Scarecrow

Something incredible is brewing in the Sakha Republic (Yakutia). Over the last twenty years, this large yet sparsely-populated territory situated in the far-flung and frosty reaches of Eastern Russia has been slowly but surely building a robust regional cinema separate from the Russian film industry writ large. Sakha films — which range from melodrama to horror to recognizable arthouse, and usually feature the indigenous Sakha language (Yakut) rather than Russian — sometimes even outperform Hollywood blockbusters in Yakutsk, the region’s urban center. Over the last decade, these small-budget films shot by self-taught directors aiming to capture the life and traditions in the land of permafrost, have started to make their presence felt not just locally, but at Russian film festivals and on the international stage as well. Dmitrii Davydov’s Scarecrow is a fantastic encapsulation of the type of talent that this thriving film scene is nourishing, and suggests that the possibilities of this burgeoning film center, affectionately and colloquially known as “Sakhawood,” are as vast as the Siberian landscape that surrounds it.

Despite its ominous poster and unnerving nature, Scarecrow shouldn’t be categorized as a horror film; its central parable of a healer shunned and scapegoated by her village neighbors fits more neatly within the bounds of magical realism. Better yet, its convergence of haunting inner turmoil and themes of faith and sacrifice calls to mind the aching cinema of Carl Th. Dreyer, with his withering depiction of witch trials in Day of Wrath springing first to mind. And in casting folk singer Valentina Romanova-Chyskyyray as said healer, Davydov has found a lead whose stark performance here rises to the shattering intensity of Dreyer’s unforgettable heroines. In an unsettling prelude of what’s to come, the opening shot shows her standing still in a blinding field of snow, arms out and rigid like a scarecrow (a nickname the villagers taunt her with), her breaths harried and sharp, repeating in a chilling mechanical rhythm.

The next scene shifts into night, and following a police patrol matter-of-factly escorting the healer to their station, we learn her presence is intended as a last-chance attempt at saving a dying gunshot victim. Davydov shoots in a shaky handheld that bobs and weaves with the action, while the soundtrack details the cadence of boots crunching and squeaking their way through the snow, peppered with the officer’s heavy breaths, and transitioning viewers into the bracing realism that marks the film. It’s here, at the station, that we get the clearest glimpse at the mystical act of healing which will be hidden from us in the later sections. She undresses and climbs on top of the victim, her face pressed to the bleeding open wound. The desaturated color palette looks jaundiced, and meaningfully marries the surrounding squalor to an act that approaches the divine.

Scarecrow follows a pattern moving forward, as villagers who are vicious to her in public, out of either superstitious fear or skepticism, proceed to make visits in private for treatment of their maladies. After each session, her body rebels, she vomits bile and covers up her pain with drink, a bottle of vodka perpetually in her clutch. Romanova-Chyskyyray is arresting in her commitment to the performance; not only does she push her body into contortions, all flailing limbs and fugue state groans, but she hammers at a piercing sadness as well. In one of the strongest scenes in the film, she sits in a boiler room with a man who seems to be her confidant and likely lover. After he shovels coal into a roaring furnace and returns to sit by her side on his small bed, she collapses into weeping, and the two exchange words we cannot hear, her face lost in anguish, his in somber sympathy. (Is this perhaps a tip to Dreyer, whose best-known shot is Falconetti’s silent tears in The Passion of Joan Of Arc?)

As we gradually learn more about her past, her pain intensifies, and as the film moves toward its final gesture (captured like so much that precedes it in a neatly-crafted composition), a larger theme reveals itself. Davydov draws on the shamanistic traditions of the indigenous Sakha people to inform the substance of his parable, but the throughline of the “scapegoat” touches on the rawness of current events. Like so much of the world, right-wing nationalism and anti-immigrant violence have bubbled over in Yakutsk as well. In 2019, a violent nationalist mob launched an attack on a street market run by Kyrgyz migrants, demanding the expulsion of Kyrgyz and other Central Asian peoples. Within this context, Scarecrow forms an emphatic portrait of a timeless story, a person denied by their community despite their gifts and sacrifices, and the desperate conditions that foster this rejection. Watching the culminating miracle of the film, one can’t help but think about the real-life miracle of its journey to Rotterdam. Davydov, a primary school teacher with little formal training, has now directed his third feature film, a work of such resonant power, nuance, and craft that it’s made its way into one of the most esteemed international festivals. It’s easy to watch lumbering Hollywood monopolies form into ouroboros content mills and consider cinema dead; it’s much harder to do so with your eye on the Sakha Republic and a myriad of comparable film movements thriving worldwide.

