Violet is a distinctly 21st-century woman-celebrating flick, perhaps a bit saddled by its too trite messaging, but still something of a feminist force of nature.

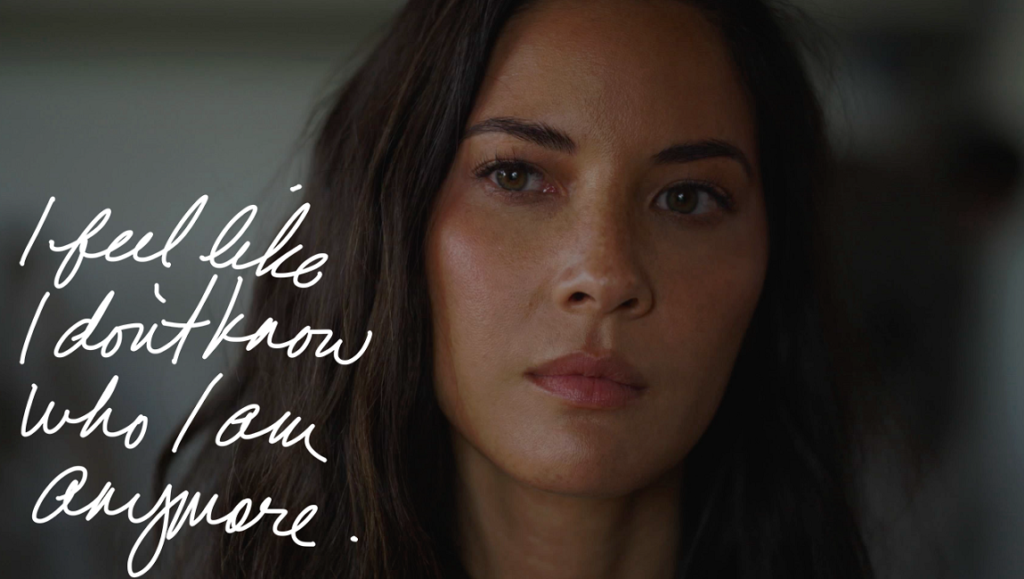

Violet, written and directed by actress Justine Bateman in her feature film debut, is a tale of female empowerment told with a full measure of bluntness. Its opening moments are a flurry of shock cuts depicting decay and destruction. Its protagonist, the titular Violet (Olivia Munn), is a respected film producer who lives her life according to the voice in her head — a man’s voice, mind you (Justin Theroux). He belittles her, tells her that she is a joke and that the world is laughing at her. When she follows the advice of said voice, it inevitably leads to regrettable choices, with her anger and resentment visualized courtesy of a red filter that slowly glows brighter until it blots out the entire image, and accompanied by a droning siren that fills the soundtrack, completely overtaking the dialogue. Her innermost thoughts are depicted on screen in handwritten text, oftentimes contradicting the sonorous voice that consumes her. And to top things off, a memory of the one time she felt freedom in her life — while biking as a child — is often projected on surfaces around her as she desperately tries to regain control of her life.

So, it shouldn’t surprise to hear that Violet isn’t a film the least bit interested in subtlety, but frankly, it’s all the better for it. Violet’s pain is raw, and Munn, in a truly revelatory performance, effectively reveals how Violet’s anger has manifested itself in ways she barely recognizes, rendering her an unwilling spectator to her own life. It’s at the film’s half-way point that Violet finally chooses to wrestle back control, ignoring that Justin Theroux voice in favor of making choices that will truly bring her happiness. And while this conceit is nothing new — hell, even an episode of Seinfeld covers the same territory — the way that it’s presented here is legitimately bracing, as it feels like Bateman is holding nothing back. In that sense, and more than anything, Violet is a rallying cry, a call to arms to women who have been told that they should unquestioningly adhere to what society — read: men — dictates. That is not to say there isn’t a bit of wish fulfillment going on here, as Violet is instantly treated to a fabulous new job and a ridiculously good-looking and supportive boyfriend (Luke Bracey) as a result of her autonomous actions, but Bateman is obviously well aware of this, as it falls consistently in line with the hyper-directness of her messaging. In other words, this is the type of film that you’re either on board with from the word go, or one at which you find yourself standing on the sidelines, marveling at the apparent smugness of it all. But for viewers who find they vibe the material, it will be hard to find fault with its end product, clearly coming as it does from such a genuine place, and anchored by Munn as its humanizing center. Violet is a distinctly 21st-century woman-celebrating flick, perhaps a bit saddled by its too trite messaging, but still something of a feminist force of nature.

Originally published as part of SXSW Film Festival 2021 — Dispatch 5.

Comments are closed.