Proof of the lasting influence of Gillo Pontecorvo’s 1966 docudrama The Battle of Algiers can be glimpsed in two relatively recent films making a sizable dent in last year’s new-release landscape: Ana DuVernay’s Selma and Clint Eastwood’s American Sniper. In Selma — as was the case with the film that is arguably its spiritual forerunner, Steven Spielberg’s Lincoln — there is an emphasis on political maneuvering, one that likens it to Pontecorvo’s film, with its independence-seeking revolutionary Algerians on one side and French-army authorities on the other. Eastwood’s biopic of legendary Iraq-war soldier Chris Kyle also bears at least some of Pontecorvo’s influence in the way it manages to exude sympathy for a particular side while still allowing for moral ambiguities to complicate that affiliation. In the same way that the famously conservative Eastwood evinces a sense of sorrow penetrating Kyle’s soul as the cost of his sharpshooter prowess, Pontecorvo is troubled by collateral damage wrought by the extraordinarily violent methods of the Algerians, even if he clearly sides with their cause.

But above all it’s Pontecorvo’s acute political and moral intelligence that distinguishes The Battle of Algiers, encapsulated not in any of the film’s tense action sequences and clearly articulated storytelling, but in a single music cue.

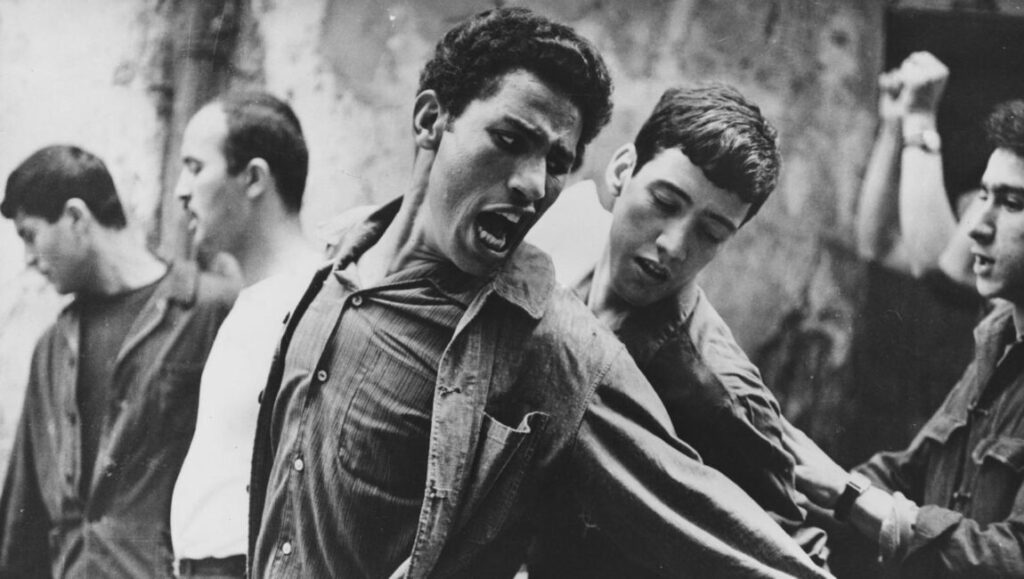

The gritty immediacy of cinematographer Marcello Gatti’s documentary style likewise remains relevant and impressive, giving viewers a genuinely immersive “you are there” feeling throughout (Paul Greengrass, this is how you do hand-held without making a major, headache-inducing point out of your jiggling camera). And though the cast of characters in Pontecorvo’s and Franco Solinas’s screenplay — most of them played by nonprofessional, local Algerians — are drawn in broad strokes, rarely is there a sense of these people as mere ciphers to score particular points. This is especially crucial in the case of Ali La Pointe (Brahim Haggiag), whom the film traces from his desperate beginnings as a discriminated-against street hustler to his political radicalization in prison and subsequent induction into the National Liberation Front (FLN) ranks. Even as he advocates for potentially appalling terroristic actions, we can’t help but remember where he came from and, thus, how it affects his views in the present. But above all it’s Pontecorvo’s acute political and moral intelligence that distinguishes The Battle of Algiers, encapsulated not in any of the film’s tense action sequences and clearly articulated storytelling, but in a single music cue. This first appears as the mournful accompaniment to the tragic aftermath of the bombing of an Algerian village at the hands of the French counterinsurgency — so far, so fitting. But then that same cue is repeated in the aftermath of similar terrorist attacks on innocent civilians perpetrated by the FLN. On Pontecorvo’s political playing field, there is no difference between who commits horrifying acts of extreme violence; a life lost is a life lost, plain and simple. And even as, in the film’s epilogue, we see and hear the battle cries of triumphant Algerians in 1962, celebrating their impending freedom from French occupation, The Battle of Algiers nevertheless leaves us on an ambiguous note, as the road to this supposedly heroic destination has been littered with reminders, both gruesomely physical and disturbingly psychological, of the worst of humanity. Judging by the past 10 years or so of U.S. foreign relations, there are lessons here we’ve all yet to learn.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.