The Best Is Yet to Come

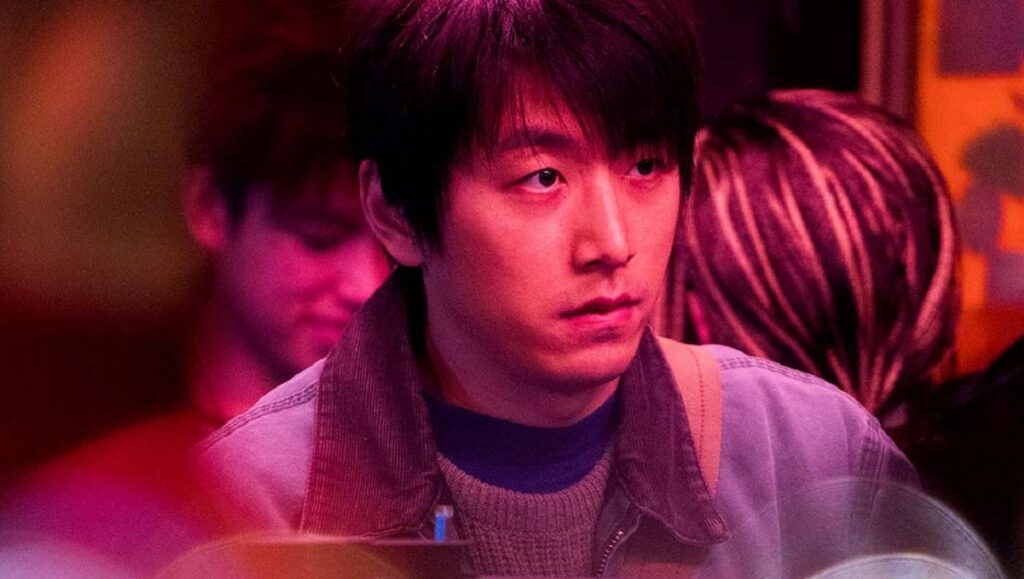

Think Spotlight but shot by Yu Lik-wai, Jia Zhang-ke’s favorite DP. Sounds pretty neat, right? And for a while, The Best Is Yet to Come is an involving, topical newsroom drama: Wang Jing zips through the early, procedural-minded portion of his feature directorial debut, meshing the documentary influences of its producer (Jia, naturally) with the polish and scope of a bigger studio picture. The setting is 2003 Beijing: An amateur journalist and high school dropout, Han Dong (Bai Ke), migrates to the city with his girlfriend, Xiao Zhu (Miao Miao), both of them leaving behind unfulfilling lives at a factory. Han Dong has little luck landing a job in the city with his lack of credentials and educational background, but he eventually lucks into an internship at one of Beijing’s bigger papers, the Jingcheng Times. Successes on his first few assignments get Han Dong a foothold on the investigative reporter beat — and then he finds his front-page scoop, the existence of an illegal network facilitating fraudulent blood tests.

The Best Is Yet to Come also has some shades of Zodiac, if only for the earnest/grizzled dynamic shared between Han Dong and his superior, jaded veteran journalist Huang (Zhang Songwen, fresh off his role in China’s mega-popular procedural TV show The Bad Kids from earlier this year). It was Huang that recommended Han Dong for his internship, perceiving a talent for nuts-and-bolts reporting as well as an attentiveness to telling individuals’ stories, and it’s Huang who Han Dong eventually finds himself at loggerheads with in this film’s latter third. That disagreement also forms the moral and ethical crux of the film — as well as its refreshingly critical attitude toward governance in 21st century China. Specifically, Han Dong’s attitude toward his big-break story evolves: It turns out that the forged blood tests are a best-hope scenario for those that had Hepatitis-B during a time when China’s understanding of the disease was informed by lingering paranoia from the SARS epidemic and generally unfounded science, leading to a prohibition on hiring Hep-B positive people or allowing them into universities.

It’s at this point — when The Best Is Yet to Come finds its narrative and political purpose — that the film unfortunately settles into being a rather more staid and emotionally hokey message-movie, even while it also continues to shift focus on a whim to Han Dong’s romantic life with Xiao Zhu, who has almost no defining characteristics of her own (another similarity to Zodiac) aside from her tireless support for her boyfriend. There are also two really egregious surreal/fantasy moments involving flying CG pens and newspapers that contribute nothing and simply feel ported in from a much less serious-minded movie. And, as a leading man, Bai Ke — apparently a social media star, not an actor — is frustratingly blank (one more Zodiac similarity for the road). Despite all that, there’s plenty here that works, from Zhang’s acerbic, fast-talking performance to Wong’s often-affecting incorporation of extra-narrative testimonials from Hep-B positive people telling of their struggles to navigate life as social pariahs. And then there’s the estimable Yu Lik-wai on hand, of course, and his work here is way more compositionally striking and visually dynamic than this ever needed. Given a more streamlined screenplay, and maybe the firing of a special effects tech, Wong and Yu probably could have laid-out Spotlight and the plurality of similar films that have cropped up in its wake; thankfully, I hear that they have some better stuff coming… Sam C. Mac

Quo Vadis, Aida?

