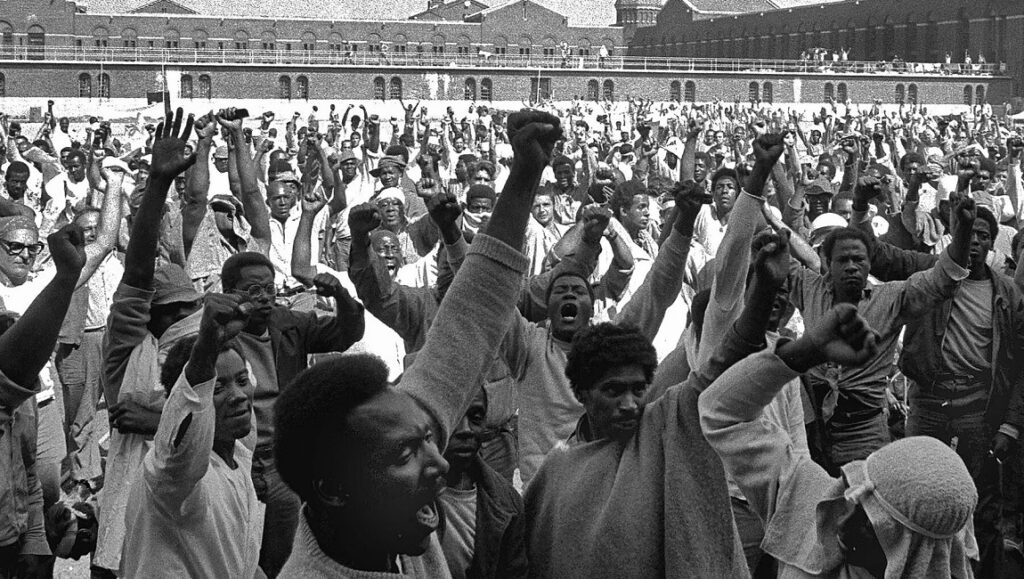

Most people’s familiarity with the Attica Prison Rebellion of 1971 is strictly limited to Sidney Lumet’s 1975 crime drama Dog Day Afternoon, in which Al Pacino’s amateur bank robber can be heard bellowing the famed prison’s name as police threaten to swarm his location. Stanley Nelson’s new documentary Attica attempts to rectify that injustice, shedding light on the five-day riot that saw 29 individuals dead by its endpoint. Nelson wastes no time in setting the scene, throwing the viewer straight into the events that resulted in the 1,200+ inmate population wresting control of the facility from its heavily-armed guards, with 42 correctional officers and civilian workers taken hostage in the process. Realizing they were occupying a rare place of power, the men banded together and attempted to instigate wide-reaching changes within the institution, one nationally known for its poor living conditions and reliance on brute force to maintain order. These individuals were not seeking ridiculous demands — well, not entirely. As several of the former inmates admit, perhaps seeking amnesty through government-funded plane rides to the shores of Cuba was a little far-fetched. But at the end of the day, these men simply wanted to be treated like human beings, afforded the tiniest bit of compassion and dignity. Each of the inmates interviewed deliver their own horror stories of the conditions they endured, how a doctor’s inspection of a head wound consisted of merely administering another severe blow to the affected area, or how the guards would routinely beat and torture those prisoners they found especially problematic — i.e. Black. Make no mistake, Attica is nothing if not a portrait of the systemic racism that allowed a place like Attica to exist in the first place, and operate in the horrendous manner in which it did. The inmates discuss how they had to work together if they ever hoped to get out of the dire situation in which they found themselves, various races and religious backgrounds putting aside their differences in the name of human rights, while the predominately white men of power outside of the facility’s walls conspired to end the situation as quickly as possible, human life be damned; the irony is certainly not lost on Stanley. The prisoners knew that harming the hostages would be a death sentence, and so they did everything in their power to ensure their safety. Negotiations were ultimately held between the rioters and high-ranking officials, with an official observation committee — individuals sympathetic to their cause — brought in to ensure fairness. What ultimately resulted was as shocking as it was inevitable, as state troopers seized control of the facility through deadly means, deploying pepper gas before riddling the captive crowd with thousands of bullets, killing ten hostages and 19 inmates in the process.

Much like his searing 2006 documentary Jonestown: The Life and Death of the Peoples Temple, Nelson manages to take a sensationalistic news story known mostly as a broad-strokes myth and find the human story within. The eyewitness accounts of inmates, news reporters, officials, and family members who were present both inside and outside the walls of Attica lend the proceedings an immediacy that is impossible to shake. Unfortunately, as was also the case with Jonestown, Nelson presents the material in the most pedestrian way possible, a series of talking head interviews and archival footage that is expertly edited together, but does little to distinguish the film from a million other news programs and documentary features clogging the airwaves on a 24/7 loop. Still, there’s no denying the sheer power of some of the footage presented here, especially in the film’s final 30 minutes, as the siege of the compound is shown and detailed with shocking bluntness. The prisoners, humans, were only seeking basic decency; for those that survived, what they received was torture and degradation. Video footage and photographs show rivers of blood flowing over walkways, men forced to strip naked and parade around as they are mocked and ridiculed in imagery that recalls the Holocaust, racial epithets hurled with wild abandon. Screams of, “White power!” fill the air following the assault, while President Richard Nixon himself discusses with New York Governor Nelson Rockefeller how the Black man must be “suppressed.” News reports herald the uprising as “Black-led,” while the prisoners were accused of killing the hostages — a fact later refuted by the New York medical examiner, who insisted they died by gunshot wounds from the officer’s guns. It’s easy to label a film like Attica as timely in this day and age of BLM and ACAB, but it also serves to shine light on an injustice that has been largely forgotten, and misrepresented when not. How can we learn from the mistakes of our past if they are scrubbed from our cultural consciousness? That’s precisely what those in power bank on; luckily, filmmakers like Nelson are out there trying to right such wrongs. The frustration, then, is that his sobering discourse lands with enough power to wish that he had used the film medium in a more distinctly cinematic way.

You can currently stream Stanley Nelson’s Attica on Showtime.

Published as part of DOC NYC 2021 — Dispatch 2.

Comments are closed.