All one need do is look at the many and varied riches cinema had to offer in 2012 to disprove the crowing — yes, once again this year — from certain quarters about the “death of cinema.” Digital may be overtaking celluloid as the medium of choice for many filmmakers, but films like Ang Lee’s 3D spectacle Life of Pi demonstratethat, in the hands of real filmmakers, there are still plenty of visual wonders and expressive possibilities left to explore. Shooting on digital certainly didn’t stop imprisoned Iranian filmmaker Jafar Panahi from making one of the most heartbreaking and inspiring moral documents to grace movie screens this year, the subversively titled This Is Not a Film. And what of Alex Ross Perry and Paul Thomas Anderson, both of whom — with The Color Wheel and The Master, respectively — went back into movie history, using analog film (16mm in Perry’s case, 70mm in Anderson’s) to stylistically revisit the cinema of their forbears while forging ahead with their own distinctive visions? Maybe it’s fitting, then, that In Review Online’s best film of 2012 is a work that uses the digital medium to meditate on cinema’s past, present, and future. It’s a film that exudes a measure of skepticism toward cinema going forward, but that also revels in sheer creative freedom, suggesting that there’s no stopping an artist’s imagination, whatever the medium or budget. Kenji Fujishima

Note: As of the publication of this list, because it’s only in limited release, many staffers have not seen Zero Dark Thirty; the absence of Django Unchained, however, is reflective of our staff as a whole.

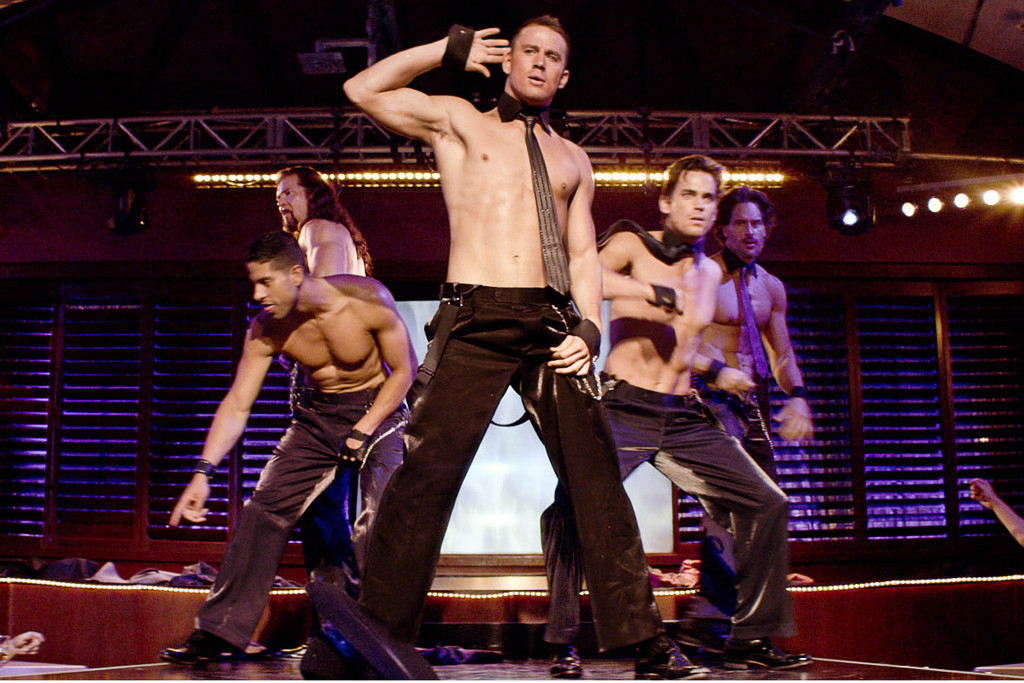

20. Steven Soderbergh turned out a better microcosm/critique of the Great Recession-era free market than Andrew Dominik’s Killing Them Softly, and without a single C-SPAN sound bite. His Trojan horse of a male-stripper movie shrewdly concealed its insights behind a patina of A-list flesh and then went further, exposing its own façade. Yet all that would have been for naught had the movie not offered such a bounty of surface pleasures: newly anointed box-office savior Channing Tatum reliving his semi-sordid past and giving his most effortlessly charismatic performance to date; Matthew McConaughey flipping his clean-cut image into a fearsome vision of sweaty, assless-chapped megalomania; and self-consciously performative dance sequences staged with all the verve of Golden Age musicals. The fantasy at the heart of Magic Mike — the idea that all you need to succeed in America is a dollar and a dream — was at once ridiculous and tantalizingly attainable. But we’re living in Soderbergh’s America, and in Soderbergh’s America, you’ve got to work/twerk. Alex Engquist

