment of violence, Enter the Void hopscotches forward and backward, always depending on Oscar’s ghostly perception of the physical world. We can never truly trust what Noe presents us because the very basis for Enter the Void is the deconstruction of memory. Still, Oscar’s exaggerated trip down memory lane opens up Noe’s filmmaking, allowing the kinetic and frenzied movement of the camera to chart cliched cinematic experiences from new and fascinating vantage points. A sex scene between Linda and her boss suddenly becomes completely disturbing when Oscar’s ghost inhabits her body mid-coitus. Later, the terrible car crash that killed their parents stops mid-moment to reveal the last second of family life before impact. These types of astounding cinematic moments often come amidst endless sequences saturated with melodrama and self-importance, but amazingly Enter the Void stays grounded in some form of dynamic humanity for much of its first two acts.

By the time Oscar’s journey folds inward, becoming a quest for future truths as opposed to past traumas, Enter the Void turns into a self-indulgent mess. Noe takes the allusions and fantasies of The Tibetan Book of the Dead and transcribes them into literal symbols of reincarnation via an elaborate and prolonged sex sequence. Here, Noe digresses into sledgehammer cinema, pounding us with pulsating bodies, even more gyrating camera angles, and a final sex organ POV that is in hilarious bad taste. With this grandiose visual exclamation point, Noe not only confounds the brilliant flourishes of pain and heartache defining the early portions of his film, but also gives the audience more than enough reason to dismiss him as a blatant provocateur. Enter the Void is often an incredible example of cinematic possibility and ambition, a portrait of life and death as techno turntable spinning in and out of control with effortless precision. But its damning faults also prove Noe as a filmmaker obsessed with his own audacity, an artist unable to fully discern between poetry and convoluted artifice.

Comments are closed.