Limbo

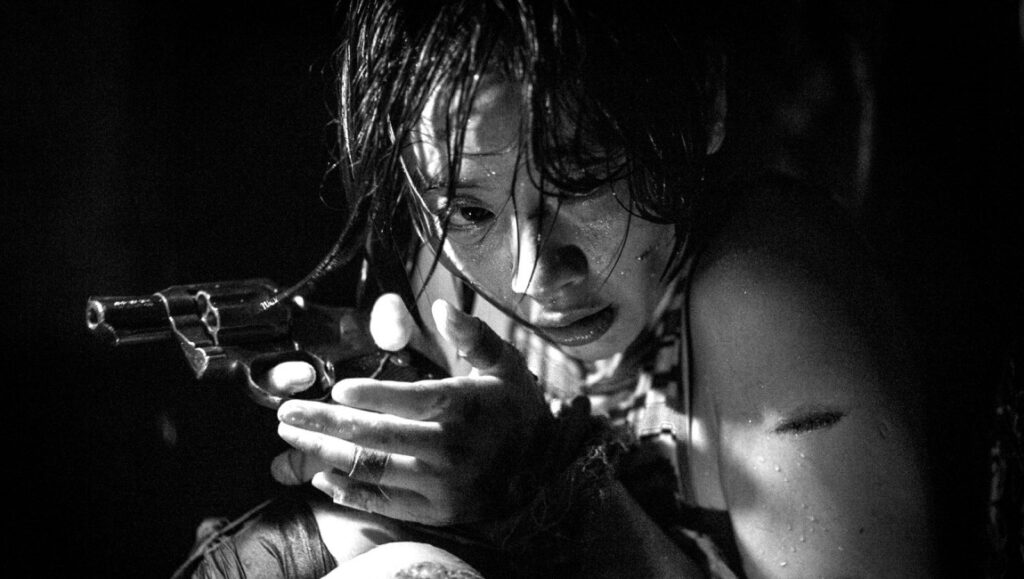

Photography is the first sign that Soi Cheang’s Limbo is different from the director’s past work. Though his return to Hong Kong was bound to retreat from the CGI spectacle of his Mainland-produced Monkey King movies, the stark, extremely high-contrast black-and-white images immediately set it apart from even his more grounded, generally excellent Hong Kong films. This is a film concerned with grime, one that envisions Hong Kong as a labyrinth of garbage-strewn alleyways bursting with junkies, criminals, and hard-edged cops, a region at war with itself in a purgatorial relationship to the Mainland (hence, Limbo), and it’s a film which weaponizes its look to convey its murky theme. Black seems somehow darker than it ever has, as if every cop’s coat or discarded garbage bag was painted onto the screen, and even the lighter parts of the image feel oppressive, like a grayscale molasses through which the film’s cops and drug addicts trudge. Limbo is another impressive work from Cheang, further confirmation that he might be the best Hong Kong genre filmmaker not named Johnnie To, but it is also frustratingly grim, the work of a filmmaker who looks at Hong Kong and hates what he sees. But his vision is too clouded by an incoherent reactionary streak to lead anywhere but the gutter.

Cham Lau (Gordon Lam) is a grizzled, violent police detective on the hunt for a serial killer who’s been leaving severed hands in heaps of trash. Young, by-the-book hotshot Will Ren (Mason Lee), whose youthful naivety is cleverly mirrored by his incoming wisdom tooth — literal growing pains — plays the good cop to Cham’s bad, venturing with him into dark alleys and pleading with him to stop brutalizing their guide, Wong To (Yase Liu), an ex-con whose shared past with the older detective is leveraged against her, turning her into an unwilling informant. There’s plenty of action, all the chases and fights well-directed by Cheang, whose best trick here is an overhead shot that tracks the movements of his characters in mazes of trash, and the procedure of the investigation remains compelling throughout thanks to the director’s masterful tonal control. But watching the continual brutality visited upon Wong To, who is not much of a character despite Liu’s good work, quickly becomes numbing, and the film’s eventual locating of social rot within extreme poverty, mental illness, and immigration comes off as cheap and unenlightening.