19. An introverted freshman dealing with mental illness and the recent suicide of his best friend finds himself constantly picked on by his peers as he starts his freshman year of high school. He ends up finding solace, however, in a small band of outcast seniors who take him under their wing. If this sounds like the set-up for any number of high-school coming-of-age movies, it’s anything but; Stephen Chbosky’s big-screen adaptation of his own best-selling 1999 novel, The Perks of Being a Wallflower distinguishes itself from the pack not only in its tenderly empathetic depth of feeling, but in the way it poignantly evokes main character Charlie’s desire to break out of his shell and finally experience the world, in all its joyous highs and crashing lows. Few moments in movies this year were as purely ecstatic as the sight of two of this film’s characters, at two separate moments, driving along a highway, drop top down, raising their arms to the sky and feeling a sense of freedom whooshing through them — a fleeting but precious moment to treasure for a lifetime. K.F.

18. The best way to approach Rick Alverson’s film is as a kind of perverse sketch-comedy anthology centering around an extreme version of a particular — and for some, strangely recognizable — type: the hipster douchebag who, perhaps as a result of his privileged upbringing, can’t help but take life as one big joke. Class issues, racial differences, religious beliefs, even others’ physical ailments: Swanson (Tim Heidecker) treats it all with an irreverence bordering on nihilistic contempt. Does he take anything seriously? The Comedy isn’t so much a serious analysis of this particular type as it is a kind of black-comic tap dance on the edge of an abyss, positing scenarios in which Swanson is presented with the potential to break through his persistent ironic veneer and forge an honest human connection. Whether he actually achieves such a breakthrough is for the viewer to determine; maybe irony is the only way he knows how to reach out to anyone. Along the way, The Comedy manages to conjure up an unexpected side effect: In navigating from one abrasive joke to the next, the film demands that viewers question their own connection to the world around them. K.F.

17. German filmmaker Christian Petzold impressed plenty of critics with 2009’s Jerichow, but even that fine work didn’t signal the the level of craft found in his latest film, Barbara — a paranoid thriller with the heart of a domestic drama. Set in the 1980s, Barbara is about a big-city doctor exiled to the provinces of East Germany after daring to apply for a Western visa. The film is steeped in the dread and uncertainty of the Iron Curtain era and anchored by Nina Hoss’s quiet, steely lead performance, while Petzold’s keen sense of time and place make Barbara a veritable masterclass in building suspense and genuine emotional heft, forgoing the quick cuts and jarring camerawork that’s become the hallmark of Hollywood thrillers. No one would mistake this electrifying, startlingly assured drama as anything but the work of a major filmmaker. Mattie Lucas

16. Forget the naysayers complaining about ‘yet another’ Jean-Pierre & Luc Dardenne movie; we direly need their brand of humanism right now. Devoid of religious platitudes, The Kid With a Bike instead presents itself as a parable of a kind of secular saintliness. Abandoned by his father with a brutal nonchalance, young Cyril (Thomas Doret) is sent to a boy’s home where he spends weekends with Samantha (Cécile De France), something like a foster parent. We’re never given a reason for Samantha’s devotion to this furious bundle of energy (as usual, the Dardennes eschew pat psychology), but she seems determined to care for this child regardless of the cost to her personal life. Cyril, meanwhile, spends much of his time with the titular bicycle, a gift from his father that he clings to obsessively, transferring all his familial devotion to it. Though Cyril gradually succumbs to the allure of criminal life, the Dardennes are less interested in suspense than in consequences, using a startling act of violence to condemn the cycle of retribution that seems at times ready to engulf us all. Deceptively simple, The Kid With a Bike quietly builds to a devastating climax — and an ultimately hopeful resolution. Daniel Gorman