The spectre of doom looms over the besieged town of Srebrenica for the entirety of Jasmila Žbanić’s Quo Vadis, Aida?, but the portended massacre only occurs towards its end, summed up in just a handful of shots. And all the better for the film — even before the breakout of actual shelling and gunfire, fear, anxiety, desperation, hopelessness, anger, and confusion hang palpably in the air. In any conflict, such tensions are present at every level of command. And in any conflict, the first to succumb are its people.

Žbanić’s sixth feature deftly weaves these oft-disparate threads into an intricate yet urgently harrowing narrative that firmly rebukes the fetishization of war and violence as simply litanies of unknown, unseen agents fighting over territorial abstractions. Days before the Serbian army overruns the United Nations base in Srebrenica and forcibly coerces the thousands of Bosnian civilian refugees out, the UN peacekeepers navigate a threefold crisis: resolving the logistical constraints of housing the refugees and admitting many more, negotiating with the clearly mightier Serbs, and contending with radio silence from unseen superiors who don’t have the political courage to decisively counter any military aggression. At the epicenter of these developments is Aida, a Bosnian interpreter whose primary role is to communicate information from the peacekeepers to the civilians. But as negotiations crumble in favour of the enemy and incoming hordes of refugees clamour to enter the base, she faces increasing strain as she delivers empty promises to an unbelieving audience.

A muted anger pervades Quo Vadis, Aida?, not just towards the brazen criminal injustices undertaken in broad daylight but also against the sheer helplessness of its victims and their supposed guardians. The UN finds its political backbone systematically bent and broken by the swaggering Ratko Mladic, kingmaker and mastermind behind the eventual genocide; the organization’s walls are painfully and inevitably breached. Aida, whose family waits outside the base, has to fight for them the same privileges she is accorded — while doing so constitutes a breach of her professional duties, who is anyone to judge her personally as a wife and mother, and who is to act on her behalf? By situating our gaze on Aida throughout, Žbanić draws us into a frenetic and nauseating losing battle, in which survival alone makes for victory. In the face of inaction, her fraught desperation and often selfish actions can only be read as heroism; the abstraction of mass atrocities may only demand from individuals a single response to the query “Quo vadis?”: my family, my people. Morris Yang

Another Round

The 19th-century French poet, Charles Baudelaire once wrote, “You have to be always drunk. That’s all there is to it — it’s the only way.” For Baudelaire, the notion of drunkenness is something mysterious, unearthly, and as he suggests, one has to be continually drunk “so as not to feel the horrible burden of time.” This Baudelairean concept accurately provides insight into what the well-known Danish filmmaker Thomas Vinterberg aims for on different levels with his latest effort, Another Round (originally titled Druk, which roughly translates as “heavy drinking”). The film depicts the story of four middle-aged friends and high school teachers who are each struggling with professional and domestic midlife crises. One night, they decide to secretly put into practice a hypothesis by Norwegian philosopher and psychiatrist, Finn Skårderud: that it’s sensible to be continually drunk if one can steadily maintain a 0.05% BAC! For the male quartet, this decision doesn’t just turn into an act of resistance, a way of evincing their courage and self-confidence in the face of their personal difficulties, but it also becomes a relentless quest for them to regain their lost youth, libidinal desires, and unfulfilled dreams. In this way, Another Round resonates with Vinterberg’s other works, which likewise study the relationship between society and the individual, where deeply rooted customary (mis)behaviors and habits gradually begin to reveal their dark and destructive effects.

Here, what’s distinctive in Vinterberg’s aesthetic approach is that although he still utilizes some stylistic trademarks of Dogme 95 (for instance, hand-held camera and natural lighting), the film feels cozier, more gentle and less acerbic. These qualities lend the film an atmosphere of tragicomedy, as Vinterberg frequently injects doses of socio-political satire, such as with a playful interlude including archival footage of drunken politicians. Another Round also sees the reunion of the director and star Mads Mikkelsen (in the main role of Martin, the history teacher) eight years after their acclaimed collaboration in The Hunt, and as usual, Mikkelsen’s reliable presence anchors much of the film even if it’s largely the efforts of the ensemble that give Another Round its most vital energy. Vinterberg supports the film’s heavy character work through his ability to create an immersive mood or situation, integrating several impactful musical pieces, extracting poignancy throughout.

Still, Another Round has its share of deficiencies: though Vinterberg manages to generate some dramatic suspense, the straightforward narrative is at times predictable and didactic. But if there’s a more crucial problem, it’s that Vinterberg, like his characters, is far too fascinated with the film’s one idea, which he insists on playing out over and over — more forcefully and loudly each time, as if to make sure the audience doesn’t miss the point. As a result, some of the dramatic tension and the specifics of the many irresponsible behaviors come across as dubious, unconvincing in their clear artifice, and more-or-less abstracted from any concrete reality — even when we hear Martin’s wife Trine (Maria Bonnevie) say, “This entire country drinks like maniacs.”

