Junk Head

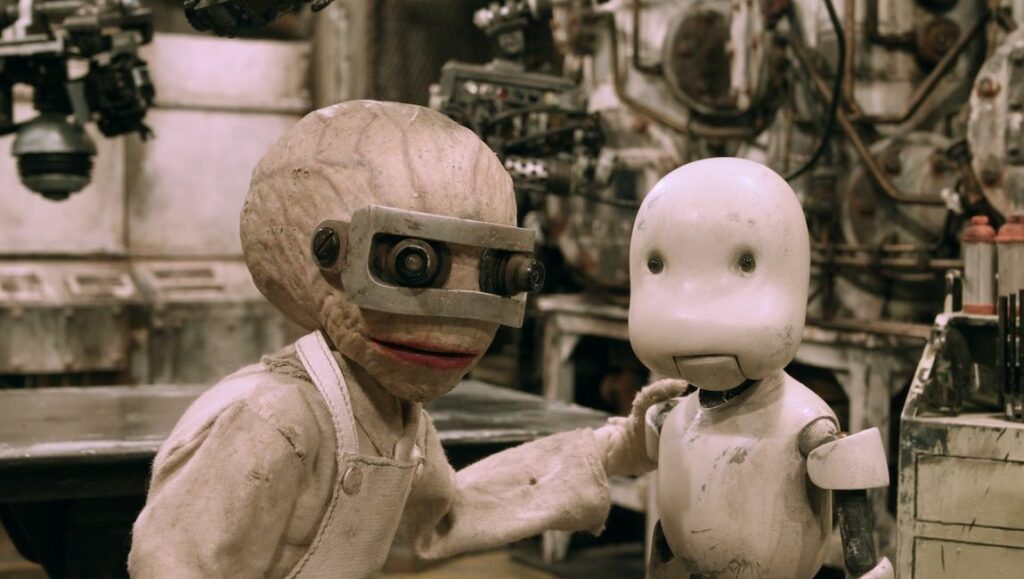

A stop-motion animated epic over seven years in the making, Junk Head is the work of one obsessively dedicated man, Takahide Hori. An interior decorator by trade, Hori embarked on his passion project with no formal filmmaking training, inspired by the homemade computer animations of Makoto Shinkai (best known for the blockbuster anime Your Name) and a desire to do something productive with his nagging artistic impulses. Hori began Junk Head in 2009 as his own director, cinematographer, sound designer, and puppeteer, going online to learn how to make malleable figurines, and finally released a 30-minute short film titled Junk Head 1 in 2013. The short garnered Internet acclaim and a very vocal fan in filmmaker Guillermo del Toro. After securing additional funding, Hori continued working on the project: he finally enlisted some outside assistance and eventually released a feature length version in 2017 (IMDb lists that version as 115 minutes long). Now, a newly edited version is being released, clocking in at slimmer 100 minutes. It’s hard to discern exactly what’s been trimmed in this new, shorter version (being touted as “leaner and meaner” by festival press), as there’s little traditional narrative to speak of. What is here is an abundance of outlandishly wild imagery, breathtakingly creative and frequently disgusting in equal measure.

A brief opening scrawl sets up Junk Head’s dystopian future scenario: As humans developed gene therapies to prolong life, they eventually lost the ability to procreate. Mankind created “marigans” as slave labor to work underground, but they revolted and fomented a rebellion. Now, 1600 years in the future, a virus is wiping out what’s left of humanity above ground. In an effort to study marigans and their reproductive abilities, scientists have launched an ecological surveyor deep underground to understand these creatures and the society they’ve built. It’s a lot of information to take in, and Hori doesn’t seem particularly concerned with providing a full taxonomy of all the strange creatures that he’s populated his film with. Instead, the audience stumbles around this labyrinthine underworld with our intrepid explorer, who is tasked with finding a genetic sample from a marigan reproductive organ.

