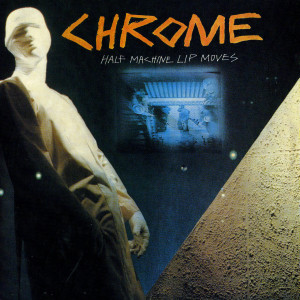

In an effort to reboot our music coverage, In Review Online is launching monthly features devoted to reviewing new album releases. The first of these features debuted on Wednesday. Today, we’re launching εὐδαιμονία (or, Eudaimonia), which we present in collaboration with the upcoming quarterly journal of the same name, and which will spotlight five worthwhile contemporary music releases, plus one older one, with no genre boundaries. Issue #1 features a new project from Atlanta rapper Future; albums from two electronic artists (Laurel Halo and Pariah); progressive metal band Deafheaven’s fourth studio album; a collaboration between jazz legend Charles Lloyd and alt-country luminary Lucinda Williams; and a retrospective review of experimental rock band Chrome’s 1979 album Half Machine Lip Moves.

εὐδαιμονία – New Music Releases

Arriving in the wake of a packed calendar month for new rap releases, Future’s oft-delayed sequel to his 2015 mixtape Beast Mode has been billed as the rapper’s seventh studio album (or ninth, if one counts collaborative releases What a Time to Be Alive and Super Slimey). Beast Mode 2 teams Future with frequent producer Zaytoven, exclusively — who also has co-writing credits on the entire album. The insularity of this project is practically unheard of, at least for modern rap releases of this scale, and it’s this intimacy that lends Future’s usual array of based sex anthems and lean-fueled degradation an elegance and grace that few of his peers and acolytes in the trap scene have accessed. Early highlight “Racks Blue” finds Future in ballad territory, crooning over Zay’s crystalline keys. The song‘s chorus runs through a list of possessions, all fairly standard must-haves for rappers in 2018: Patek, A.P. jewelry, etc. And yet the tenor of Future’s voice betrays a melancholy elaborated on in the hook: “What I’m supposed to do when these racks blue?” The question escapes as a pained moan, spilling Future’s conscience out onto the listener, conscripting us into his existential numbness. In doing this, Future undermines the rap genre’s tendency to celebrate brazen wealth, instead attributing his success to coincidence (“Comin’ from poverty, hittin’ the lottery”) and the guilt that comes with such a dramatic rise to success (“I know my heart belongs to the ghetto”).

Future is asking his audience to consider the full range of implications afforded his narrative and persona: Album opener “WiFi Lit” is a subdued banger that could soundtrack an MDMA-fueled night or a lonely evening spent contemplating one’s economic anxiety, while “Doh Doh” delivers on a more straightforward rap indulgence, with Young Scooter’s presence bringing out a hyped, carefree Future who gets to briefly revel in his clout sans the caveats that characterize the rest of this collection. Yet worry is never far from Future’s mind, and the album closes on a dour note with “I Hate the Real Me.” The man who once sneered “Bitch, I’ma choose the dirty over you, you know I ain’t scared to lose you!” pulls back and offers up bald proclamations of regret, presumably directed towards Ciara, the ex he cruelly slandered and cheated on. Zay provides a towering, piano-driven beat for Future to shout a loaded mantra over: “I’m tryna get as high as I can.” Chasing the fix provided by success and a coterie of drugs led him to sabotage a relationship that he sees as meaningful in hindsight, but the experiences that have colored his life make it so he can’t resist the temptation of excess. Beast Mode 2, as with most Future releases, plays as self-therapy, but not in a way that burdens the audience. Future invites us into his world as confidants, a trick pulled off via the the efficiency of his writing and its tonal deftness, and propped-up by Zay’s intuitive production. Future may hate the real him, but he’s never tried to hide that side of himself from anyone. M.G. Mailloux

Periodically, Deafheaven make forays into experimental territory, introducing elements of gothic balladry (“Night People,” a duet with Chelsea Wolfe) or slow, piano-heavy melodies (opener “You Without End”) or post-rock texture-building (“Near,” and how it gently bleeds into “Glint” before almost bursting from the sheer tenacity of its heavy guitars). Texture becomes a central source of tension on closer “Worthless Animal,” where lead guitarist Kerry McCoy’s elegant, reverb-heavy riffs contrast with Clarke’s vigorously animalistic cries. Even the thunderous drums can’t suppress McCoy’s rising chords, as chaos is slowly consumed by calming ocean waves. It’s an ending that feels both boldly audacious and intensely sincere for this group, who silence naysayers by continuously forging their own path outside the boundaries of trad-metal. And it’s moments like these that help elevate Ordinary Corrupt Human Love, making it more than simply a rehash of past work, but rather a step forward; a fresh, at times understated direction for metal’s most progressive act. Paul Attard