But if Vinterberg seems to shows his hand throughout the entire film, he still manages to save his trump card for the end: Another Round’s bittersweet final scene isn’t just one of the year’s most memorable endings, but it’s also where both Vinterberg and Mikkelsen realize their full potential. The same can’t be said for the rest of the film, but if there’s one thing that perfectly reflects the overall experience of Another Round, it’s to be found in the final still-shot of Mikkelsen’s Martin, suspended somewhere between thrill and disappointment. He’s a man (and it, a film) fixed between soaring and sinking. It’s a feeling viewers will likely share at film’s end. Ayeen Forootan

Spring Blossom

Part of the official selection at this year’s Cannes Film Festival that never was, Spring Blossom sees Suzanne Lindon, daughter of renowned French actors Vincent Lindon and Sandrine Kiberlain, direct and star in a debut feature about first love. The story revolves around Suzanne (Suzanne Lindon), a sixteen-year-old who longs for more stimulating interaction than she gets from her hedonistic peers, and duly grasps her opportunity when she encounters an older actor named Raphael (Arnaud Valois), whose play has arrived at the local theatre. Although the central relationship here might remind one of Call Me By Your Name, and is in many ways as bourgeois as that film, there’s little that feels passionate or vital about this particular adolescent experience; Suzanne’s infatuation is confined to longing gazes, displays of naivety, and other overfamiliar markers of awkward innocence. Lindon herself is a fresh, unconventional on-screen presence, yet the romance of sorts between the mutually bored couple lacks any dynamism; their exchanges of dialogue are largely mundane and unrevealing. As a portrait of Suzanne’s burgeoning sexuality, Spring Blossom is hardly subtle, but Lindon’s canny direction is frequently distinctive, replete with idiosyncratic flourishes such as when Suzanne and Raphael inexplicably burst into a synchronized dance routine while seated at a cafe. While her use of music to instill mood is at times impulsive, Lindon’s choices are eclectic and appropriate enough, avoiding the distracting, jukebox-style pop songs favored by filmmakers in the early stages of their career (or most of it, in the case of Xavier Dolan). There’s an appealing use of a French version of Frankie Valli’s “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You,” while the titular composition “Spring Blossom” (an original work by Vincent Delerm), makes for a rather lovely motif throughout. Despite France’s low age of consent, the principal characters’ understanding of boundaries helps prevent the romance from feeling too creepy, so it’s a shame that Spring Blossom does feel under-realized on the whole. As Lindon’s first cinematic offering, however, it leaves you somewhat enamored by her individual authorial voice and curious to discover where this fledgling filmmaker’s career is heading. Calum Reed

76 Days

There’s a harrowing sense of immediacy to Hao Wu and Weixi Chen‘s new documentary, 76 Days, which provides a fly-on-the-wall look at the early response to COVID-19 in a Wuhan hospital. It may seem awfully soon for a film about an ongoing crisis, but this film is the kind of indispensable historical document that could one day be viewed as one of the essential texts of the era.

Set in what is essentially ground zero for the novel coronavirus pandemic, 76 Days follows a group of doctors and nurses (all anonymously clad in head-to-toe PPE) as they deal with overwhelming demand, dying patients, and a virus unlike anything they’ve ever seen. Shot in jittery verité-style, the film is often unsettled and on edge, which creates a palpable sense of uncertainty around its subjects. The filmmakers try their best to draw out narratives from the chaos — an elderly man’s constant escape attempts, a young couple’s yearning to see their newborn baby born in the middle of the outbreak — but 76 Days is at its best when it isn’t trying to sift through the footage to create identifiable arcs for its disparate characters. What really sticks are the quiet moments: nurses looking for small moments of respite, a mountain of cell phones from dead patients waiting on a nurse to sort through them, the matter-of-fact informing of families whose loved ones have passed away.

Yet what is perhaps most striking about 76 Days is the stark contrast between the Chinese response to the coronavirus and that of the United States, where rugged individualism and an incompetent president have prolonged the pandemic far beyond the original deadly outbreak in Wuhan. When the lockdown is finally lifted in April of 2020 after 76 days, it’s a moment of catharsis, a catharsis that has as of yet been denied to the United States, which has done very little to contain the spread of COVID-19 while Wuhan has mostly returned to normal. And so, while the documentary stays hyper-focused on the response in a single hospital in Wuhan, it is the dichotomy between the US and Chinese responses that, at least for this American critic, was ultimately hardest to shake. That so many Chinese put their lives on hold for the greater good, while so many Americans continue to childishly protest the inconvenience of wearing a mask in public, makes our national response look like a colossal failure. While the rhythms of 76 Days are occasionally uneven, its immediacy never wanes, offering a frayed, fractured, and fascinating glimpse into the very heart of one of the defining crises of our time. Mattie Lucas

Comments are closed.