Writer: Igor Fishman

The Amusement Park

Long recognized as one of the absolute masters of horror, the subsumption of George A. Romero’s zombie iconography into the popular lexicon has, perhaps inevitably, gradually sanded off the barbed political edges of his best work — a common enough side effect for anything that becomes part of the monoculture. The new restoration of Romero’s long-lost 1973 film The Amusement Park is, then, in addition to being a remarkable movie, also a startling reminder that while Romero was indeed a humanist, he was also a fierce critic of the institutional failures of American society.

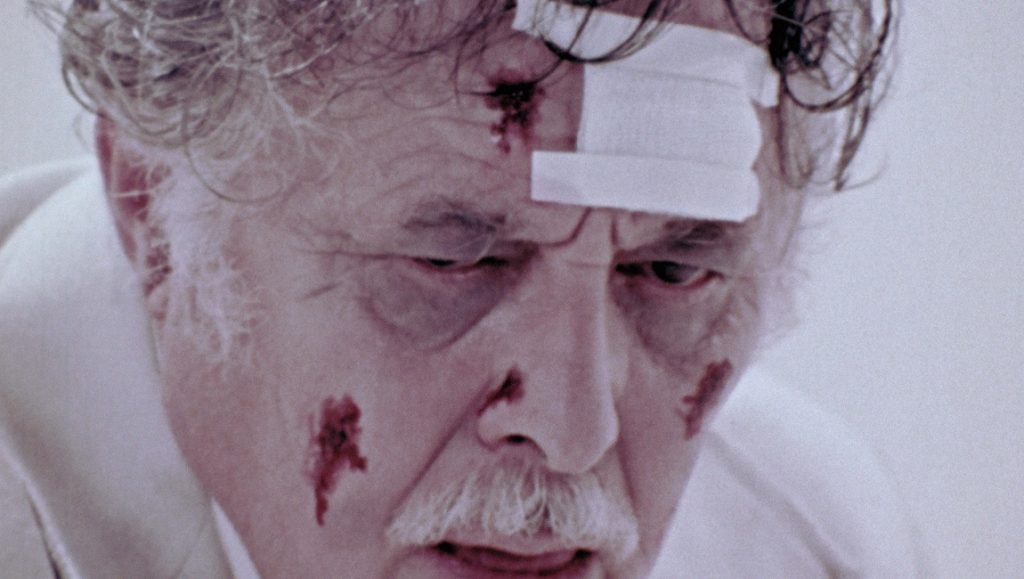

Originally commissioned by the Lutheran Society in 1973 to raise awareness of the plight of the elderly in America, The Amusement Park was never officially released. Presumed lost for decades, a 16mm print was discovered in 2018 by Guillermo del Toro and author Daniel Kraus, restored by IndieCollect and the Romero Foundation, and is now being released by Shudder with the blessing of Romero’s widow, Suzanne Desrocher-Romero. Its original mission statement — designed on purpose to serve a blunt, pedagogical function — gives The Amusement Park a rare clarity of purpose. It begins with actor Lincoln Maazel addressing the audience directly, briefly describing the impetus of the project while listing the numerous ways that the elderly are ignored or otherwise victimized in day-to-day life. Ending his monologue with a heartfelt plea for sympathy, Maazel then enters a white room where he sees a haunted specter of himself sitting down, bloodied and bandaged, barely able to speak. Maazel bids good day to this doppelgänger and proceeds to enter the park, which has been designed as an allegorical synecdoche for contemporary America.

Romero wastes no time savaging what he views as a capitalist shell game; to gain entrance, elderly people are shown lined up to sell their belongings in exchange for tickets to the various attractions. From there, Maazel encounters all manner of indignities: signage declaring various entertainments too extreme for older patrons, indifferent or actively hostile younger people, an infirmary that looks like a war zone. There are odd, almost avant-garde touches to the environment; a bumper car ride leads to an actual accident, where police disregard an old woman’s account of the incident in favor of a condescending younger man’s obvious lies. At one point, Lincoln says hello to a gaggle of children, only to be waved away by concerned parents who assume he’s a dirty old man. Later, he befriends another child just to be summarily dismissed by the girl’s disinterested mother. In the film’s most overtly horrific scene, a young couple visits a fortune teller for a glimpse into their future. She proceeds to show them a nightmarish vision of old age, the pair living in a rundown tenement, unable to reach a doctor on the phone as the man succumbs to something like dementia. Romero is constantly critical of capitalism, from overpriced health care to unscrupulous bankers to predatory lenders (pickpockets even have the run of the park).