That’s not to say Cheang lets institutions off the hook, just that his approach to social criticism is one of full coverage and anger mistaken for insight, but his vision of the police as brutal, power-obsessed assholes doing much more harm than good fares much better than his rote take on drug dealers. In one scene, Ren’s search for his dropped pistol proves to be a shortsighted search to reclaim his power; the murderer he’s looking for walks past him unnoticed, putting the people Ren’s meant to be protecting in grave danger. His adherence to protocol (see: Stray Dog or PTU for more on missing weapons) and the fear of relative powerlessness renders him blind to what he’s actually looking for. He is hardly better than his partner, a cop who gets results through brazen indifference and wanton cruelty, willfully putting Wong To in danger whenever not beating her himself. These are the two forms of policing in Limbo, inexperienced adherence to stricture and plain mean brutality.

More than a decade ago, Cheang made Accident, a thriller of dazzling economy that trafficked in paranoid ambiguity until it pulled the rug out with a bleak, unflinching ending. Now, years and several movies removed, the filmmaker skips the ambiguities and heads straight toward the doom. Totally uncompromised in its relentless grimness, Limbo is the first of Cheang’s films that is hard to like, frustrating in its messaging and its misogyny, but one that is still harder to shake, the pessimistic work of one of Hong Kong’s very best.

Writer: Chris Mello

Hold Me Back

Ohku Akiko’s Hold Me Back is, like her 2017 film Tremble All You Want, a portrait of a lonely young woman whose inner life manifests itself on-screen in fantastical sequences more reminiscent of anime than traditional romantic comedy. Tremble was a kind of musical about a woman trying to choose between a past crush and a new man in her life. Hold Me Back is significantly darker than that, its hero not always safely navigating the borderline between whimsicality and serious mental illness.

Mitsuko is an office worker in her early thirties who lives alone. She carries on long conversations with an entity she calls “A,” which might be her internal monologue, her conscience, an alternate personality, or a kind of guardian angel. She has a crush on a work friend, a younger man she occasionally sees: they live in the same neighborhood and sometimes she cooks him meals which he, being just as socially awkward as her, takes home to eat alone. Notably, Mitsuko does not appear to be painfully shy or incompetent when dealing with other people; rather, she’s just an ordinary young woman, which implies that her loneliness, and the panic and depression it inspires, is not anything all that strange: everyone, at least at times, feels the same way. It’s just that because she’s in a movie, Mitsuko’s emotions manifest themselves in visually imaginative ways.

As such, Ohku’s films have more in common with slice-of-life anime, say the films and TV series by Kyoto Animation (K-On!, Sound! Euphonium, Nichijou) than they do with Hollywood romantic comedy, even in its quirkier forms, like the films of Michel Gondry, or else the entire manic pixie canon. Ohku’s fantasies are not merely funny or weird or beautiful for their own sake (though they are all of those things), but are inextricably tied to the psychological condition of her heroines, women about whose sanity we’re never entirely sure — how much of Mitsuko’s life is hallucination is impossible to tell. We can be pretty sure that a musical sequence on an airplane, set to Otaki Eiichi’s 1981 city pop classic “Kimiwa Ten-en Shoku” (a song also used in Sound! Euphonium), is not real, but rather a manifestation of music’s power to calm Mitsuko’s nerves as she confronts her fear of flying. But how much of her interactions with her would-be boyfriend, then, are fact or fantasy? And is the young man who another work friend has a crush on really as ridiculous as he seems, or is our perception colored by Mitsuko’s bias against him? To this end, Ohku is aided immensely by a strong performance by Non (Nōnen Rena), a model and singer who is probably best known abroad for being the lead voice in the 2016 anime In this Corner of the World (she also stars in Iwai Shunji’s upcoming The 12 Day Tale of the Monster that Died in 8). Non plays all aspects of Mitsuko’s personality straight, bringing a hard edge to the cuteness, and tempering the desperation with reserves of inner strength.

But it remains that Ohku’s films aren’t really romantic comedies. She’s less interested in relationships, or the idea of love, than she is in the ways we deal with its absence, in the ways we’re all alone in our own heads, and the seeming impossibility of therefore connecting with another person. Mitsuko in Hold Me Back seems to break through and find such a connection: the film is, after all, ultimately a comedy. But what lingers most after the music fades is the relatable feeling of her panic, her failures, and her abject, familiar loneliness.

