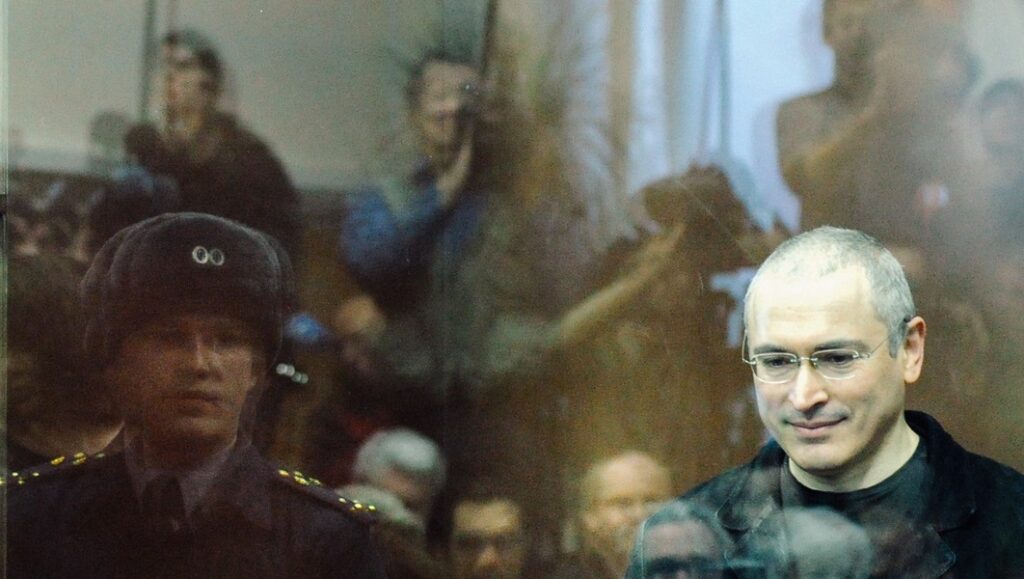

There was no way that we were going to escape the first four years of the Trump presidency without Alex Gibney making a documentary about one of its numerous scandals. Just as predictably perhaps, Gibney opts to turn his focus on the spectre of Vladimir Putin, whose approval of Trump’s election (and general shadiness) has, let’s just say, really captured the imagination of Liberal America. To Gibney’s credit, this new film, Citizen K, keeps discussion of Russian collusion off to the side and focuses more on mapping the rise of Putin and the implementation of his authoritarian control over Russian media and communication. His entry point into this narrative is through Mikhail Khodorkovsky, one of the Russian oligarchs who amassed tremendous wealth by exploiting the chaos and poverty brought on by the collapse of the Soviet Union and subsequently guided Russia’s transition to democracy and a privatized economic system from behind the scenes. By the time GIbney begins interviewing Khodorkovsky, the billionaire has found himself exiled by Putin, who was initially installed as president of Russia to serve the interests of Khodorovsky and his fellow oligarchs, before he outmaneuvered them so as to better consolidate his hold over Russian society, and weaponized the media against them.

This is all mapped out quite nicely within the film’s first hour in a way that often resembles the mode of the political history narrativizing employed by Adam Curtis, and for a time Citizen K is a useful text, illuminating an important stretch of recent history that your average non-Russian will only have a vague comprehension of. But then the second hour comes around and Gibney opts to refocus the film, turning it into a chronicle of Khodorovsky’s present day life in London, which he spends funding and promoting efforts to oust Putin from office. At this point the film begins to heavily rely upon talking head interviews with Khodorovsky and more or less cedes the pulpit to his agenda, accepting the narrative that this man who once preyed upon the misfortune of the Russian populace eventually realized the error of his ways and now combats Putin’s government as a redemptive act. This isn’t to say that Putin shouldn’t be scrutinized, but that Khodorovsky is complicit, and that Gibney is all too willing to accept the altruistic front the oligarch presents. Documentarians operating in the political world inevitably come up against controversial figures, even ideologically toxic ones (Errol Morris countless times, Laura Poitras with Risk), but Gibney rarely pushes back on Khodorovsky, admitting that many Russians distrust him for his corruption with a sort of shrug before bringing the movie to a close. This film’s subject could be approached in an enlightened, balanced way, one that locates the distress of living in a modern moment, when it’s hard to ignore the fact that nearly no one with significant political agency has the citizenry’s best interests at heart. But, alas, Gibney opts instead for a stance that passively endorses the xenophobic “Russia Gate” fear mongering that has been dominating our news cycles for far too long.

Published as part of Toronto International Film Festival 2019 | Dispatch 4.

Comments are closed.