Anecdotally, the film was never released as the producers deemed it too harsh for their original purposes, but one can easily imagine the moneymen being horrified at the precision of Romero’s merciless critique. Produced the same year as Romero’s The Crazies and Season of the Witch, The Amusement Park manages to evoke the jagged movements and frenzied pacing of the former with the elliptical, associative editing of the latter (Romero almost always acted as his own editor, one of his underrated talents). By the time this 53-minute film is over, the audience is as exhausted and wrung out as Maazel, who returns to the white room fully transformed into the bloodied version of himself. A door opens, and another Maazel enters, replaying the first scene from the film in a kind of time-looped Möbius strip. And so, Romero ends the film not with feel-good platitudes or a grand awakening, but with the despairing notion that this vicious cycle is doomed to repeat itself.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Fat Chance

Laird Cregar, a man with virtually no name recognition today, was, in his time, a popular American stage actor, one who was fast-tracked to Hollywood and appeared in a few box-office hits in the early ’40s, and who tragically died at age 31 right before hitting it big. While his official cause of death was a heart attack — one brought upon by an extreme diet of heavy amphetamines and gastric bypass surgery — close friend George Sanders characterized it more sensationally: “Hollywood virtually assassinated Laird Cregar.” He was a short, closeted, heavy-set man who was obsessed with his own body image, to the point that he was willing to die for it. Studios saw him as a natural rival to Vincent Price, and pitched him as such; Cregar, instead, wanted to be a romantic lead, and was fearful of typecasting based on his portly appearance. So, he lost over 100 pounds in less than a year, a process that put so much strain on his body that it ultimately killed him. While upsetting on a personal level, Cregar’s death is illustrative of a certain type of Hollywood preoccupation with one’s image and the lengths people go to preserve their faltering egos: that being beautiful comes before anything else. Even in death, Cregar’s image still remains his most noteworthy attribute.

While Stephen Broomer’s latest feature-length archival deconstruction (in a rather literal sense of the word) is tangentially concerned with this type of conceptual mythos, it would be more accurate to describe Fat Chance as interested with image-making less as a human practice and more as a materialist processes — one that can be doctored and mutilated in unforeseen ways, much like Cregar and his fluctuating body weight. By chemically altering, overexposing, crumpling, and at times overlaying 16mm footage from the final two cinematic works that Cregar appeared in — The Lodger and Hangover Square, both helmed by John Brahm — along with a few others, Broomer crafts a degenerating potpourri which operates in tandem with his subject’s own personal degradation. Because of these various physical manipulations, it becomes difficult to parse where one collected image begins and the other ends, turning these high-fidelity reproductions into massive, amorphous figures of abstract projected light, seemingly ready to burst and catch fire if not for their crisp transfer to digital.

This post-production process recalls Phil Solomon’s Twilight Psalms in terms of aesthetic design, but Broomer’s intrinsically haptic rhythms and moody ambiance are indebted to his fellow Canadian avant-gardists R. Bruce Elder and Guy Maddin (both of whom are thanked in the end credits), influences that become especially clear during a few segments that bombard viewers with an overwhelming amount of visual and sonic stimuli. This also means that Fat Chance is far more interested in expressing the full brunt of its formal abilities than in acting as psychoanalytic subtext for Cregar, beyond having him look forlorn on a few occasions, which, given the natural limitations of an exercise such as this, is probably for the best. That said, the emotional gravitas that’s signaled toward the finish — concluding with the blazing end to both Hangover Square and this work as a whole — doesn’t particularly feel earned, and the soundtrack is often foregrounding this affective attempt in some rather obvious ways that feel as blunt-force as some of the rapid editing. But as a filmic experience, its visual ideas never threaten to become monotonous, and that in and of itself is something of a feat considering how anguished the enterprise tries to be. In fact, in somewhat morbid and possibly contradictory fashion, Broomer elucidates the pure ecstasy that destruction can provide.

