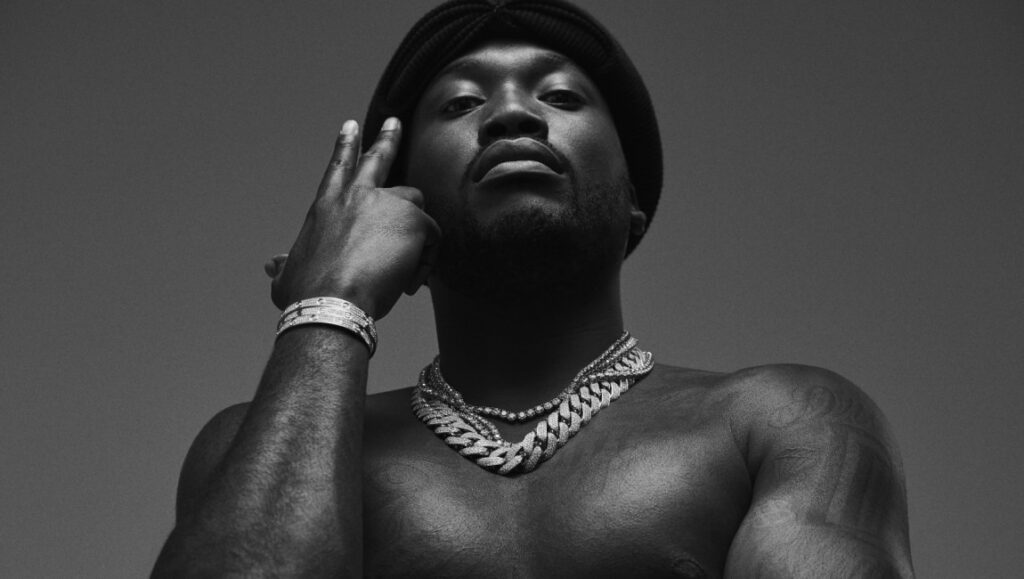

Meek Mill

Meek Mill owes his entire career to fortunate circumstances: as in, he regularly talks a big game online about how he’s one of the “top dogs” of the industry, but it’s difficult to accurately pinpoint exactly where he currently stands within hip-hop culture. His previous studio releases would usually drop right as he was embroiled in some personal hardship, junctures where he could conceivably market himself as an underdog figure — most notably, the major L’s he took from conflicts involving Drake and this country’s racist judicial system. But his latest album, Expensive Pain, arrives with little media fanfare. This time, there’s no real-world context into which one can place Meek’s raps; the resolve he vigorously displayed through assaultive technique, which once worked in his favor based on surrounding situations, now just sounds like he’s going through the motions. He’s now five albums into his lackluster discography, with little differentiation between past releases other than the size of the guest list. As it stands, it often seems as if Meek himself has lost sight of his own narrative, which is a tough position for a rapper of his standing to be placed in: he works best when pushed into corners, when he’s spitting his ass off about the Rollies on his wrist like they’re the last words he’ll ever utter. He’s talented — but only within the right conditions, in short, tight bursts.

But even that aspect of his art seems to be on auto-pilot here: “Intro (Hate on Me)” — which utilizes a obvious, sped-up sample of Nas’ “Hate Me Now” — has the usual Meek Milly stunts and preoccupations that can be heard on his last few boisterous album intros, the only difference being that the fifth time through, they’ve lost their charm. Still, those tracks at least sound like they’ve been assembled with Meek’s sensibilities in mind, unlike the many others that repeatedly prove how limited his artistic range is. He’s a follower, not a leader; when left to his own devices, he’ll gladly co-sign any production style that will guarantee some playlisting. There’s a certain amorphous quality to the way Meek maneuvers through such sonically diverse terrain — undoubtedly a key component to his professional longevity — which makes him something like a jack of all trades and a master of none. But the harder Meek tries to please everyone, the more faceless his music becomes. He’ll record a verse for a piano-heavy track that sounds exactly like five different Lil Durk songs (“On My Soul”) and then shamelessly book him as a guest feature on the very next single. Or he’ll try to sound like a nice guy (“Ride for You”) on an album where the most mature thematic throughline involves distressing over day-one homies trying to fuck his “bitch.” His collab with Giggs is forced and unneeded but could lead to some international cross-over; so thus, like several other throw-away titles here with big names attached (Moneybagg Yo on “Hot,” A$AP Ferg on “Me (FMW)”), it remains. In all of these regards, Expensive Pain serves as a testament to the aforementioned circumstances of one Robert Rihmeek Williams: without external conflict motivating him, he’s unable to meet even the most basic of standards.

Writer: Paul Attard Section: What Would Meek Do?

The War on Drugs

Despite the out-of-time quality of their music, the origins of The War on Drugs — the studio project of musician and producer Adam Granduciel — embody with exactitude their moment of conception. The group’s debut album Wagonwheel Blues arrived near the tail-end of the 2000s, a now-bygone era during which a sea change in critical sentiment was afoot in favor of more vibe-centric, production-forward records like Animal Collective’s Merriweather Post Pavilion and those within the “chill-wave” movement. With their beguilingly hazy production aesthetic, and arguably the parallel rise of a music festival economy that could platform it, The War on Drugs was especially well-suited to impress in that moment, releasing sophomore album Slave Ambient to acclaim and its follow-up, 2014’s Lost in the Dream, to numerous “best of the year” accolades. In these respects and more, The War on Drugs have become something of an American rejoinder to Tame Impala — another one-man rock outfit whose act of creation is a simultaneous act of musical remembrance — with the subject of that project’s revival (‘60s psych rock) replaced with the heartland rock of the 1980s. And indeed, The War on Drugs seem poised to join Tame Impala among rock music’s more commercially viable groups, if the band’s upcoming tour stops (among them, Madison Square Garden) are any indication. Yet I Don’t Live Here Anymore — the new record that nominally enshrines this A-list ascendancy — is ill-suited to usher in this narrative climax, presenting an unsuccessful refinement of the group’s earlier charms that evinces little rope left in their core concept.

