False Positive

Even though it’s sort of unfair to stack False Positive against Rosemary’s Baby, the movie is asking for it, and, unfortunately, the comparisons are not going to do it any favors. If you’re going to place a pregnant woman amongst a bunch of obvious gaslighters, and have her doubt her own sanity in the face of increasingly sinister circumstances, fearing for her life and that of her unborn child, it’s just something your film is going to have to tolerate. And while False Positive tries — not entirely unsuccessfully — to modernize some of its ideas and add some thoughtful seasoning, it’s also tremendously unexciting, rotely plotted, and, most egregiously, boasts a real letdown of a finale.

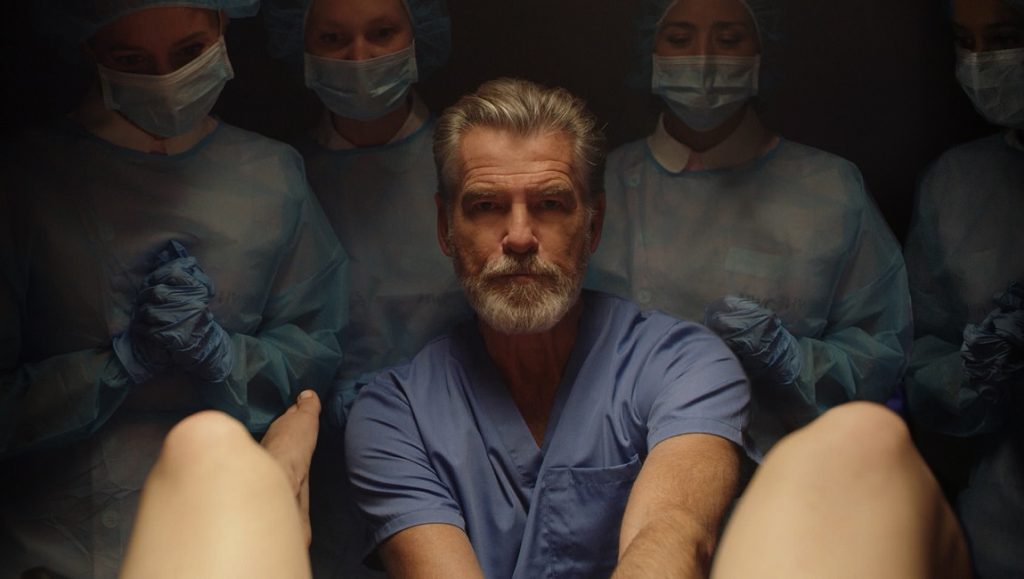

Lucy (Ilana Glazer, who also co-wrote) and her spouse Adrian (Justin Theroux, in the John Cassavetes role here) are wealthy and established New Yorkers. Her advertising career is blowing up, and he’s a successful surgeon. They’ve been trying to get pregnant for a couple of years without success, and so Adrian suggests — maybe even insists a little — that they visit Dr. Hindle (Pierce Brosnan, having some fun here), an extremely prominent fertility doctor who also happens to be Adrian’s former teacher.

Things are, of course, uneasy from the start. Hindle’s office is populated by Stepford-ish nurses (headed up by Gretchen Mol, very creepy), and Hindle himself is just the right sort of probably-mad scientist, with a cool but over-friendly and paternalistic demeanor. This guy’s just gotta be up to something. Meanwhile, Lucy is surrounded on all sides by a culture that seems to subtly weaponize her own eventual pregnancy against her. The other expecting women in her social circle — who all, tellingly, experienced varying degrees of difficulty conceiving — seem unsettlingly only identified with the state of being pregnant, talking about things like “Mommy Brain” and “Mommy Makeovers” in — again, of course — the most off-putting and ghoulish way possible. At work, a major account is handed over to a male co-worker (who makes sure to also note that she’s “glowing.”). And when medical complications finally arrive, well, you can imagine how that ratchets up the tension.

