Partway through Ex Machina, Caleb (Domnhall Gleeson), a mousy coder at a giant tech company, and Nathan, his supergenius employer (Oscar Isaac), discuss whether or not an alleged artificially intelligent android Nathan has created is sexually interested in Caleb. Nathan single-mindedly insists that the machine, named Ava (played by Alicia Vikander), and which he has designed to look and act like a human female, is fully capable of engaging in intercourse, and even says that you can’t have consciousness without sex. Caleb seems more concerned with whether or not Ava is actively flirting with him, or if Nathan has programmed Ava to do so.

Director Alex Garland seems far more interested in the gender politics associated with creating a fembot rather than any actual investigation of artificial intelligence or the responsibilities associated with technological innovation. But important data is missing. Aside from Caleb’s characterization as a “nice guy” (he asks Ava measured questions about how she feels, he’s attracted to her but respectful) and Nathan’s excessive dudebro demeanor (instantly but arbitrarily coding him as a jerk), we know materially nothing about the two human characters in the film. As for Ava, any reading depends on it being coded as female, when in fact it’s only an android, technically genderless.

the idea that true consciousness exists outside of rigidly defined ideas about bodies and gender, stays mostly unexplored

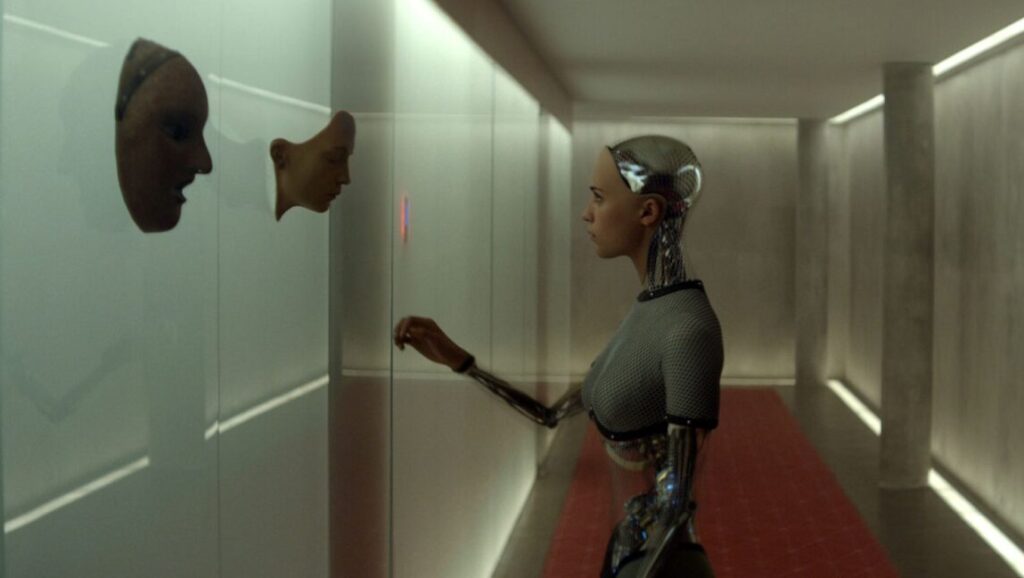

As Ex Machina plays out and eventually dissipates into a routine thriller, Ava turns the tables on “her” interrogators, and in doing so displays many of the criteria for true AI: reasoning, creative problem solving, self-awareness, empathy. She deploys her “feminine” skills to manipulate men who are either leering or condescending, preoccupied with male constructs of female sexuality. That’s all well and good, but Ava ultimately remains a fembot fatale of sorts, “characterized” only by the way in which sex is used as a weapon against her and how she in turn uses it for her own purposes. Even while she finally gains the upper hand, she remains a vaguely misogynistic genre construct, while the most fascinating and potentially progressive idea in the film, that true consciousness exists outside of rigidly defined ideas about bodies and gender, stays mostly unexplored.