Once seen as a tragic fall from grace, today it shouldn’t come as much of a surprise to hear someone sing the praises of the movies Francis Ford Coppola made in the 1980s. Starting with One From The Heart in ’81, the maverick director followed up Apocalypse Now with a string of ambitious, deeply personal films, nearly all of which were commercial and critical flops. (The few bright points that he did manage, like for-hire job Peggy Sue Got Married, were still only modest successes at best — nothing approaching the heights of his ’70s work.) Cruelly underappreciated at the time, history has been kind to Coppola and his mad vision; many of these works that were initially written off as impenetrable and self-indulgent have gained admiring audiences with time, and what was before considered a dark decade for the director now seems to clearly constitute his richest and most fruitful period, at least in this critic’s eyes.

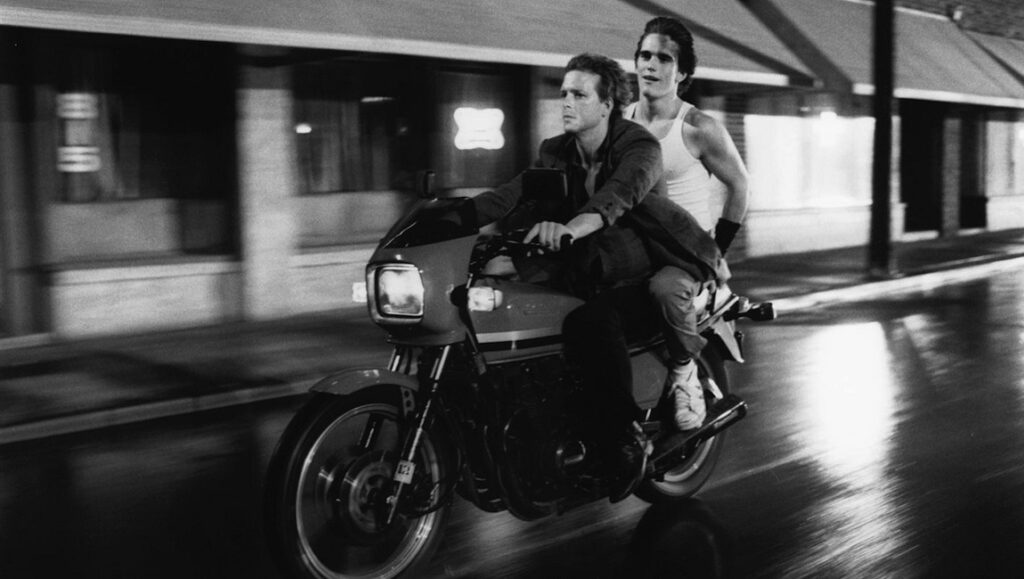

Rumble Fish (1983) is as exemplary a work of this period as any, a masterpiece wildly out of step with anything else Hollywood churned out at the time (or since). A comparison with Coppola’s other film released the same year, The Outsiders, is inevitable and illuminating: both are adaptations of teenage melodramas written by S.E. Hinton, and they were shot back to back in Tulsa, using the same crew and carrying over some notable cast members (namely Matt Dillon and Diane Lane). With The Outsiders, Coppola was upfront about his intentions to produce a “classically-made film,” wherein he “obeyed all the rules” (a concession prompted, undoubtedly, by the disastrous reception of One From The Heart). Rumble Fish, on the other hand, came to represent a reward for his obedience, “an opportunity to make something a little wilder, a little more experimental.” And indeed, though it would be natural to assume some commonality due to the source material and production, the difference in approach couldn’t be more stark. The Outsiders is a fine film, and one that sometimes gets short shrift amongst Coppola fanatics, but Rumble Fish is something else entirely. The warm nostalgia of the former is dispensed in favor of severe black and white photography, oblique camera angles and compositions drenched in shadows demonstrating a clear indebtedness to German Expressionism and film noir. Plot takes a backseat here to the point of abstraction, with Coppola letting his images bear the film’s considerable emotional weight. It’s easy to see how this baffled moviegoers at the time, but the film offers so much if one is willing to adjust to its unique language.

“Time is a funny thing,” mutters Benny, the aloof bartender played by Tom Waits, in an unusual aside about a third of the way into the film. But by the time of his brief soliloquy, such a statement is almost redundant. The film’s slippery temporality is signaled in its very first moments, a time-lapsed sequence of clouds rushing across the sky, glinting off of the sharp urban geometry of Tulsa’s downtown skyline (these images function as a motif, recurring periodically). The montage is accompanied by Stewart Copeland’s avant-garde score, a mix of drums and metallic sound collage replete with all sorts of percussive ticking, meant to serve as an aural complement to the clocks that haunt so much of the mise-en-scène. We’re introduced to Rusty James (Matt Dillon), a 17-year-old delinquent and the leader of a ragtag crew of high school miscreants, as he receives word that he’s been challenged to a brawl by a rival leader. Rusty James (he’s almost always referred to as such, never just “Rusty” or “James”) seems to relish this opportunity for bloodshed, but it soon becomes clear that his romantic vision of street gang violence is warped by a peculiar nostalgia. He pines for the glory of the not-so-distant past — “a gang really meant something back then” — a past that he himself didn’t live; he was only able to glimpse it as an observer to his older brother, the now-legendary Motorcycle Boy (Mickey Rourke). When the film begins, it’s been two months since the Motorcycle Boy (no further name is given) suddenly took off for California, but his looming presence is felt constantly, even in physical absence. We learn that this fight would go against a truce called by the Motorcycle Boy before he left, but Rusty James hardly cares, so intent on living up to his brother’s reputation is he.