Which is to say that it’s all pretty predictable, if not in fine detail, then certainly in broad stroke. This is very perfunctory stuff, and any success hinges on sticking a landing that False Positive simply doesn’t do. It’s interesting to add male-dominated work and medical environments to the litany of people trying to tell Lucy they know what’s best for her, but that tree never really gets shaken too hard. The “Is it real or is it Mommy Brain?” question about Lucy’s sanity can obviously only go one of two ways, and it would be thematically pretty disingenuous to turn out to be all in Mommy’s head. So, materially not much happens as you wait around to find out exactly how — and in what way — evil Dr. Hindle is.

Glazer does a nice job of playing the buttoned-up, aspirational woman watching everything she wants unravel, but — and I know it’s unfair— seeing her here makes one ache for a dose of black humor beyond gently mocking materialistic rich white moms. There’s a really welcome little grace note involving Lucy’s (and our) perception of a Black midwife, but it’s not enough to really upend the (mostly) thuddingly obvious text here. And director John Lee doesn’t help himself by staging everything in long, placid takes with a color palette that tends toward gloomy gray (although one moment in particular, as Lucy stares into a black void in her apartment, is genuinely effective). And then there’s the reveal, which is a real loser, coming along with a bit of bloody violence, but nothing too tasteless. It’s really perfectly okay to try to craft a more ideologically modern take on a classic — you’re just not allowed to make it this dull.

Writer: Matt Lynch

Brighton 4th

There’s a scene midway through Levan Koguashvili’s Brighton 4th in which the film’s elderly protagonist, Khaki, explains to his sister-in-law that his health won’t allow him to work construction, only to immediately insist that she clamber onto his back so that he can prove his still-present strength. It’s a moment that feels authentic, a recognizable exhibition of the macho-masculine condition, and one that is illustrative of the film’s chief concerns: broadly, the notion of what makes a man — or, perhaps more accurately, what society says makes a man — and specifically, what makes this man, Khaki. The film’s narrative details support this theme: Brighton 4th opens with a scene of puffed-up posturing over sports, features multiple instances of emasculation as a result of gambling addictions, and builds dramatic tension from plot beats such as a man being in debt to his female landlord and a cadre of tough guy mobsters coming to collect. And then there’s Khaki, a former wrestling champion (played by Levan Tediashvili, himself a former Olympic wrestler) who takes responsibility for everyone in his orbit, the story following his trek from his native Georgia to the eponymous Brooklyn neighborhood to help his son get out from under money owed. He’s a stoic man, understated and by all accounts gentle, defined most by this selflessness, and the contrast that these attributes evince within this hyper-masculine milieu represents the film’s best quality. Director Koguashvili largely allows Brighton 4th to take its tonal cues from Khaki’s character, then, keeping proceedings languorous and de-escalating tensions that would otherwise reshape the film’s placid character; genre signifiers abound, but things remain low-key, never extending to the archness that can sometimes accompany mob-minded cinema.

But while the restraint is welcome, the film’s destination makes it another mostly nondescript “contemporary world cinema” effort. The film’s interrogation of masculinity doesn’t dig much beyond the surface, and it settles on a predictable, immensely sentimental ending. In a film industry dominated by men since its invention, the study of male fragility long ago ceased to be particularly interesting in and of itself, and Brighton 4th fails to either tether its interrogation to the underrepresented Georgian culture it depicts or meaningfully develop it beyond the cliches of sacrificial male tragedy. The film works better as character study: the context of Tediashvili’s true-life history lends emotional weight to the image of his weakening, 73-year-old body, particularly given the compassionate in-film circumstances of his endeavoring. DP Phedon Papamichael, for his part, does what he can to elevate the material, crafting striking images and, in concert with Koguashvili, helping to turn what might have otherwise been a laughable climax into an extended, wrenching image, shooting the aged subjects in widescreen and padding them with negative space, their bodies a huddled mass at the frame’s center. But while the unexpected tension between its subject matter and saccharine elements results in a film that often feels sweet despite its bleak terrain, it’s all rendered fairly colorless once Brighton 4th settles into its finale. For a film built from such particularities as the Georgian immigrant community and geriatric wrestling, things shouldn’t feel so underwhelmingly familiar.