And what an underworld it is: equal parts Metropolis, Blade Runner, and Eraserhead, with a healthy dose of Cronenbergian body horror. It’s also quite funny, pitching its weird blend of cyber- and steam-punk as absurdist comedy. Like a lot of Japanese animation, there’s a fascination here with combining the organic and the mechanical. A psychoanalyst would have a field day with all the climbing in and out of orifices, as the explorer is constantly sucked into and expelled out of cavernous spaces. Our explorer encounters all manner of life forms, humanoid and not, and transfers consciousness between various robotic bodies several different times. It’s a wild ride, all improbably hand-crafted by Hori. His models are elaborately detailed hermetic worlds, every square inch covered in rich textures and complicated lattice works of tubes, pipes, screens, and rubble (there are some optical effects here and there and a few CGI shots of fire, smoke, and dust, but everything else is a physical object). Noseless human clones rub shoulders with the marigans, weird creatures that look like a cross between big-toothed snakes and the Chimeras from Resident Evil. Dune-esque worms dig through walls and leave red, vein-like webbing to ensnare their food. Phallic appendages are used as both food and currency, and armless, legless torsos that grow tumorous pustules are arranged like cooped up chickens.

There’s an endless variety of stuff, all of it viscerally tangible. Shooting on large sets allows much of the film’s lighting to be practical, creating real shadows and adding volume to individual objects. As more than a few critics have noted, Junk Head frequently gives the impression of a big kid playing with their toys, mashing them together and ripping them apart with equal aplomb. The film does occasionally feel childish, but in a good way; mostly freed from narrative constraints, Junk Head oscillates wildly from the grotesque to the cute, including its very own version of Minions and a bevy of chittering critters that coo and squeak like a child’s favorite stuffed animal. A little of this sort of thing can go a long way, and some of the vignettes are more successful than others. Indeed, even in this shorter version it’s an exhausting experience. Still, there’s much to admire here, and fans of adult animation absolutely cannot miss it. Hori is the real deal; let’s hope next time it doesn’t take him quite so long to make another film.

Writer: Daniel Gorman

Pompo the Cinéphile

Takayuki Hirao‘s Pompo: the Cinéphile is like Vincente Minnelli’s The Bad and the Beautiful, but anime. Imagine that film, but instead of Kirk Douglas’s brilliant sociopath as a producer you have a diminutive anime girl named Pompo who bursts into every room she enters announcing “Pompo is here!” Imagine Bad and the Beautiful not as a wicked satire of the phoniness and self-destruction and cruelty lurking beneath the silvery surface of the dream factory, but as an earnest expression of the power of movies to change lives for the better, and of the soul-inspiring work it takes to create true art. Pompo is a Bad and the Beautiful that actually believes in the movies and all they stand for, a movie that loves the cinema more than life itself. And a movie that truly understands that Cinema Paradiso is super boring.

Pompo is the writer-producer behind a successful B-movie studio. She assembles a young director, an inexperienced actress, and a long-retired star to make the kind of movie that wins a bunch of awards, a heart-warming story about a depressed conductor who learns to love life, and thus be able to make great art again, through friendship with a free-spirited mountain girl. The first third of the film uses a variety of flashbacks to establish the backgrounds of the major figures, the second the shooting of the movie, the final third the life-and-death struggle that is the editing process. Curiously, the three main characters (producer, director, actress) are all ambiguously aged, shorter- and younger-looking than all the other, more adult characters. This is a kind of anime convention I can’t say I understand. It might be something as simple as the idea that the various coming-of-age emotions the film requires the characters go through are externalized in their physical appearances: They feel young, they still have much to learn, and so they look young. Regardless, it’s one of those weirdly unrealistic anime touches that you’d never see in a Hollywood movie that works really well.

Admittedly though, it works better when the artists are actually teenaged, as in the similarly themed but much thornier 2020 series Keep Your Hands Off, Eizouken! by Masaaki Yuasa, which is about a team of high school girls who work together to make an anime short. Like Eizouken, and seemingly most successful slice-of-life anime, Pompo was originally a manga, and it might be more suited to that format, where the clumsy feel-goodness of its conclusion is more balanced by its real strengths, namely its visualizations of the creative process. The director imagining himself slicing film strips with a laser katana while editing (despite the fact that all his editing is digital) is fun, and his recognition of the beauty of the expression on the face of his future leading lady as she unselfish-consciously hops through a puddle is worth more than all the conclusion’s well-meaning speeches about the power of cinema.

