The Amusement Park is a remarkable work and profound reminder of Romero’s facility with pointed critique.

Long recognized as one of the absolute masters of horror, the subsumption of George A. Romero’s zombie iconography into the popular lexicon has, perhaps inevitably, gradually sanded off the barbed political edges of his best work — a common enough side effect for anything that becomes part of the monoculture. The new restoration of Romero’s long-lost 1973 film The Amusement Park is, then, in addition to being a remarkable movie, also a startling reminder that while Romero was indeed a humanist, he was also a fierce critic of the institutional failures of American society.

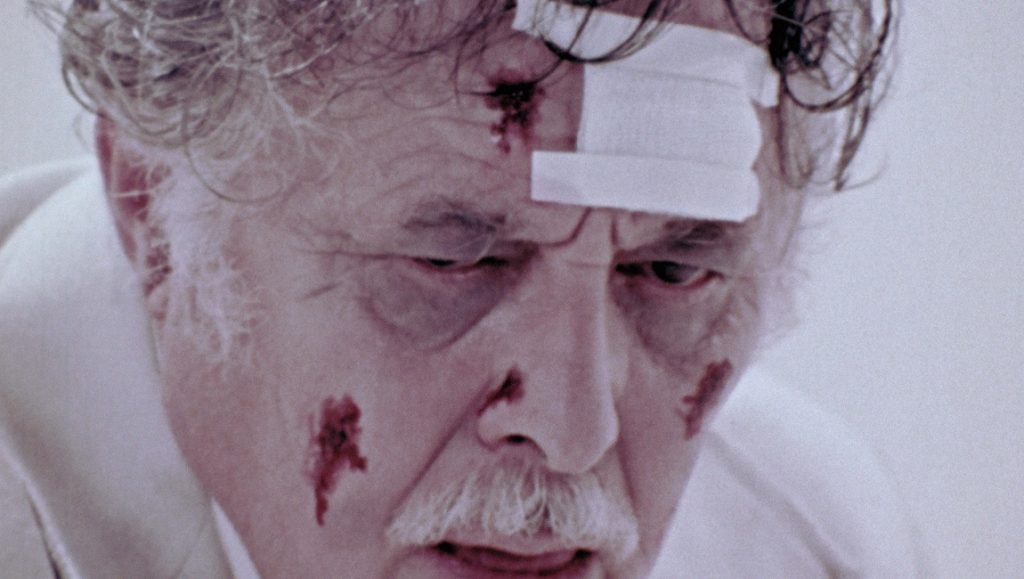

Originally commissioned by the Lutheran Society in 1973 to raise awareness of the plight of the elderly in America, The Amusement Park was never officially released. Presumed lost for decades, a 16mm print was discovered in 2018 by Guillermo del Toro and author Daniel Kraus, restored by IndieCollect and the Romero Foundation, and is now being released by Shudder with the blessing of Romero’s widow, Suzanne Desrocher-Romero. Its original mission statement — designed on purpose to serve a blunt, pedagogical function — gives The Amusement Park a rare clarity of purpose. It begins with actor Lincoln Maazel addressing the audience directly, briefly describing the impetus of the project while listing the numerous ways that the elderly are ignored or otherwise victimized in day-to-day life. Ending his monologue with a heartfelt plea for sympathy, Maazel then enters a white room where he sees a haunted specter of himself sitting down, bloodied and bandaged, barely able to speak. Maazel bids good day to this doppelgänger and proceeds to enter the park, which has been designed as an allegorical synecdoche for contemporary America.

Romero wastes no time savaging what he views as a capitalist shell game; to gain entrance, elderly people are shown lined up to sell their belongings in exchange for tickets to the various attractions. From there, Maazel encounters all manner of indignities: signage declaring various entertainments too extreme for older patrons, indifferent or actively hostile younger people, an infirmary that looks like a war zone. There are odd, almost avant-garde touches to the environment; a bumper car ride leads to an actual accident, where police disregard an old woman’s account of the incident in favor of a condescending younger man’s obvious lies. At one point, Lincoln says hello to a gaggle of children, only to be waved away by concerned parents who assume he’s a dirty old man. Later, he befriends another child just to be summarily dismissed by the girl’s disinterested mother. In the film’s most overtly horrific scene, a young couple visits a fortune teller for a glimpse into their future. She proceeds to show them a nightmarish vision of old age, the pair living in a rundown tenement, unable to reach a doctor on the phone as the man succumbs to something like dementia. Romero is constantly critical of capitalism, from overpriced health care to unscrupulous bankers to predatory lenders (pickpockets even have the run of the park).

Anecdotally, the film was never released as the producers deemed it too harsh for their original purposes, but one can easily imagine the moneymen being horrified at the precision of Romero’s merciless critique. Produced the same year as Romero’s The Crazies and Season of the Witch, The Amusement Park manages to evoke the jagged movements and frenzied pacing of the former with the elliptical, associative editing of the latter (Romero almost always acted as his own editor, one of his underrated talents). By the time this 53-minute film is over, the audience is as exhausted and wrung out as Maazel, who returns to the white room fully transformed into the bloodied version of himself. A door opens, and another Maazel enters, replaying the first scene from the film in a kind of time-looped Möbius strip. And so, Romero ends the film not with feel-good platitudes or a grand awakening, but with the despairing notion that this vicious cycle is doomed to repeat itself.

You can currently stream George A. Romeo’s The Amusement Park on Shudder.

Originally published as part of IFFR 2021 June Programme — Dispatch 2.

Comments are closed.