Writer: Luke Gorham

Roadrunner

The late culinary connoisseur Anthony Bourdain once said “the greatest sin is mediocrity.” Regardless of the original context, this statement can be applied to a number of arenas: from the world of fine cuisine to the disastrous industry dedicated to inferior portrait documentaries to the arbitrary stylistic devices that pander to fandoms and the supposed livelihoods of famed celebrities. Incorporating all three, the rise of amateur nonfiction features that highlight a day in the life of such renowned artists and cultural icons can be most adequately regarded as celebrity-endorsed propaganda. In the case of a larger-than-life figure such as Bourdain, only a few filmmakers seem equipped to effectively tackle the difficult and turbulent life of the troubled television star. Thankfully, director Morgan Neville is on the shortlist and, in tandem with his talented team of committed editors, helps Roadrunner: A Film About Anthony Bourdain avoid the trappings of subpar portraiture, instead providing a unique study of the cycles of grief and acceptance told from the perspective of Bourdain’s colleagues following his death.

Prominently highlighting Bourdain’s career from the inception of his first publication, Kitchen Confidential, Neville’s extensive collection of B-rolls — including both hours of behind-the-scenes television footage and audio clips — provide an intimate glimpse of Bourdain’s ever-shifting personality. In one moment, a hard cut to silence seeks to emphasize Bourdain’s struggle with depression; in another, the interpolation of non-diegetic musical cues (ranging from the works of Brian Eno to Ryuichi Sakamoto) punctuates his loss of identity. Through simple editing tactics, Neville’s purposeful direction contextualizes his film’s thesis regarding media sensationalism and the search for normalcy amid a cesspool of cultural chaos. As Bourdain’s fame grows over the early 21st century, more clarity is afforded (both literally and figuratively), with the introduction of higher resolution camera footage and Bourdain’s personal struggles with past relationships. Even the shooting locations of the newly documented interviews are set in empty bars and abandoned dining rooms, mirroring the isolating effect of grief and symbolizing the pain that Bourdain’s death has caused amongst his social circle (and beyond) over the last few years.

There’s likely no easy salvation for the portrait doc, but Roadrunner makes a strong case that what the sub-genre needs is a concise purpose, a substantive reason to exist amid a sea of disposable celebrity worship. Neville’s understanding of his subject and broader subject matter, and his command of simple but effective mise-en-scene, provides a gratifying portal into Anthony Bourdain’s psyche and relatable struggles. The result of this meaningful probing and deep humanism is a film that offers enlightening and potent reflection, and affords closure not just to viewers and fans, but, with profound empathy, to Bourdain’s associates, friends, and lovers.

Writer: David Cuevas

The Neutral Ground

With Juneteenth a newly-minted federal holiday, it’s a fitting opportunity to revisit a particularly fascinating moment in our country’s ongoing reckoning with its white supremist past: the battle over four Confederate monuments in New Orleans, which comedian CJ Hunt tackles with humor and sensitivity in his documentary The Neutral Ground. Hunt, with his unassuming manner and deadpan delivery, has a Louis Theroux-like talent for inserting himself into uncomfortable situations and getting subjects to open up. He interviews all sorts of people for whom the term “redneck” is almost certainly a point of pride, including exactly the type of folks you’d imagine hanging out at a Confederate battle re-enactment. Through interviews and close reads of state secession papers, Hunt concludes that it’s impossible to remove slavery from the cause of the Confederacy — and therefore impossible for Confederate monuments to exist without upholding the philosophy of white supremacy. In fact, in one egregious example, the words “white supremacy” are literally carved into the stone — which you’d think would make the case for destroying all such monuments rather self-evident. And yet, 150 years after the Civil War, this group of insurrectionists still has a powerful grip on our nation’s imagination.