Laurel Halo’s three albums for Hyperdub are no exception; their non-linear architecture fixates on the construction of über-specific fragments that relate her work to a kind of anthropomorphic cubism (the jutting textures of Dust’s “Moontalk” sound like the aural equivalent of Picasso’s Girl With Mandolin). Her latest LP, Raw Silk Uncut Wood, was cut for the Paris-based label Latency, and plays, beguilingly, as a contemporary reimagining of futuristic avant-garde classics like Alice Coltrane’s Journey in Satchidananda. While previous Laurel Halo albums tended to resonate in a very introspective and grounded sense, Raw Silk Uncut Wood progresses outward to reflect on the unknown (as suggested by the alien-like image on its cover). The eponymous opening track is a sprawling, ten-minute piece that drops the listener into a study of timbres, introducing the album’s spectrum of pitch. The sonorous tones fade-out, and a stark image of extraterrestrial forces descending from space is summoned. The four short pieces that follow operate through a comparatively draconian logic — a constant flow of anxiety in search of safeguard. Finally, closing track “Nahbarkeit,” filled with low-end rumble, finds solid ground, transitioning the album from an out-of-body experience to a terrestrial state. The cumulative effect is a proclamation of limitless exploration and cathartic rest, and furthers Laurel Halo’s career-long ambitions. Patrick Devitt

Pariah’s latest project, Here from Where We Are — an ambient album from an artist not known for ambient music — must then be put to his own test. The exception here lies in the texture of “Seed Bank,” on which a shrill chirping dilutes the loop’s build of pitch, creating a sense of anxiety. Another point of disruption comes halfway through “Rain Soup,” as wind chimes suddenly begin to sound like swords in battle. A track like “At the Edge,” too, in its transition between synth pads, acts as a swampy, chthonic chasms before lifting back up into a pleasant numbness. That mold-breaking is not exactly ambient-as-ASMR as Spotify’s commissioning team would want, and it’s precisely the sound (or at least, the aural reasoning) that ambient artists will have to familiarize themselves with if they don’t want to prostrate themselves before our inevitable machine-learning DJs. M.A. Lucan

These Williams tracks (including the hymn-like album-closing cover of Jimi Hendrix’s “Angel”) are dispersed evenly throughout a program of Lloyd-led originals and covers that do their own fair bit of genre-bending. Lloyd’s take on “Ballad of the Sad Young Men” takes a torchy soul standard (with popular versions by Roberta Flack and later Rickie Lee Jones) and locates an innate proximity to lonesome cowboy blues, and this album’s rangy title track rejoices in a harmony between jazz improvisation and dexterous guitar soloing. On the latter track, Lloyd pitches some Sonny Rollins-worthy skronking down the middle to resolve the genre tension. But on Vanished Gardens’s unequivocal peak, a rework of Williams’s southern gothic dirge “Unsuffer Me” (off her unfairly maligned 2007 album West), the bleeding edge of the country singer’s serrated vocal meets the the horn player’s jagged bop over a scorchingly majestic 11:40 that approaches the fervent spiritualism of Coltrane and Ayler — or for that matter, Williams’s own epic Ghosts closer, “Faith and Grace.” The material featuring Williams here is the most exciting, and really deserves its own space (at 73 minutes, Gardens could have been a neatly organized double album, like Ghosts), but even wishing for that might be missing the point of an set that thematizes the grand communion at its center. Sam C. Mac

εὐδαιμονία – Retrospective Release

The song titles on Half Machine Lip Moves are culled straight from the sci-fi/cyberpunk repertoire. “Zombie Warfare” channels B-movie trash; “March of the Chrome Police” brings to mind Paul Verhoeven’s half-machine cop of New Detroit; and “TV as Eyes” elicits standard and enduring fears of technological surveillance. Then there’s “You’ve Been Duplicated,” a title that could easily pass for a lesser-known entry in Philip K. Dick’s vast oeuvre. Here the vocals are a menacing whisper, and the glee with which the not quite human-sounding vocalist hisses “You’ve been…replaced!” is enough to stand your hair on end. A few decades removed from the album’s release, finding ourselves now in an era in which reading the news is like skimming through a cyberpunk novel, Chrome’s rather evil sonic efforts resonate all the more alarmingly with each passing day. Chris Gisonny

Comments are closed.