Writer: Sean Gilman

Frank and Zed

An astounding six years went into the making of Frank and Zed, writer-director Jesse Blanchard’s magnum opus of friendship and bloodshed. But this is no ordinary feature film, as Blanchard employs an all-puppet cast in telling his tale; the sets have all been meticulously crafted by hand, while the majority of the effects are practical, save for a few brief moments of CGI sprinkled throughout. While it would be easy to label the movie with a catchy logline like, “Jim Henson meets Evil Dead 2,” that would also be both a tad reductive and a great disservice to the obvious love and attention to detail present within each frame of its 95-minute runtime. On a technical level, Frank and Zed is an utterly stunning achievement, the kind rarely aimed for (let alone achieved) in present-day film, audacious and ambitious, even as it notably cribs from some of history’s more famous horror and adventure stories to deliver a final product that occasionally feels a little derivative.

As the yarn begins, an ancient village is plagued by a demon, one whose impending rage can only be stopped through a nefarious deal that will bring about an “orgy of blood” once the king’s bloodline comes to an end. That may happen sooner than expected due to the Machiavellian maneuverings of the King’s duplicitous underlings. Meanwhile, on a castle high on a mountain at the edge of the village, Frank, a creature not unlike Frankenstein’s monster, and brain-chomping zombie Zed have carved out both a friendship and an existence that soon become threatened when their paths cross with those of the violent townsfolk. The film’s resulting conflict, then, demonstrates what a feast for the eyes Frank and Zed is, each shot presenting yet another opportunity to take in the rich detail of the handmade sets and puppet cast, and the material is communicated with tongue planted firmly in cheek, tonally reminiscent of something from the likes of Troma. An example: each time an animal or human character dies, its eyes are replaced with little black Xs. Elsewhere, the phrase “orgy of blood” is hilariously repeated roughly 200 times. And Blanchard certainly doesn’t skimp when it comes to his main event, devoting 30 minutes to over-the-top bloodletting and brutal mayhem. Indeed, any conceivable act of violence you can dream up is perpetrated on these poor puppets, including decapitation and disembowelment. Each one of these barbarous incidents is accompanied by gallons upon gallons of fake blood, spurting and flowing across the screen like a sanguine river.

If it all becomes a bit much after a while, the saturation becoming somewhat numbing, it’s largely balanced by the film’s beating heart: the central friendship between its titular characters, one which engenders far more sympathy than any viewers are likely to anticipate given its broad conceit. There are pangs of genuine emotion as Blanchard’s tale comes to its bittersweet close, exhibiting a pathos most filmmakers can barely accomplish today with a flesh-and-blood cast, a quality that takes Frank and Zed from mere novelty to something altogether more affecting. Come for the technical wizardry and puppet eye-gougings, stay for the love — love of friends, love of storytelling, love of the creativity and freedom found within the medium of film itself. In a culture of retread, it’s nice to be reminded of that fact every now and again.

Writer: Steven Warner

Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist

On August 24, 2010, legendary filmmaker, screenwriter, and manga artist, Satoshi Kon passed away unexpectedly at the age of 46, shortly after being diagnosed with terminal pancreatic cancer. His efforts were always critically-acclaimed, even if they never quite achieved the same level of success at the box office, but the composition of his artistic works, relatively brief though his catalog is, shows his diversity — a handful of comics, four feature films (Perfect Blue, Millennium Actress, Tokyo Godfathers, Paprika), one short (Good Morning), a TV series (Paranoia Agent), and sadly, his final, never-realized project (Dreaming Machine). That’s to say, the reach of Kon’s creative legacy and influence is mammoth, specifically in the history of animation and more generally in the history of Japanese cinema. As a noted perfectionist and eccentric visionary, described by the Japanese producer Taro Maki as “a genius and a nasty guy,” or else characterized in the words of Paprika voice actor Megumi Hayashibara as “absolutely charming, very calm” and yet “impenetrable,” Kon stands out as a fascinating, mercurial figure ripe for study. And that’s precisely what French filmmaker Pascal-Alex Vincent set out to do in Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist, shining a light on the man’s peculiar character and singular world nearly a decade after his tragic early death.