Writer: Sean Gilman

Under the Open Sky

Like R.W. Fassbinder’s Berlin Alexanderplatz, Under the Open Sky opens with an aging man being released from prison after serving thirteen years for murder. During his out-processing, the warden glances through the records and, in perhaps an attempt to relieve their unhappy burden, asks if he feels any remorse over them. The man nods, then clarifies his position — not towards the victim, a common “hoodlum” in his words, but for having suffered because of him. Mikami, ex-yakuza and an unloved social outcast played by veteran actor Kōji Yakusho, has vowed to “go straight” ever since, eagerly rejecting the destiny his orphaned childhood and criminal adolescence might have imposed upon him. But the comparisons to Fassbinder’s sprawling adaptation end here: While Mikami’s infantile disposition, imbued with a gruff and childlike innocence, may resemble Fassbinder’s Franz Biberkopf, the trials and tribulations the two encounter in the civilian world bear few similarities: Biberkopf, a common man, undergoes a hellish descent into madness; Mikami, of the underworld, falls a good many times before suddenly picking himself up.

Miwa Nishikawa’s adaptation of Ryozo Saki’s prizewinning novel, Mibuncho, might not have been dealt the fairest hand by being compared to Berlin Alexanderplatz, at less than a seventh of the latter’s colossal scope and runtime. But comparisons aside, Under the Open Sky still proves an increasingly melodramatic work whose quirky sentimentality, masquerading as endearing complexity, seems destined to win over more hearts than minds. From the outset, Nishikawa’s vision for her protagonist’s surroundings is set in stone: society as a whole may prefer not to reintegrate its transgressors, but everyday pockets of humanity usually respond kindly to those who are genuinely interested in rehabilitating themselves. And so begins Mikami’s upward struggle toward a normal life never known to him — he meets an affable lawyer who sponsors ex-convicts as a hobby, then tries leaving behind welfare and landing a job, getting back his driving license, and finding his mother with the help of a television crew. The inability to temper his angry outbursts, however, sees him rejecting the kindness of strangers, roughing up petty gangsters to within an inch of death, etc. — the hallmark of recidivism, essentially. Yakusho, valiantly injecting earnesty and vigour into his character’s rebirth, remains frustratingly subjected to the film’s saccharine generics. More a tiresome collection of calculated emotional investments than an organically developed storyline, Under the Open Sky initially charts a hopeful path, before going astray towards a checklisted, by-the-book formula and nosediving into an inexplicable and unsolicited denouement. There’re only so many bumbling, unhinged, self-pitying tales the genre can take.

Writer: Morris Yang

Over the Town

Unlike the booming fame and splendor of Tokyo’s Shinjuku and Shibuya districts, sister neighborhood Shimokitazawa is most well-known among the young locals for its trendy hipster/bohemian lifestyle. Filled with live music venues, avant-garde theaters, cozy cafés, amiable hangout joints, clothing boutiques, and record shops, the rapidly-evolving Shimokitazawa offers not just the milieu of Rikiya Imaizumi’s Over the Town, but in a way, also serves as its main character. Imaizumi, who has quite a reputation (particularly among homegrown Japanese young cinephiles) for his depictions of modern-day romance and the myriad pleasures and hardships of contemporary relationships, returns to the well once more with his latest effort. Here, Imaizumi follows the twenty-something, awkward ex-musician/bookworm/man-boy protagonist, Ao Arakawa (Ryuya Wakaba), who works as a sales associate at a second-hand clothing shop in Shimokitazawa. After his girlfriend Yuki (Moeka Hoshi) breaks up with him, admitting she’s been cheating on him, we see Ao aimlessly walking the streets in a bit of a heartbroken, flâneurish manner, idly spending time in different places or just reading his books here and there. The shape the film takes going forward, then, is as a loosely episodic, interconnected network of random encounters between Ao and different strangers and friends — especially the young women he encounters, including Machiko (Minori Hagiwara), a newbie filmmaker who asks him to play in her graduation film (winkingly titled “Sleep in Reading”), which instills a sort of meta quality to Imaizumi’s work (a seeming trend in many recent Japanese cinematic efforts). This metafilmic wrinkle, working alongside the bold presence of the second-hand shops located in a quarter where the new constantly dissolves the old, offers a precise metaphor for everything the film seeks to capture: a time and place where not only the objects, but also the human subjects and their affairs, emotions, feelings, and imaginations, are of a recycled, pre-consumed mode. For Ao, it takes a small-scale, urban journey to realize the fact that no imaginary or ideal conception of love is possible in the real world.