The rumble is one of the film’s most striking sequences, a stylishly choreographed battle taking place in a derelict warehouse, the manic energy of the combatants matched by the strobing lights and industrial hum of their concrete environment. Yet, the most memorable moment is the hush that falls over the gathered crowd upon the Motorcycle Boy’s unexpected arrival. Even the trains that we see perpetually rushing past the windows seem to take pause. Later, we hear someone refer to him as a “prince…like royalty in exile,” a fitting way to describe the imposing aura that he casts. And with the elder’s entrance, we can immediately begin to sketch out a dichotomy between the two brothers. Even just a look at their respective faces is revealing: Mickey Rourke’s craggy, acne-scarred skin and twinkling eyes indicate a mysterious wisdom and a world-weariness far beyond his age (Rourke was nearly a decade older than his 21-year-old character), while Matt Dillon’s sharp cheekbones and slack-jawed stare suggest the opposite. Their dynamic is best summed up by Rusty James’ loyal friend Steve (Vincent Spano), who remarks: “the Motorcycle Boy? I never know what he’s thinking. But you? I always know what you’re thinking.” The Motorcycle Boy is soft-spoken and intellectual — “a deep motherfucker” — while Rusty James is brash, wearing his fiery emotions nakedly on his sleeve (and as far as articulating those emotions, he can rarely muster more than an impassioned “Fuck, man”). Rusty James’ sometimes-girlfriend Patty (Diane Lane) puts it sweetly: “you’re smart, you’re just not word smart.” Despite this, Rusty James repeatedly insists that he’s going to be and look just like the Motorcycle Boy when he’s older, a patently delusional claim that speaks to the skewed lens through which he sees the world. The extent of that delusion becomes more and more clear as the film progresses. Eventually, the Motorcycle Boy confirms what we had already surmised, that this glorious past that Rusty James is so fixated on “wasn’t anything (he) think(s) it was.” In a certain sense, the Motorcycle Boy is like the philosopher in Plato’s Allegory of the cave, returning to free the street kids from their prison, but struggling to wrench them away from the illusory shadows on the wall. Rusty James is stuck grasping for a past that never really existed, unable to see the depth in his beloved brother’s personhood, and inevitably failing to match up to the image that he has constructed.

Coppola’s decision to shoot in black and white is most easily read as an expression of the Motorcycle Boy’s color blindness — or perhaps, given that the bulk of the film is tied to Rusty James’ perspective, we can complicate things further and read it as a reflection of the younger brother’s distorted view, the blindness that comes as a result of chasing after his brother’s footsteps. Such a reading lends even more weight to the film’s few splashes of color, namely the titular rumble fish, which appear in the window of a pet shop in full color, even as the rest of their environment remains black and white (savvy use of rear projection is responsible for this feat). The violent fish need to be separated from one another to keep them from fighting, so vicious are they that when holding a mirror up to their tank, they will go after their own reflection. However, the Motorcycle Boy becomes convinced that the fish would be peaceful if only they were set free into the river: “I don’t think they’d fight if they had room to live.” The fish are of course a metaphor for the brawling street gangs, but the Motorcycle Boy sets out to make that metaphor literal, willfully becoming a martyr to free the fish, and thereby also freeing his brother. The fish, and their beautiful colors, represent a way out of this decaying urban wasteland, an alternative to the black and white vision that Rusty James has locked himself into.

There is a peculiar moment, coming just after the Motorcycle Boy is shot dead and the fish released. Rusty James is restrained by a few cops and pressed up against their car; catching his own reflection in the car’s window, he becomes enraged, attacking his mirror image, and as he does so, the image shifts from black and white to full color — the only such shot in the entire film. It’s a moving way of linking Rusty James and the embattled fish, and much like his colorful counterparts, he is able to find peace once freed from his constraints. It might be said that Coppola is operating formally in much the same way Rusty James is operating existentially: looking to the past as a means of forging a way forward. The past for him being not just the setting of the ’60s, but also the work of cinematic forebears like F.W. Murnau or Orson Welles. But Coppola understands something that Rusty James struggles to, that merely emulating the past is a dead end. And ultimately, the film succeeds not because it’s a spitting image of Murnau or Welles or any other film (it’s not), but because Coppola is able to synthesize those older works with his own sensibilities, bringing the past into the present, and pushing boldly ahead into the future. Rumble Fish is a film effectively unmoored from time, free, much like that final image of Rusty James gazing out on glimmering waves of the Pacific Ocean.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.