15. Shot in purposefully drab black-and-white, the first few minutes of Girl Walk // All Day see an unnamed female dancer go through the motions of a classical-ballet routine. Suddenly, black-and-white becomes color, the female dancer snaps out of her creative doldrums, and Jacob Krupnick’s feature-length music video — set to the entirety of All Day, the latest album from a DJ with the alias Girl Talk — erupts into a joyous celebration of not only the creative spirit but also the possibility of forging connection in a potentially alienating urban environment such as New York City. Not that Girl Walk // All Day is all fun and games; most pointedly, the female dancer runs into an Occupy Wall Street rally, after having glammed herself up on a shopping spree, becoming the target of protesters’ jeers. But, light social commentary and all, Krupnick’s film exudes an unabashedly buoyant spirit that culminates in a large crowd in Central Park dancing to the strains of John Lennon’s “Imagine.” A more inspiring middle finger to cynicism is difficult to imagine. K.F.

14. Confined to a claustrophobic urban grid of a couple blocks in the seaside Brazilian town of Recife, Kleber Mendonça Filho’s impeccably crafted debut feature is a study of subtle atmosphere cantilevered over a sociometric melodrama. With sound design that breathes an ambience of fear, Neighboring Sounds holds the threat of violence in the balance right alongside the social schisms cultivated by family, race, class, and the burden of history. Trapped between the identity of his patriarchal grandfather, who built his wealth and subsequent power from a sugarcane plantation, and the self-absorbed persona of his delinquent younger cousin who breaks into cars for thrills, an apathetic yet enlightened median of his privileged middle-class family inhabits newly constructed apartment towers while an army of servants work to fulfill his and his families’ needs of protection and comfort. The co-dependent relationship between classes is pulled silently taut, as the tension manifests itself sublimely within the mundane trivia of everyday life. Filho deftly constructs a theorem of invisible cataclysm beneath progress and modernity, where a psyche-shaking nightmare still lurks behind a locked door, a locked gate, a guard dog, and a private-security crew. Kathie Smith

13. With Robert Zemeckis’s Flight positioning itself as the biggest Addict Film of 2012, Jaochim Trier‘s Oslo, August 31st has sadly been overlooked. Flight serves up a largely clichéd character — full of pride, anger, and denial — relying almost solely on its (admittedly fantastic) lead to convince an audience to overlook the facileness of the plotting. By contrast, Oslo unflinchingly fixes its gaze on a more fully developed protagonist, Anders (Anders Danielsen Lie), who’s fresh out of rehab and preparing for a job interview as the film opens. The trail Anders blazes for himself over the next 24 hours outlines the trajectory of this film, and is one that is honest and heartbreaking. As Anders struggles internally, his carefully manicured façade of impassivity and self-deprecating humor combating his unbalanced sensitivity and low self-esteem, the wellspring of ambiguity regarding his character only deepens our emotional investment. Ultimately, it’s as much Anders’ perceived superiority as his inferiority that shapes the character, leaving the audience to wonder whether he’s as much afflicted by the toll of living as he is by the power of addiction. Luke Gorham

12. Former film director Seongjun (Yu Junsang) comes to Seoul for a couple of days to visit a friend; after a tumultuous evening of drinking with a trio of strangers and showing up drunk on his ex-girlfriend’s doorstep, Seonjun finds himself trapped in a cinematic portal where he cycles through three finely drawn visions of fate, highlighted by the delicate shifts of mood he and his companions experience. Random things happen for no reason within the monotonous patterns of life, and South Korean auteur Hong Sang-soo has been studying these indiscriminate moments for more than 15 years. Shot in black and white, Hong’s The Day He Arrives packs the director’s familiar tropes — soju-soaked remorse and piercing, yet tender, satire — into a playful narrative of keenly observed possibilities. In nearly all of Hong’s films, the fragile hero is a film director of varying degrees of failure, and it is never too much of a stretch to consider them autobiographical characters. But this particular portrait is an especially self-deprecating confession of erratic and accidental perfection. K.S.