The reason is the Lost Cause, an ideology that derived from a need to make sense of the war’s unprecedented death toll and, above all, to separate the Civil War from the institution of slavery. Through the Lost Cause, the war was couched as an issue of “state’s rights,” a willful revision that persists today. Through this mythology — which, as one interviewer points out, was propped up by the North as much as it was created by the South — a false narrative of benevolent slaveholders and happy, well-treated slaves proliferated through school textbooks, pop culture, and other channels, including Confederate monuments. It’s no surprise, Hunt notes, that they were often erected in response to periods of Black enfranchisement, such as Reconstruction and the Civil Rights era. In 2015, the Lost Cause collided with the Black Lives Matter movement when, in response to the Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church shooting in Charleston, SC, the New Orleans City Council voted to remove four monuments throughout the city.

Hunt, who is Black and Filipino, was ambivalent about his Blackness as a child and young adult. It was only when he moved to New Orleans, with its large number of Confederate statues, that he began questioning what it meant for Blackness and the Confederacy to be forced to co-exist, over a century after the Civil War. Some of the documentary’s most fascinating and moving scenes depict Hunt’s introspection regarding his own Blackness, often through on-screen interviews with his father. This level of personal investment gives The Neutral Ground a sense of urgency and narrative growth that distinguishes it from other documentaries about the history of Blackness in America, such as Ava Duverney’s 13th.

The first half of The Neutral Ground is zippy and deadpan, clearly indebted to the comedy-news structure of programs like The Daily Show (where, incidentally, Hunt works as a field producer.) The tone shifts in the last third, however, as Hunt reports on the deadly white nationalist march in Charlottesville, Virginia. There, participants have abandoned all pretense about supporting the Confederacy as a legitimate period of American history, and instead have gathered to actively celebrate and promote white supremacy. Hunt, after talking to his father about his newfound rage, ends the documentary by participating in a performance art piece about a slave uprising. Contrasted with his outsider status at the Confederate battle reenactment, it’s a moment of catharsis: here, and for the first time in the documentary, Hunt connects Blackness to individual and collective agency rather than trauma and abuse. For Hunt, Blackness doesn’t have to be, and in fact shouldn’t be, defined by pain or anger. Equally important are moments of hope and joy, as illustrated in the documentary’s final montage of Confederate statues being toppled around the country. “Symbols represent systems,” an activist tells a crowd of protesters in New Orleans. Hopefully, we as a nation will recognize that the symbolism of a Juneteenth holiday carries as much weight as the removal of brass and stone, and erect new systems accordingly.

Writer: Selina Lee

BITCHIN’

He’s Rick James, bitch, and there’s a great new documentary about him by Sacha Jenkins fittingly titled BITCHIN’: The Sound and Fury of Rick James, which delves into the wild, complicated life of the innovative and influential musician who coined the term “punk-funk” to describe the eclectic ingredients that went into his unique sound. Jenkins meticulously reveals the deeper layers behind the caricature of the Chappelle’s Show piece that brought James back into the public consciousness shortly before his death in 2004. Jenkins last appeared at Tribeca in 2019 with the documentary TV series Wu Tang Clan: Of Mics and Men, which covered the fabled hip-hop group’s origins on the rough streets of Staten Island; Rick James grew up in a similarly crime-ridden environment in New York, but many miles upstate, in the racially segregated Buffalo of the 1950s. The sexual and criminal exploits that consumed James later in life were rooted in his childhood, as a street kid introduced very early to numbers running and petty theft, as well as the drug abuse that would eventually bring about his demise. He also developed an extremely warped view of male-female relationships by witnessing his mother’s physical abuse at his father’s hands, and by being sexually assaulted by an older woman as a preteen.

However, James’ youth wasn’t all sex and crime — there was also music, of course. The strongest passages in BITCHIN’ detail the long, twisting road to the stardom he finally achieved in the late 1970s and early 1980s, a road that included a notable detour through Canada in the 1960s, where James fled after going AWOL from the Navy. There, he immersed himself in the Toronto folk/psychedelic rock scene, where he rubbed shoulders with the likes of Joni Mitchell and Neil Young, with whom he formed a band called the Mynah Birds, and which later went to the States for a brief, unsuccessful stint at Motown. After running afoul of a Motown exec who learned he was a military deserter and ratted him out to the authorities, James spent a year in prison. Upon his release, he moved to California, where he played in a series of rock and funk bands, without much success. It wasn’t until the late 1970s, when James moved back to Buffalo, formed the Stone City Band with local musicians, and synthesized his myriad musical influences into a singular sound that he finally found the fame that had so long eluded him. James’ success culminated in his seminal 1981 album Street Songs, which included the massive, immortal hit “Super Freak,” which combined an insanely funky riff with the synth-based new wave sound currently in vogue.

