In the Same Breath

For a while, Nanfu Wang’s In the Same Breath makes for a fascinating companion piece to Ai Weiwei’s 2020 documentary CoroNation. Neither director has been shy with their criticisms of the Chinese government, and so it’s immediately fascinating to see how their approaches to a shared topic — the Chinese government’s response to the initial Covid crisis in Wuhan and subsequent manipulation of the official narrative for propagandist purposes — take different shapes. Ai’s work, culled from nearly 700 hours of mostly amateur, surreptitiously shot footage, opens as a dystopic mood piece, capturing the eerie silence of the pandemic’s early days, before shifting into a few elongated, intimate sketches of procedural minutiae and suffering. He relies heavily on mood and repetition — both in his selection of imagery and in his method of stitching together unrelated but startlingly similar footage — to build an unsettling and often surreal look at the insidious power structures behind China’s crisis response. Taking a different tack, In the Same Breath, for a while, holds the posture of investigative journalism, weaving conspiratorial yarn from an assemblage of personal anecdotes, official state reportage via sanctioned news outlets, and a lot of dot-connecting.

But then Wang shifts gears, moving her film westward and assessing the United States’ national Covid response. She carefully cycles through a few key bullet points — the punitive approach toward whistleblowing, the lingering trauma of frontline healthcare workers who witnessed death on such a mass scale, the validity of Covid truther concerns amidst such widespread, state-mandated misinformation campaigns — but the thread of her thesis begins to fray. This section evinces an intellectual looseness that becomes difficult to fully get behind; there’s no denying the power generated by allowing nurses to speak to their own horrific experiences, but Wang’s attempts to lend legitimacy to the objections of the haircut mob are undercut by setting such arguments to footage of liberty-or-death hordes — one Einstein informs the camera that his mask is located under his scrotum.

These discursive asides eventually come full circle when Wang shifts her focus back to China in order to reinforce the mirroring at play, but her argument that neither democratic nor authoritarian institutions have the moral high ground in the face of such human collateral isn’t all that cutting, particularly in a post-Trump world where the fetishization of national exceptionalism has become a global talking point. That’s not to deny the force of most of what’s presented on screen here: both visually — a bird’s eye view of a Chinese cemetery, shot as an aerial cam zooms out and the footprint of death expands, is a particular gut-shot — and empathetically — nothing in Ai’s documentary approaches the image of a father attempting to give his dying son water as a doctor tries to evict him from the hospital room — but Wang would have done well to rein in her instinct toward pat dialectics. It’s unlucky for Wang that her film followed CoroNation, and in some ways, their relationship speaks to our experience of the pandemic. Ai’s film chillingly captures the shifting, unsettling mystery of early Covid days, riffing on our fear of the unknown, its aesthetic a tapestry of impressionistic touches. In the Same Breath feels like the later-days take that it is, heavily rhetorical and somewhat sapped of energy, angling for conclusive assessment but fumbling in its attempt to weave its disparate threads.