11. Misdirection is central to The Color Wheel’s appeal: The film’s drastic, last-act tonal shift is such a game-changer, emotionally speaking, that it could be enough to convert the otherwise unimpressed. That director/writer/co-star Alex Ross Perry — making only his second film, incredibly — can guide us so capably from improvisatory mumblecore witticisms to heartfelt, entirely deliberate histrionics is a testament to his gifts as both a comedian and a dramatist. And as a visual stylist, too; shot in black-and-white, on rich, grainy 16mm, The Color Wheel is the rare independent feature to not only embrace, but to relish a wistfully antiquated aesthetic. The results are as gorgeous as they are unique: As with his debut, the loose and offbeat Gravity’s Rainbow adaptation Impolex, Perry’s comic and dramatic sensibilities are very much his own, and whileThe Color Wheel’s abrasive style will no doubt alienate those not accustomed to its particular rhythms, those patient enough will be rewarded. Calum Marsh

10. In the year of “Big Data” and Nate Silver, the best film to speak to today’s world is a completely artificial one, David Cronenberg’s Cosmopolis, a work as radical as anything this director has made since Videodrome. A rip-roaring comedy about the psychology of data and capitalism, Cosmopolis takes us through the journey of a billionaire whose belief in digital patterns is questioned when he is unable to comprehend a disastrous fall in the yuan. In Cronenberg’s world, digital life is a cracking façade: monotonous dialogue pops like a screwball comedy, the limousine slowly deteriorates into a piece of junk, and our protagonist’s body physically corrodes in the most absurd of ways. Edited and shot with razor-sharp skill, Cronenberg’s adaptation of Don DeLillo’s novel might seem like the film the Occupy Wall Street movement has been waiting for, but it’s more of an attack on our constant investment in the signs, symbols, and patterns of digital life today. Two characters realize they both have asymmetrical prostates, and one demands to know its meaning. The response? “Nothing…a harmless variation.” The most unsettling thing in Cronenberg’s vision of the future is realizing that not everything can fit neatly into models. Peter Labuza

9. With its lush cinematography and somber tone, Nuri Bilge Ceylan’s slow-burn procedural Once Upon a Time in Anatolia is the Turkish director’s masterpiece, a culmination of his thematic interests all crystallized into a deeply melancholic examination of people who appear to be getting by, but who actually struggle with much inner turmoil, a lot of it spiritual. Ceylan paces his film deliberately and languidly, but Anatolia is by no means oblique; the plights of the characters are indicated much more explicitly than in, say, Antonioni’s films, which rely on a kind of emotional telepathy, or than in Tarkovsky’s, with their quiescent emanations of spirituality. In Anatolia, the main characters — a doctor, a police commissioner, a prosecutor, and a convict — are all subject to visions, memories, and monologues that make them question their place in the world, and their culpability as relating to a certain murder — whether that be finding the body, preparing it for autopsy, or completing the necessary paperwork. The film’s best quality is its reflective tone, which indulges characters existential crises, as their world cycles transiently from night to day. Tina Hassannia

8. Steven Spielberg’s audacious Lincoln is founded on the same principles of the final five minutes of A.I.: Artificial Intelligence: What appears to be a grandiose sentimental moment cunningly subsumes a devastating vision of political methods and consequence. Lincoln sees Spielberg’s formal technique employed in the most strategic way: sweeping camera movements and bold lighting beckon us into a mythic narrative of a hyper-conscious political moment, as the weight of history bears down on these characters in every scene. But screenwriter Tony Kushner invests us in the necessity of these political dealings, which include backroom agreements, semantic deceptions and, most abhorrently, putting lives in harm’s way for a belief in “history.” Even if the consequences are burning cities, bodies lying in the waste, and the assassination of an idol, Spielberg and Kushner create a vision of Hegelian history in which the rights of others are created by so many wrongs. With its emphasis on transcendence, every moment of awe-inspiring grace in Lincoln is undercut by questionable methods of politics. As Spielberg and Kushner provocatively suggest, however, that is the backbone of America. P.L.