As much as the film celebrates and closely analyzes James’ music, it also doesn’t shy away from examining the darker side of his achievements: the Dionysian rock star excess that found him consuming massive amounts of cocaine and other substances, as well as the physical and sexual abuse he inflicted on women. Ironically, James spent much of his peak commercial period writing and producing for women artists such as Teena Marie and the Mary Jane Girls, and in an archival interview in the film, James offers the deeply disturbing self-analysis that it was his abuse of women that gave him insights into writing songs for them. That’s all to say, BITCHIN’ excels in delivering a warts-and-all portrait of its subject, neither descending into abject hagiography nor outright damning its subject with easy moralizing. As such, it reclaims the memory of both the great musician and the troubled human at the artist’s core from being simply a source of cheap punchlines and glib catchphrases.

Writer: Christopher Bourne

The Ballad of a White Cow

Reminiscent of Mohammad Rasoulof’s There Is No Evil — another Berlinale competition title that aptly took to task Iran’s capital punishment apparatus — The Ballad of a White Cow shares a unique amount of its contextual DNA with other notable critiques on the death row complex. Funded by the French company Caractères Productions as an effort to address ethical issues situated behind Iran’s censor-heavy political system, Maryam Moqadam & Behtash Sanaeeha’s latest feature is surprisingly restrained relative to some of its like-minded cinematic fellows. The film’s lack of an overt bite can perhaps be understood as a coupling with its calculated direction, each scene — and even the camera’s maneuvering — progressing at a glacial pace, creating an atmosphere that is both suspenseful and intimate.

A less generous reading would say that it could also be due to the film’s pedantic obsession with casting on-the-nose metaphors and other obvious storytelling devices that merely distract from its essential thesis. The subtext here is hardly subtle: Ballad of a White Cow frequently features obvious visual allusions (including the presence of a literal white cow in the film’s opening shot), which often works to diminish the film’s character dynamics and melodramatic stakes across its dialogue-heavy runtime. This lack of tonal self-awareness results in a mostly sanitized portrayal of its urgent subject matter, the film’s impact lessened through its refusal to pare down its filler in favor of further emphasis on scenes of emotional devastation.

The film’s structure can still be appreciated on a technical scale, including its consistent narrative allusion to Al-Baqara, the Quran’s longest chapter. Moqadam and Sanaeeha utilize verses found in there as a means to offer direct contrast of the morally dubious facets of Iran’s present legal system with Al-Baqara’s legal & humanitarian guidance, and through this juxtaposition The Ballad of a White Cow manages to provoke intriguing, culture-specific discussion regarding the ethical grounds of capital punishment. But none of this would succeed to the degree that it does without Maryam Moghadam’s commanding performance; her delicate, soft-spoken line deliveries communicate an organic, palpable melancholy, while her nonverbal work — mostly seen in the tragic, tense posture she holds — never allows the internal anxiety of the film’s central perspective to relax.

On the strength of its intelligent narrative design and ultimate tonal inflections, then, and despite its considerable deficiencies of visual storytelling, The Ballad of a White Cow remains mostly riveting melodrama, invested as it is with various moral complexities. With two films tackling the same Iranian systemic grievance now released in quick succession, the hope is that such attention signals a shift to come, and that such texts both work to incite change and can eventually become an empowering learning tool for Western viewers. As much as The Ballad of a White Cow is a work of fiction, it’s also, in a more important sense, a document of historical record. Despite its assorted limitations as a film, its strengths should situate it as an important footnote in the rhetoric and eventual revocation of Iran’s death sentence system.

Writer: David Cuevas

Comments are closed.