A quick glance at the massive list of various luminaries, including both Kon’s domestic and non-Japanese friends, collaborators, and fellow directors, who agreed to be part of Vincent’s film is perhaps enough to appropriately measure the scale and scope of Kon’s rich and fruitful heritage. The influence the director cast is evident even if Vincent’s documentary remains less imaginative than its subject: The Illusionist is a conventionally-structured, quite straightforward biopic-style documentary, narrated in chronologically linear fashion, and mostly dependent on talking-head interviews. Nevertheless, the film still manages to play out as a respectable enough tribute to the art and work of Kon as seen through the eyes and recollections of the interviewees, though it’s a little confusing why this is all the further Vincent seems willing to push; for instance, he never really dives into the artist’s early influences, his upbringing, or experience as a child and teenager, and any archival footage from the artist himself is relatively scant — whether this was a deliberate structural or conceptual strategy or if it was rather because of limitations in access to the reclusive virtuoso’s first-hand work isn’t clear.

What becomes clear, then, is Vincent’s strategy to focus mostly on film-by-film analyses: he supports this mode with myriad conversations, affording viewers with the requisite contextual information (about people and cultural aspects that may not be familiar to non-Japanese viewers) and some exciting stories about both Kon and the worlds he created. In other words, standard, necessary stuff, but hardly inspiring. And so, regardless of all of the evident effort that has gone into this homage documentary, it’s not exactly unfair to say — particularly if viewers are to be at least half as demanding as Kon was, always holding the highest standards — that The Illusionist feels too hastily executed and lacks the verve and creative playfulness that would have made for a much more enthralling and revelatory experience, and which would have been more reflective of Kon’s spirit and imagination. Indeed, Satoshi Kon is at one point here described as “half-crazy,” and Vincent’s portrait-doc simply functions a bit too timidly to live up to that descriptor. That said, Satoshi Kon: The Illusionist still offers plenty for anime aficionados and cinephiles, and it’s perhaps best to consider Vincent’s work primarily as a friendly farewell feast, not only celebrating and honoring the passionate life of an incomparable artist — whose last words were “I loved the world I lived in. Just thinking about it makes me happy.” — but also managing to suggest a path forward for future generations of animators and filmmakers. The Illusionist is, on top of anything else, an enticement to return to Kon’s work, to attentively revisit the artist’s profound magic. Vincent may not have managed to translate such lessons to his own film, but his invitation is one well worth receiving.

Writer: Ayeen Forootan

Brain Freeze

Although shot before Canada went into lockdown, Brain Freeze is the rare film that benefits from being mapped onto the COVID-19 pandemic. Seen in the light of real-life disaster, its shallow and familiar political messaging might seem relevant rather than simply standard fare for a zombie movie, the genre being, almost as a rule, interested in the concept of quarantine and cynical about governmental crisis response. To accuse Brain Freeze of having no new ideas, though, might be a useless stab at taking the entire subgenre to task. After all, when was the last time there was a vital new twist on the formula? But while the zombie film is itself a shambling undead recycling of old ideas, that doesn’t mean it’s been wrung of all possible fun. Unfortunately, Julian Knafo’s film is neither novel nor exciting, a slick but bog standard horror film of pat commentary and nearly devoid of thrills.