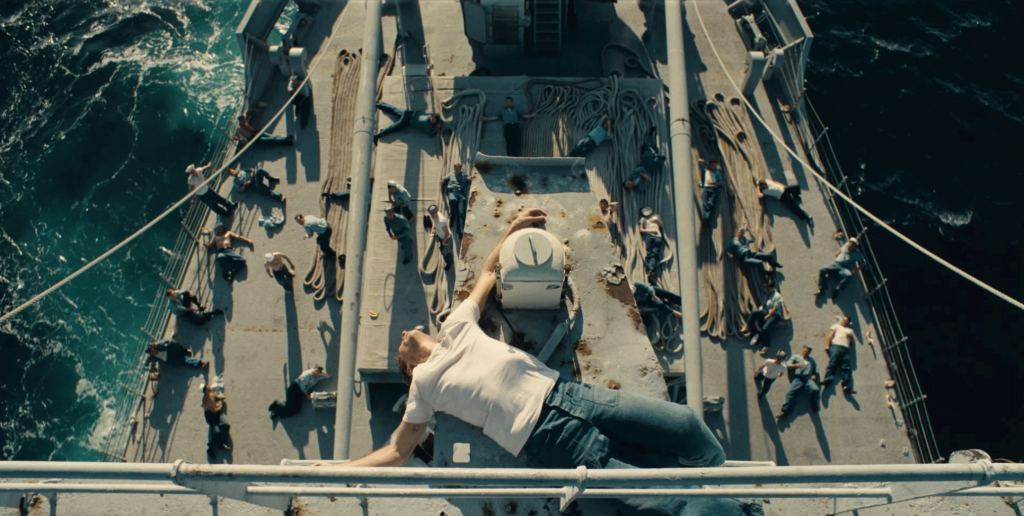

7. Frustrating as many viewers as it hypnotized, The Master is, like There Will Be Blood and Punch-Drunk Love before it, another one of Paul Thomas Anderson’s deep dives into interiority, a character study fueled by the roiling, unknowable, and often-bad tempers of its lead characters. The pace waxes and wanes, with long stretches of silence punctuated by loud, angry, often random and inscrutable outbursts. The meticulous visuals seem to alternate between placing tiny, vulnerable bodies against vast forbidding backdrops and imposing close-ups of troubled faces. For some, it’s a Rorschach test, ripe with potent context (post-WWII masculinity, alcoholism, Scientology) that, depending on who you talk to, either refuses to answer for itself or simply fails to cohere. Others see a romance of sorts, simply the story of two men who see themselves in one another. However one looks at the film, The Master, for all its formal control and narrative looseness, is at heart a simple film about the struggle to locate oneself in a scary world. Matt Lynch

6. As the old adage goes, when put in extraordinary circumstances, man will adapt, attempt survival, and often thrive under oppression. Life and art collide with grave consequence in Jafar Panahi’s This Is Not a Film, the oppressed Iranian iconoclast’s unthinkably resourceful docu-dispatch from his life under house arrest (which, to this day, continues unabated). Left to his own devices, yet with an inherent passion to create, Panahi transforms his apartment into a film set, literally outlining unrealized scenes from a future film of unknown fortune. Handcrafted on portable DVs and iPhones, from footage of Panahi’s day-to-day routine and his prior work under government sanction, this unclassifiable work of political and cinematic radicalism takes form, genre, aesthetic, mise en scène — even the roles between actor, producer, director, and distributor (lest we forget, this “film” was smuggled out of the country on a USB drive, hidden inside a cake) — and collapses the boundaries separating these considerations from our more privileged existences. A singular work of life during wartime, this is also the year’s most urgently undaunted film. Jordan Cronk

5. If The Turin Horse is indeed the great Hungarian filmmaker Bela Tarr’s final film, as he has stated numerous times, cinema will be the poorer for it. But this somber black-and-white dirge about hopelessness is a fitting note to go out on. Derived from a story by Nietzsche — of the writer’s encounter with a man viciously beating a horse that refused to move — Tarr imagines the fate of an animal, its cruel existence mirroring that of its owner, an enfeebled old man living with his grown daughter in destitution. Tarr films both unflinchingly, alternating fluid tracking shots that seem to go on forever and static compositions that emphasize a kind of existential stasis. Repetitions abound; routine is a crushing banality and even sustenance brings no joy, only life for another day. But there’s gallows humor here as well, and as well as sense that the entire world is contained in this film, through two entities in the throes of an uncaring universe. Tarr seems to be laying all the messy contradictions of life on the table here: He can’t go on, he goes on, forever; we can’t go on, and yet we do. The act of making art in and of itself constitutes a heroic struggle. D.G.