Writer: Luke Gorham

Summer of Soul

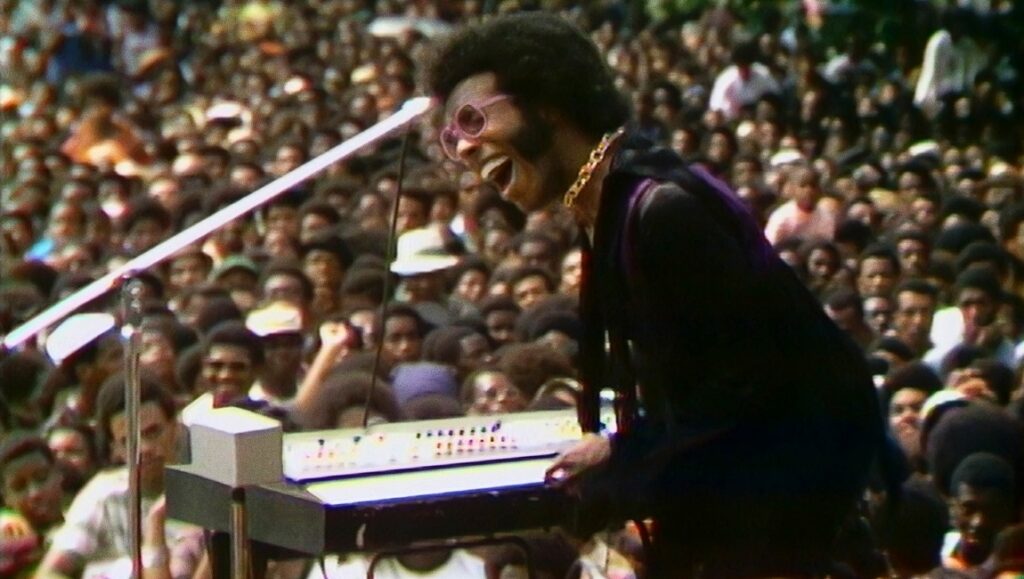

Ahmir “Questlove” Thompson, drummer of the legendary hip-hop band the Roots, besides his many other talents, is a music historian and professional DJ. Thompson deftly puts both of these skills to work in his debut feature, the alternately exhilarating and infuriating documentary Summer of Soul (… Or, When the Revolution Could Not Be Televised), which compellingly excavates the long hidden and nearly forgotten story of the Harlem Cultural Festival, a series of free concerts held over six weekends in the summer of 1969 in Harlem’s Mount Morris Park (now named Marcus Garvey Park). The concerts were attended by about 300,000 people and featured an insanely impressive lineup of acts: Stevie Wonder, Sly and the Family Stone, Gladys Knight and the Pips, Nina Simone, the Staples Singers, David Ruffin, B.B. King, the Fifth Dimension, the Edwin Hawkins Singers, Mahalia Jackson, and Max Roach, among many others.

Summer of Soul is, in part, a tale of two monumental cultural events. At around the same time the Harlem Cultural Festival was happening, the Woodstock festival — which we should remember featured precious few Black performers — was being held a few hundred miles upstate. While Woodstock has been endlessly celebrated and mythologized — and here’s where the infuriating bit comes in — the Harlem Cultural Festival has been almost completely neglected in memory, its beautifully shot footage, by the late Hal Tulchin, sitting unseen in a basement for 50 years after he could find no buyers interested in turning his footage into a finished film. Tulchin, in equal parts savvy marketing and desperation, dubbed the event “the Black Woodstock,” but to no avail. In the words of one of the film’s subjects: “We hold these truths to be self-evident, that Black history will be erased.”

Thompson puts his skills as a DJ and musical curator to great use in Summer of Soul, his unerring instinct successful at finding resonant moments from the concerts. One example is an early scene in which a boundlessly energetic Stevie Wonder — then just 19, only a few years away from beginning his incredible run of ’70s album masterpieces — pounds out a funky riff on his keyboard and then steps behind the drum kit for a jaw-dropping display. Another scene that will absolutely delivers the chills is Mahalia Jackson and Mavis Staples teaming up to deliver a fiery yet delicately tender rendition of “Take My Hand, Precious Lord,” reportedly Martin Luther King, Jr.’s favorite song, one he requested right before he was assassinated.

Thompson, for this part, expertly weaves in reminiscences among the concert clips, capturing the words of both performers and attendees, while also ably explicating the turbulent sociopolitical context surrounding the concert, which coincided with a major shift in Black people’s consciousness at the time and reflected more radical politics coming to the fore. To paraphrase one of the film’s interviewees, this was the period during which the Negro died and Black was born. In a scene near the film’s conclusion, Nina Simone, while reading a poem, asks from the stage, “Are you ready, Black people?” After viewing this powerful film, one defined both by its outrage and its joy, the only logical answer, and not just from Black people, is a resounding yes.

Writer: Christopher Bourne

Night of the Kings

Storytelling is at the crux of Philippe Lacôte’s entrancing sophomore feature, whose structural integrity depends upon a viewer’s willingness to accept its dramatic reflexivity. A mythopoetic work invoking the oral tradition of One Thousand and One Nights, and utilizing a Scheherazade-like figure as its bardic messenger, Night of the Kings intriguingly — and not ineffectively — infuses sociopolitical reality into a canvas of magical fantasy. This hybridization produces an atmosphere that’s at once earnest and self-aware — though the film as a whole is best described as theatrical cinema. This theatricality informs the political struggles taking place within the forbidding MACA prison of Côte d’Ivoire, where most of the film is set, and allows them to play out as literally as possible without the distractions of personal, anal-retentive intricacies.

An unnamed young man (Kone Bakary) is thrust into the raucous and chaotic MACA, and before he can overcome his initial disorientation he is singled out by the prison’s Dangôro (or supreme master) for the role of “Roman,” or storyteller. The occasion is a night when the moon turns red and Roman — a play on the French word for “novel” — will deliver a tale on prison grounds, in a ritual that signifies the end of the Dangôro’s reign and his naming of a successor. As the film’s opening intertitles reveal, the prison is “a world with its own codes and laws,” and this ritual, wherein the prisoners accept and perform their assigned roles without question, embodies tradition proper. Both political and narrative traditions, as it turns out: the former insofar as a sovereign hierarchy is upheld even through power successions, the latter via the act of storytelling as well as Lacôte’s stagelike presentation of it.

