Here Are the Young Men fixates on its most histrionic narrative beats and hypermasculine conflicts at the expense of its greater strengths.

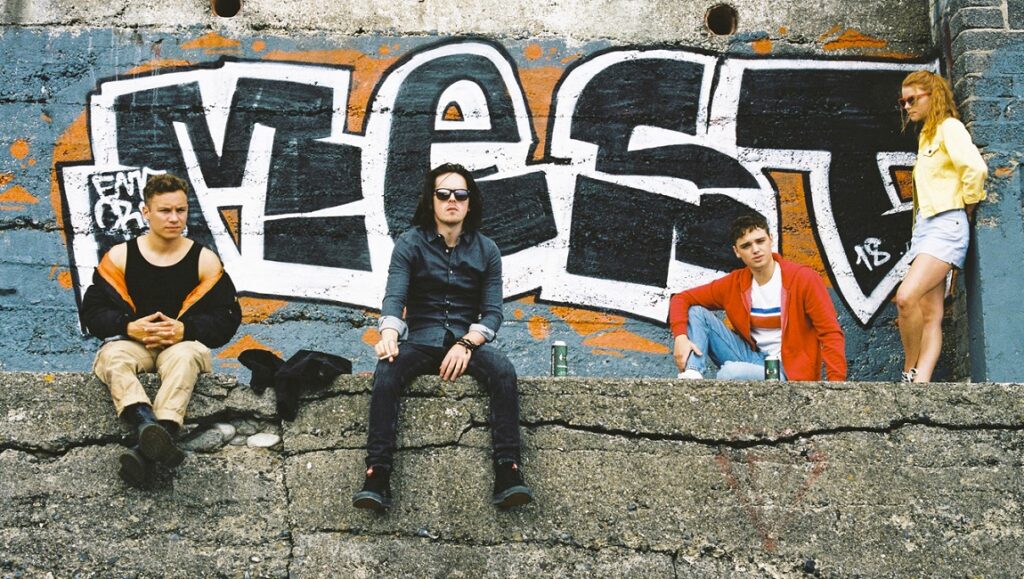

Set in 2003 Ireland, Eoin Macken’s Here Are The Young Men follows Michael (Dean-Charles Chapman), Kearney (Finn Cole), and Rez (Ferdia Walsh-Peelo) over the summer after they’ve left high school. Early on, the three witness the accidental death of a child, and their individual reactions take them on diverging paths. Michael pursues a relationship with best-friend Jen (Anya Taylor-Joy), Rez sinks into a deep, drug-fuelled depression, and Kearney, exhilarated by the experience, becomes increasingly cruel and sociopathic, spurred on by a fantastical vision of America.

With its nightclub-colored lighting and kinetic soundtrack, Here Are The Young Men embodies a spirit of young, easy-going confidence that helps distract from its weaknesses and gives the superficial impression of a better film. Director Macken’s filmmaking approach here is decidedly of the “throw everything at a wall to see what sticks” variety, and this lack of restraint is both the film’s greatest strength and its greatest weakness. The bold, monochromatic aesthetics of Macken’s club and party scenes, for example, perfectly complement the heightened realities of adolescence and of drug use, but the film’s forays into a dreamlike television studio feel largely clumsy and amateurish by comparison.

While in 2003, Here Are The Young Men and its distinct bluntness might have slotted in well next to contemporaries, in 2021, the film’s unironically “edgy” plot feels considerably dated. Elsewhere, while the film’s title gives no indication that it’s likely to pass the Bechdel test, but Here Are The Young Men is so callous in the way it shoves women aside that its casual misogyny begins to feel egregious. The film’s female characters exist only as vessels to absorb and reflect the cruelty and insecurity of men, and Macken’s refusal to engage with his own constant sidelining of women feels woefully ignorant in 2021. Beyond being borderline offensive in its inequity, Macken also simply wastes his cast with this single-minded focus. Anya Taylor-Joy, despite being the charismatic heart of the film, is relegated first to “girlfriend,” and then further demoted to “plot-device” — it’s to Taylor-Joy’s credit that she still manages to craft an engaging performance despite the stacked deck of female ambivalence on display here. Similarly, Ferdia Walsh-Peelo’s character Rez, the most openly vulnerable of the boys, gets quickly shunted aside to make room for Michael and Kearney’s more attention-grabbing, hypermasculine conflict. While Chapman and Cole’s performances are technically on par with their co-stars, the film isn’t concerned with anything outside the pair’s conflict, up to and including the boys’ friendship. What’s ultimately wrought of this male-centric and narrow focus is a colossal void at the center of the film, one that is only partially filled by Anya Taylor-Joy’s unstoppable charisma.

Comments are closed.