The wealthy Québécois inhabitants of Peacock Island — so named for its peacock population, which, disappointingly, do not get zombified during the film — wish to play golf year round and, to that end, the M Corporation has invented a fertilizer that keeps grass growing in the winter. That fertilizer gets into the water supply and starts turning the islanders into zombies, ones that grow grass out of their skin. Andre (Iani Bédard), the teenage son of a girlboss type go-getter, reluctantly teams up with Dan (Roy Dupuis), an out-of-towner who works security on the island and listens to the conservative talk radio program that constantly disparages Peacock throughout. The leisure of the wealthy creating a zombie pandemic and bringing together people from both sides of a class divide is a fine set-up for class-conscious comed, but Brain Freeze is routinely unfunny and unfocused, refusing anything really biting at every turn. One joke about the zombified staff of the country club seeking unionization merits a brief chuckle, but most of the film’s humor suffers from a total lack of perspective, not to mention a near absence of anyone not from this wealthy community. Duller still are the zombie attacks themselves, staged and executed with little flair and relative bloodlessness, especially as the plot becomes more convoluted, even incorporating sexy twin assassins working for the corporation. A zombie dog here and a zombie infant there are about as creative as Brain Freeze gets, so it’s a lasting shame that it never delivers on the peacocks.

Writer: Chris Mello

King Knight

Writer-director Richard Bates Jr. made a bit of a splash in the indie horror scene with his debut feature, 2012’s Excision, in which a high school outcast obsessed with medical surgeries navigated the pangs and pitfalls of adolescence while on a quest to lose her virginity. Equal parts gory and funny, it marked the filmmaker as a distinct voice in the movie world, portending an adventurous and promising career that unfortunately never really came to fruition. Follow-up features Suburban Gothic, Trash Fire, and Tone-Deaf were met with a collective shrug by critic and audiences alike, each one feeling like an empty bid at legitimacy and, even more distressingly, maturity. Where was the funky free-spirit who successfully mixed sex and amateur surgery and somehow made it both hilarious and horrifying?

Bates’ latest feature, King Knight, does away with the horror angle entirely, setting its satirical sights on modern day woke culture and the hypocrisies that exist beneath its surface. Bates’ pet themes of societal norms and familial strife are on full display, but cloaked in a thick layer of ironic detachment that makes the proceedings feel especially inconsequential. Bates regular Matthew Gray Gubler plays Thorn, a 21st-century witch who leads a California coven with his longtime girlfriend, Willow (Angela Sarafyan). An affable man who sells second-rate handmade bird baths in his spare time, Thorn sees the coven not as an outlet for sinister thoughts and deeds, but as a group that accepts those individuals who feel like outsiders, a place where they can share their thoughts and get their drink on. They wear black not because they are evil, but because it works best with all skin tones. Yet Thorn is hiding a secret from his past, one that will ultimately test the bonds of friendship within the coven, and force him to confront the man he once was, someone he has been desperate to escape.

That synopsis makes King Knight sound far more tonally serious than it actually is, which is as broad as humanly possible. The film may be set in modern times, but it feels like a relic from another era, specifically the mid to late-’90s, where the mocking of both the goth subculture and New Age mysticism were cinematic mainstays. Thorn resembles your basic mainstream goth pop-punk superfan, with his neck tattoos and all-black wardrobe, while Willow burns sage, discusses feminism, and communes with nature. They lead a normal domestic life and talk of their fears of having a baby, but they do it while drinking milk from a horn. The irony is both cheap and hackneyed. These individuals use witchcraft as window dressing, an excuse to be different, but also to befriend other outcasts such as themselves. Bates has similarly good intentions, but never once thinks about the consequences of using his subject in such a broad manner. There is something more than a little insulting in the central premise: that people who practice witchcraft can be normal, too. Bates clearly has a deep affection for his characters, but it is near impossible to determine if he is laughing with them or at them, a fact that makes most of the laughs stick in the throat. Gubler, freed from the shackles of Criminal Minds and network television, gives a game performance, and I will never turn my nose up at an Andy Milonakis appearance. The directing is unsurprisingly energetic, with an animated interlude that feels wholly appropriate considering its Ayahuasca-induced appearance. Yet a film that features Aubrey Plaza voicing a talking rock should be more fun than what is ultimately presented here. King Knight sets its sights on targets that are as broad as a barn, some depressingly so, yet somehow Bates still misses the bullseye. Here’s hoping his aim is better next time out.

Writer: Steven Warner

Comments are closed.