The rich tapestry of narrative threads interwoven within Night of the Kings transforms the concrete brutalism of MACA into a heightened and immersive communal space, celebrating the kineticism of bodies and words as they convey histories and fantasies both ancient and contemporary. As with Scheherazade, Roman’s fate depends on his ability to spin a tale past the morning sun, failing which he would be sacrificed. He gesticulates and orates on the life of Zama King, both an infamous Abidjan street bandit and an inhabitant of a mythical African kingdom. There’s an element of caricature to these stories, but Lacôte choreographs them impeccably and clearly elucidates his metafictional thesis on the promises such stories hold for the human imagination. It is enthralling to see Bakary, who plays Roman, having to improvise and expand on an elaborate palimpsest of Ivorian politics, youth disenfranchisement, and ancient mythology, not unlike the chameleon-like Denis Lavant who incidentally cameos as an inmate and advises Roman on the perils of concluding his tale. Lacôte’s title, likewise, is two-fold: there is the king who rules via the body politic, and the king who does so with words.

Writer: Morris Yang

Ailey

On December 4, 1988, dancer-choreographer Alvin Ailey received the Kennedy Center Honor in recognition of his contributions to modern dance throughout the second half of the 20th century. Almost a year later to the day, the performing arts world would mourn the loss of this visionary and vitalizing force, his lifework ceded to the interpretive whims of future creatives. Arriving close to what would’ve been Ailey’s 90th birthday, Ailey, Jamila Wignot’s moving tribute to his accomplishments and the dance company he founded, draws from a veritable collection of archival sources that ease us into recesses often inhabited by genius.

His story begins amid the sunkissed plains and cotton fields of Depression-era Texas. Ailey’s narration ambles through the worship sessions that defined his early affinity for gospel blues and spirituals, his beleaguered mother’s efforts to provide for the both of them, and a brush with death narrowly avoided by the intervention of his close friend, Chauncey Green. Alongside the thankless rounds of labor that are daily endured by those in Ailey’s hometown also exists a sense of care and convivial warmth. “It was a time where people didn’t have much, but they had each other,” he recounts, set to black-and-white footage of merrymaking. Gradually, this trancelike recreation is disturbed by smears of grain and particulate gathering over the images, blotting out their sketches of communal unity. It’s a detail that is instantly jarring, and it helps attune the viewer to the physical limitations of document-keeping that any attempt at pristine historicization must contend with, while also clueing us into the representative mode to follow — subjective expression opposed to anecdotal specifics or authorial dictates, its meaning decided upon by the beholder. Ailey’s blow-by-blow exposition on his influences, instincts, and the events of his work’s occasioning (such as the passing of his friend, Joyce Trisler, and his mother’s birthday) plays second fiddle to their final enactment, vivifying the crises and concerns of his day. Rejecting a full-bodied elucidation of the creative process and its material, emotional and psychological demands that a more conventional portrait might’ve achieved, Wignot looks instead to the finished product on-stage. In doing so, she wisely forgoes prescriptivist address and rises to meet the demands of Ailey’s abiding vision: art’s capacity, as a universal language, to resonate across arbitrary social markers and academic taxonomy.

All this shouldn’t take the shine off Annukka Lilja and Rebecca Kent’s (editor and archival producer, respectively) impressive work in post-production. Their eye for memorable sequences in the available footage of Ailey’s productions and their proficiency at layering them together lends heft to the otherwise anodyne commentary. Naiti Gámez likewise delivers, situated closer to the present as she lenses the goings-on of the Alvin Ailey American Dance Theater and its preparations for a new piece, “Lazarus” (which premiered back in 2018). Her camera keeps dancer and director alike on an even keel, each continually effaced as a minor component in a major constitution whose coherence depends on their most intimate decisions and calculations. Described as Ailey’s final “breath out,” it’s hard not to see the company, unmatched in its trade, as proof of the undying passions and traditions that survive us.