Imaizumi’s vivid aesthetic relies upon a very unadorned, hyper-realist style to capture the intersubjectivity of his juvenile characters through mainly distant, fixed shots with no interrupting cuts, dedicated fully to the naturalistic dialogues that occasion between these people and which mostly revolve around various aspects of culture, art, and relationships. But of perhaps more salience in Over the Town is the very subtle manner in which Imaizumi renders his film’s lo-fi temperament into a soft, day-dreaming-y ambiance wherein the cringe-comedy quality of the film manifests itself through overtly tongue-in-cheek humor. Unfortunately, the problem is that as the film pushes forward, it begins to gradually disengage the viewer as much of the film’s “action” — mundane conversations, encounters built on naturalistic performances, and the delivery of deadpan jokes — become repetitive and flat, or at least lose their initial freshness and delicate touch. Understandably, Imaizumi has tried to draw some resemblance between his raw, scruffy style and the character of Ao, who across the two-hour runtime never appears as more than an inactive and awkward bystander. That’s to say that Imaizumi’s excessive insistence on neutral visuals and low-key, mumblecore-esque rom-dram texture depletes the film of energy far too soon to remain more engaging than the series of tedious “talk therapy” sessions. This also works to sap the mood and atmosphere of Shimokitazawa which the director so wants to celebrate: to do it justice, Over the Town would have needed much more zip, like in the way that Woody Allen cherishes his beloved NYC on screen, or in the exhilarating but playful manner that Hong Sang-soo explores the nooks of Seoul. It’s evident (and respectable enough) that Imaizumi commits to his deliberately relaxed ethos (though maybe a bit too much), and his down-to-earth aesthetic lands for a while. But ultimately, the film could stand to do with a little bit more of Ao’s idealistic dreaming, as viewers are left to wonder how far above its middling aspirations Over the Town could have risen if it had dispensed with its indulgent, fatiguing realism.

Writer: Ayeen Forootan

Sweetie, You Won’t Believe It

Sweetie, You Won’t Believe It sounds like the name of a failed American sitcom from the ‘50s, and true to that shape, this comedy/horror hybrid from Kazakhstan exhibits the same troubling gender politics that plagued many a production from that bygone era — but with a twist. Dastan (Daniyar Alshinov) is a put-upon husband with a pregnant shrew of a wife who escapes with his two best buds for a guys-only fishing trip that spirals wildly out of control when they witness the shooting of an unarmed man by four local wacky mobsters. As if things weren’t bad enough, they are also being stalked by a one-eyed maniac who is attempting to pick off members of both parties. Think Deliverance meets The Evil Dead, although writer-director Yernar Nurgaliyev pitches the proceedings at a tenor that rockets right past any “live action cartoon” descriptor. There’s also a freneticism on display in the early going that is so off-putting that it borders on tortuous to endure: characters scream every line of dialogue, mistaking volume for comedy; a mob boss speaks only in proverbs; and an overweight man dances and sashays his way into the film in a manner that seems fairly homophobic (he also faints at the sight of blood). But wait, there’s more: when our three protagonists go fishing, their hooks rip off not only one of the members’ pants, but also another man’s ear lobe; ironic needle drops saturate the soundtrack to a degree that could suggest, or at least be misconstrued as, satire, and the violence is ridiculously vulgar, with jaws ripped in half, bodies losing their heads, and blood and piss spraying the camera (within the first 15 minutes, no less). And most importantly, farting plays a critical role.

It’s an exercise in outre juvenalia, to be sure, and the whole thing would be easier to dismiss if Nurgaliyev didn’t display legitimate filmmaking chops, a fact which may sound like putting lipstick on pig, but the formalism demonstrated within each respective shot impresses even as the action continually grates. Nurgaliyev is downright old school in his approach, favoring Steadicam and dolly shots that are a true rarity in a subgenre that emphasizes visual busyness above all else. The widescreen compositions actually utilize the extra space in meaningful ways, capturing both the characters and their environments with the use of deep focus lenses, with foreground and background allowed to effectively play off one another, sometimes even brilliantly, such as an extended bit of physical comedy where one character evades the watchful eye of his captor. The symmetry of Nurgaliyev’s images alone would make Wes Anderson stand up and applaud. It must also be said that the proceedings actually do improve the longer they go on, as the story loses more and more periphery characters and narrows focus to its central trio, who begin to resemble something one could almost describe as endearing. All of this ridiculousness seems to exist solely for the titular punchline at film’s end, a joke as old as a Catskills routine, but it’s still enough to make one question if there may have been actual intent behind the broad caricature. It’s too bad that this late-game realization doesn’t make this any less obnoxious. If Nurgaliyev can move beyond the sophomoric shenanigans of Sweetie, You Won’t Believe It and deliver a project that marries his visual acuity with a story that isn’t analogous to nails on a chalkboard, it will be a day worth waiting for.

Writer: Steven Warner

Comments are closed.