Writer: Paul Attard

Capitu and the Chapter

A favorite on the international festival circuit with a robust filmography of at least 40 films made over 50 or so years, Júlio Bressane looms large as one of Brazil’s most enduring experimental filmmakers, specializing in postmodern syntheses of the literary, theatrical, and cinematic that indulge in silly humor and soapy dramatics. Though, of course, an artist this prolific and inventive transcends simple summaries of aesthetic and predilection, further complicated by very limited distribution outside of Brazil, with seemingly none of his movies ever finding distribution in the U.S.

This could either be a hindrance or point of interest for Western audience members (French and Italian distributors are a little more favorable to his work) approaching Bressane’s newest film, Capitu and the Chapter (or, Capitu e o capítulo), a late work fixated on the films of this director’s past as much as it is the nominal plot. Adapted from Machado de Assis’ 1899 novel Dom Casmurro, Capitu and the Chapter deconstructs its source narrative and rearranges it as a series of tableaux with characters speaking at each other in monologue, blocked and staged in stilted, Brechtian fashion. A fairly standard tale of infidelity and its related envies and insecurities, Capitu and the Chapter filters its narrative through a framing device, the source novel’s title character, Dom Casmurro, holed away in an empty library, imprisoned in a frame of dusty books and shelving, committing his memories to paper in the hopes of making sense of his romantic misfortunes. Though, as previously implied, the plot that unfolds in these writings isn’t the film’s most interesting element, essentially detailing the paranoias of a young man beguiled and intimidated by his charismatic, provocative wife (the Capitu of the film’s title). This is the tired, sexist material of any number of modernist novels and cinema, but it provides a convenient shape for the film, as well as a (suitable enough) context for Bressane to experiment with aesthetic approximations of memory. For some, the former will negate the latter, particularly if they aren’t invested in Bressane’s work to begin with, but Capitu and the Chapter isn’t all as dour as the plot would suggest, with many of the scenes tonally pitched towards camp and soap. Sequences of bourgeois parties represented by four people dancing furiously in silence alleviate the weight of the film’s austerity, as do the eventual depictions of violence, staged to render the perpetrator pathetic.

Capitu and the Chapter isn’t necessarily a perfect rendering of the implied thesis, but it is obviously the work of an ingenious visual storyteller, able to convey emotions that aren’t being expressed in dialogue or performance using the tools of cinema many no longer care to toy with —blocking and sound design, most overtly. This also comes with a refreshing lack of pretension, the filmmaker not afraid to go for broad comedy or slapstick, and readily weaving himself into his own narrative in a way that is self-deprecating but not flagellating (scenes from his previous films are occasionally edited in proximity to scenes of Casmurro writing the story, and the credits feature extensive behind-the-scenes footage of him directing). Infidelity and memory are fairly well-trod concepts in the world of cinema, especially within the sort of arthouse milieu Bressane is associated with, but Capitu and the Chapter gets by with humor and candor, recognizing the act of remembering to be a mortifying one.

Writer: M.G. Mailloux

Fan Girl

Celebrity culture is a cursed behemoth of cringe-inducing endorsement. With each successive year, time’s cyclicism is once again proven amid an abundance of needless drama and controversy. Apology videos tacitly condoning toxic behavior are now essentially a joke; in an environment so crazed for attention and clout, emotional abuse too often comes as part of the package of human connection. That’s the rough thesis of Antoinette Jadaone’s latest feature, Fan Girl, a tense Filipino coming-of-age drama that frequently attempts to dissect the toxic modes of celebrity entitlement. Captured in claustrophobic 4:3 aspect ratio, Jadaone consistently fixes her focus on protagonist Jane (Charlie Dizon), which over the course of the film then traps the viewer in various positions of social awkwardness and misconstrued power dynamics.

The premise of Fan Girl is conceptually simple on paper, yet Jadaone frequently implements clever framing and blocking to add an additional layer of subtext to the film’s narrative crux. Fan Girl is littered with clever imagery that emphasizes its symbols of division and power — a prominent example being the initial inciting event that divides Jane from her idol, Paulo (actor Paulo Avelino, playing a version of himself), in a moving truck. Jane is situated in the back of the truck — surrounded by an abundance of movie posters and gifts — as Paulo drives from the front seat, unaware of her presence. Another such notable shot comes at the moment of Jane’s verbal interaction with Paulo, where she is first seen spying on her idol from below, Paulo’s body framed on the upper floor.