Writer: Nicholas Yap

Together Together

It’s never a promising sign when a film’s opening credits mimic a certain Woody Allen style, white Windsor font on a black background, a half-familiar jazz tune opening things up. But writer/director Nikole Beckwith’s gentle new comedy Together Together excels in subverting expectations, a modern-day love story that celebrates platonic friendship above all else. There are myriad ways this material could have gone wrong, seemingly custom-built to be the most basic romantic comedy: Matt (Ed Helms), a single man in his mid-40s, forms a close bond with Anna (Patti Harrison), a 26-year-old woman hired to be the gestational surrogate for his baby. From its opening moments, the film makes clear that neither is on the lookout for a romantic relationship, and certainly not with each other. Indeed, the script is indeed so persistent in this regard, especially in the early going that, for a while, it feels like a lazy misdirect, with Matt’s well-meaning but controlling behavior toward Anna reaching sitcom levels of broadness.

It’s only later, once the film fully settles into its own pleasant, low-key groove, that it becomes clear that those early shenanigans actually serve a purpose: to establish and elucidate the particular human connection these two eventually find in one another. These are not tragic souls harboring dark secrets, and in one particularly strong scene that speaks to the kind of intimacy at play here, the two open up about their past struggles, spurred by the question, “Why are you alone?” The answers they provide are remarkable in their mundanity, but they also speak why they would be drawn to one another at this specific moment in their lives, a turning point for both. Beckwith even has a nice callback to those opening credits, detailing how Woody Allen is a disgusting letch who openly pursued women half his age, a bit of finality for any viewers still holding hope for any possible sexual or romantic attraction between Matt and Anna. Moments like this reveal a cleverness that does little to draw attention to itself, as welcome a development as it is rare. All of this restraint is helped immensely by two leads whose acting styles so effortlessly complement one another and the material: Helms plays into the sweet-but-slightly-obnoxious persona he cultivated as Andy on The Office, and comedienne Harrison, in her first starring role, brings a much-needed tartness to the potentially saccharine proceedings. Their chemistry is so strong that even the film’s pitch-perfect ending can’t help but feel like a letdown, as these are two characters so worth spending time with. If Beckwith wants to pull a Before Sunset and catch up with these characters in nine years, it’s fair to say that I’d be at the front of the line for Apart Apart.

Writer: Steven Warner

Marvelous and the Black Hole

Like a forgotten remnant of a mid-2000s edition of Sundance, Marvelous and the Black Hole would’ve fit right in with the numerous post-Napoleon Dynamite, post-Little Miss Sunshine quirk-fests that littered movie theater screens. Proof that what Wes Anderson and Michel Gondry do is harder than it looks, Marvelous takes all the clichés of the coming-of-age, mismatched buddy movie, and scribbles a bunch of weird nonsense in the margins. Here, attempts at portraying real human behavior butt up against sitcom-style shenanigans, with everything pitched to the rafters. Friendships get formed via montage, life lessons are learned, and deeply-rooted family conflicts are mended in a tidy 80-minute runtime, all accompanied by a treacly score. It even ends with a stage performance. Fancy that.

Sammy (Miya Cech) is a typical disaffected teenager. Still reeling from the untimely death of her mother, she’s lashing out at her father (Leonardo Lam) for having a new girlfriend and keeps getting into trouble at school. Dad gives her an ultimatum: take a class at the local community college to try and get some direction, or it’s off to a boot camp for juvenile delinquents. Sammy reluctantly agrees, attending a business class and eventually meeting kooky magician Margot (Rhea Perlman). Under the aegis of teaching Sammy about her “small business” — Margot makes a living performing for children — the two gradually form a friendship while Sammy discovers a passion for sleight of hand. It’s all pretty straightforward, going exactly where you think it will and hitting every beat along the way. Writer/director Kate Tsang tries to inject a little life into this moribund scenario, but these stylistic flourishes are themselves mostly just collections of other, different clichés. Random animation periodically appears on screen, while Sammy has daydreams that manifest as faux-black & white, silent movie footage.

Tsang got her start writing for Adventure Time and Steven Universe, and Marvelous works best when it leans into bite-sized snippets of comedy. But it’s hard to build a feature out of bits, and the laughs are few and far between. Characters are defined by useless quirks, like Sammy’s sister’s addiction to a goofy video game or Margot’s habit of stealing toilet paper wherever she goes. More troubling and pointed is Sammy’s habit of tattooing small black X’s on her thigh when she gets particularly angry, an obvious analog for self-harm, but one here softened so as to be less shocking for potential younger viewers. It’s the kind of specific detail that grounds Sammy’s character in an actual, recognizable reality and suggests a more dangerous pathology at play, but, of course, this is dropped as soon as Sammy makes her new friend, and never brought up again. That’s really the film in a nutshell, creeping up against something that feels authentic and then quickly retreating back into idle tweeness. The cast is game, and Tsang can compose a frame, but there’s just not much here that genuinely compels.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Comments are closed.