4. Forget The Artist, Michel Hazanavicius’s pale silent-film homage from last year; this year brought us Miguel Gomes’s mesmerizing Tabu, which restores faith that true silent cinema is not just some charming relic to be memorialized in Oscar-winning comedies. Spanning decades, Tabu weaves a tale of an elderly woman whose life has descended into a paranoid fog. A dying wish reveals a tale unknown to any of her friends or family — and allows Gomes to switch from sound to silent (save for ambient noise and a narrator who replaces dialogue or intertitles). The two sections of Tabu are completely distinct but also inseparable from one another, distilling love, aging, and Portugal’s colonialist past into a powerful statement. By turns absurdly funny and deeply moving, Tabu also caps off a banner year for black-and-white cinema, what with the achievements of both Béla Tarr’s The Turin Horse and Alex Ross Perry’s The Color Wheel. Gomes does simply repeat what has come before, either, but rather he stretches the boundaries of silent film into something thrilling and new, just like the great silent-era auteurs of yesteryear. M.L.

3. Little about his adaptations of Edith Wharton and John Kennedy Toole — which opted for guarded emotion and calculated stateliness — suggested the vision that Terence Davies would conjure up in tackling Terence Rattigan’s post-World War II play, The Deep Blue Sea. Here, Davies mounts an awakening of passion through a wonderful marriage of narrative and aesthetic — a testament to the filmmaker’s artistry and a bold affront to complacency. Not that Davies wholly abandon his auteurist signatures; his preoccupation with memory is organically and affectingly appended to the source material, thanks to some narrative tinkering, while his fondness for popular music makes for one of the most moving sequences in film this year. The credit isn’t quite Davies’s alone, though; Rachel Weisz also surprises, as a woman as possessed by her newfound conviction as she is a sense pf vulnerability. A more powerful combination of director and performer could not be found on movie screens in 2012. L.G.

2. The children in Wes Anderson’s movies are often more mature than the adults; the same is true in Moonrise Kingdom. Sam and Suzy, the central couple here, may be young, but their sense of alienation has given them insights to which the adults around them are oblivious. That gap in maturity and their love for each other are the engine that drives this movie’s conflicts. On one level, their obstacles are as small as anything children face, and yet the stakes feel enormous. Like Benjamin Britten’s The Young Person’s Guide to the Orchestra, which functions as the movie’s theme music even more than Alexandre Desplat’s score, Moonrise Kingdom is alternately playful and grandiose, rising to a dramatic crescendo that brings together all of its players. Community, even more than love or maturity, is the theme here; granted, this is also the key to Anderson’s entire oeuvre. Moonrise Kingdom, though, exercises this filmmaker’s talents with greater confidence than ever before, crafting a cinematic experience rich in humor, melancholy, and beauty. Andrew Welch

1. This year saw no shortage of thinkpieces on the death of film; whether defeated at the hands of cable television or lapsed cinephilia, movies were eulogized. Enter dormant French auteur Leos Carax — suddenly too busy making cinema to lament it — and his marvelous muse/avatar Denis Lavant. Allegedly cobbled together from a decade’s worth of abandoned projects, Holy Motors is episodic by design, so no surprise that so much praise has been heaped on individual sequences, like the accordion-jam entr’acte and the motion-capture pas de deux. But Holy Motors is greater than the sum of its parts; whether the elements presented are strange or familiar, Carax arranges them in such a way as to show us things we’ve never seen, but also reminds us why it is that we watch movies. Lavant makes Carax’s thesis thrillingly physical, through a journey of reinvention and self-destruction, greasepaint applied and removed. Dead or alive? Who cares! Let my baby ride. A.E.

Comments are closed.