Likewise essential and beneficial to the film is that it never shifts from its central perspective. Fan Girl is Jane’s story, after all, told through her eyes and informed by her fantasies. Each reveal, then, layers Paulo’s duality, as the film’s critical angle is prominently shown through Jane’s celebrity-fixated imagination that refuses to accept reality. It isn’t until the film’s third act that this facade breaks to unveil an ugly (if obvious) truth — that emotional abuse is largely, systemically forgiven for those in positions of power. Idolization is inherently linked to the concept of normalization, and through Jane’s eyes and warped perception, the viewer witnesses two cases of severe abuse that seem to stem from two different people in two different social constructs. Perhaps, then, more time and clarity should have been dedicated to this tense third act, which deepens and complicates the film’s ideas, especially when considering the film’s crucial final moments. But thanks to its interrogations — and clever mode of presentation — Antoinette Jadaone’s Fan Girl proves to be an endlessly fascinating character study that never once settles for easy answers.

Writer: David Cuevas

Death on the Streets

Death on the Streets is a rather sensationalist title for what’s ultimately a low-key slab of miserablism served up by Danish director Johan Carlsen. A one-note affair that mistakes topicality for depth, the film bends over backwards to present a “naturalistic” portrait of Midwest American strife that feels as inauthentic as the likes of such misguided studio pap as Hillbilly Elegy. Never-ending shots of corn fields and Kroger parking lots filled with pick-up trucks situate us squarely in the heartland, where the sun-kissed skies and seemingly endless acres of fertile farmland hint at a modest prosperity that eludes struggling farmhand Kurt (Zack Mulligan), a taciturn man desperate to support his wife and two kids. Refusing to take what he deems as handouts from friends and families — at least 20 of this film’s 90 minutes are devoted to people offering money — Kurt abandons his family out of the blue and heads to Atlantic City, taking on odd jobs and living on the streets to save up a little money to send to his loved ones, with whom he foregoes any sort of contact.

Death on the Streets is obvious in a way that borders on insulting. Carlsen and co-writer Micah Magee seem to be under the delusion that the story sketched here is somehow revelatory, as if viewers are entirely clueless to the struggles facing middle-class America, that poverty and homelessness can take on many forms and indeed affect millions. Countless Malickian shots of the natural beauty of middle America serve as an ironic contrast to the hardships faced by its inhabitants, while Atlantic City is presented as a depressing, gray nightmare where passersby barely flinch as they step over the body of a sleeping homeless man. Kurt’s pride ultimately sends him on a journey to which there can be no positive outcome, the film going out of its way to punish and humiliate him in ways that feel wholly unearned. Casting Mulligan in the leading role is the smartest thing Carlsen did, as the young man’s real-life troubled past was highlighted in 2018’s brilliant documentary Minding the Gap. If anything, Kurt feels like a natural extension of the Zack we saw in that film, a kindhearted but temperamental fuck-up whose good intentions were stymied by a lack of healthy familial support and growing up on the lower-rungs of an economically-depressed city. As presented here, Kurt is a blank slate, and it’s this prior cinematic exposure to Mulligan that does some heavy lifting the script fails to and fills in the gaps in a way that might not have been intended but prove sorely necessary. It also doesn’t help matters that the film fails to acknowledge that Kurt is so obviously struggling from severe clinical depression, and to even imply that this psycho-emotional circumstance is solely the result of his monetary struggles is both reductive and downright irresponsible.

Carlsen works overtime to infuse his film with a sense of naturalism, going so far as to hire a majority of non-professional actors, but rather than bolster his ethos, their lack of experience only proves distracting. The dialogue certainly isn’t doing them any favors, as it sounds like it was written by a galactic traveler whose only familiarity with Midwesterners is through bad television and movies. There are exchanges in this film that wouldn’t be out of place in the likes of The Room or Birdemic in terms of both writing quality and bonkers line delivery. The addition of a side character obsessed with nunchucks and ‘80s metal is especially perplexing, as it is tonally at odds with everything around it and comes across as rather mean-spirited, a case of “let’s all laugh at the weirdo” a la Napoleon Dynamite. And that’s beside impossible to parse moments, such as a scene where a woman tries to register Kurt to vote and he refuses by exclaiming, “I don’t give a shit what happens in this country.” Is the film blaming Kurt for his own predicament, or is it rather indicting an establishment that led to such feelings? If Death on the Streets has any sort of firm answer on its mind, it certainly isn’t sharing it with us, opting instead to end with a shot of a harvested field as it decays in cold winter months, punctuating its poverty porn approach with one final moment of self-serious metaphor-making on the way out.

Writer: Steven Warner

Comments are closed.