The seeds of diminishing returns were arguably planted on 2017’s A Deeper Understanding, an accomplished record whose impressive scope and production fidelity made it easier to forgive occasional “been there, done that” moments. The slick, comparatively stripped-back IDLHA hides even fewer of these shortcomings, baldly offering up the usual musical reference points (Springsteen, Mellencamp) and lyrical subjects (personal chaos communicated through elemental signifiers) that have characterized every War on Drugs release to date. An ostensible change-up is signaled via the restrained balladry of opener “Living Proof,” though lyrics about staying true to oneself amidst unrecognizable circumstances ring all too familiar (and the platonic ideal of “War on Drugs album-opener” is satisfied by the next song “Harmonia’s Dream” anyway). With its explosive group chorus and searing guitar heroics, IDLHA’s title track and album centerpiece suggest catharsis that ends up similarly undercut by the song’s resemblance to Deeper Understanding highlight “Strangest Thing.” The lack of novelty extends beyond direct one-to-one song analogues and dictates the form of the album: static synth passages which long outstay their welcome (“Change,” “Victim”) and played-out sequencing choices like the album’s closing one-rocker/two-ballad triad (mirroring the concluding arcs of War on Drugs’ two previous releases). If perhaps a minor-seeming gripe, the limited bag of tricks exposed on IDLHA is especially frustrating in the context of a project whose musical imprint was already plenty iterative to begin with. Rather than the storied canon that War on Drugs pulls inspiration from and once seemed poised to enter, IDLHA simply recalls the superior War on Drugs music that preceded it.

Writer: Mike Doub Section: Ledger Line

JoJo

JoJo’s 2020 album Good to Know wasn’t a comeback, exactly — her real comeback was 2016’s Mad Love, her first studio album released since escaping her contract with the infamously terrible Blackground Records — but Good to Know still felt like a stronger re-establishment of her artistic voice and vision than anything that had come before. Unlike the poppy singles of Mad Love, its songs leaned fully into R&B, sampling a diverse array of styles and moods while still adding up to a vibrant, cohesive whole. October’s Trying Not to Think About It (which is somewhere between EP and album) feels like an appropriate companion project: same excellent vocals and rich R&B production, but more consistently somber and introspective, focused on themes of depression and anxiety.

While Good to Know feels like a collection of songs (albeit an excellent one!) that plays just as well on shuffle, Think About It was clearly designed to work best as a front-to-back listen. The mood is consistent (anxious, searching, musically minimalist), the songs transition into each other smoothly (the interludes are just as important a part of the album experience), and the structuring is patient (there are plenty of long outros and instrumental breaks between songs). As a result, a full listen feels impressively immersive. This is a project that, like the album cover depicts, sounds most suited to late nights laying alone in bed, stuck in your head and struggling to fall asleep — although the minimalist, vibey R&B production would work in more positive settings, too.

The arrangements here are simple, soft, and vocal-forward, focused on quietly evoking a mood in the background while letting JoJo shine. JoJo’s greatest strength is her intelligence as a vocalist: it’s one thing to have a great voice and another thing completely to know how to use it, when to be subtle and impress with quiet control vs. when to go big and make a moment of vocal acrobatics feel earned, and her work in the past two years has demonstrated this over and over. For instance, her belted high notes on the standout “Feel Alright” sound thrilling, but on the following track (“Fresh New Sheets”), her hushed, low-key melodies are just as emotive. Harmonies and background vocals are another highlight of the project, with vocal layering acting like an instrument in itself.

Trying Not to Think About It is overwhelmingly inward-looking, barely tethered to the outside world, and so many of its songs feel as if they’re teetering somewhere on the line between dream and nightmare (“Holding on to the edge of a knife / Just to feel alright,” she sings on “Feel Alright”). It’s not the kind of album that’s concerned with catchiness or big pop moments, but, despite that, there are still a few fun instances to be found (relatively speaking). “Spiral SZN” is genuinely upbeat, as long as you can take its catastrophizing lyrics in stride, and although lead single “Worst (I Assume)” is one of the less sonically interesting songs on the project, it does have one of the more memorable melodies. The simplicity of its production lets JoJo play around more with her delivery, swinging rhythms and exaggerating highs and lows in order to emphasize her confessions of self-sabotage (or maybe to disguise them?).

Taken together with Good to Know, Think About It feels like the second half of a complete whole. While the former re-asserted JoJo’s ear for R&B and proved that she could put together a great album consisting of individually strong songs, this new release shows that she is just as capable of crafting a cohesive album around a single organizing concept. JoJo — finally — is here to stay.

Writer: Kayla Beardslee Section: Pop Rocks

Natalie Hemby

You probably know a lot of Natalie Hemby songs, even if you don’t know that they are Natalie Hemby songs. To call her either a game collaborator or a go-to hitmaker would be selling her short; for a decade and a half, she has straddled the line between country music’s mainstream and its margins better than almost anyone, cowriting banner songs with the likes of Keith Urban and Sunny Sweeney, Kacey Musgraves and Brothers Osborne. (She may also be the only person whose writing credits adorn the albums of Amy Grant and Lady Gaga.) Following her turn in the limelight as one fourth of The Highwomen, Hemby truly comes into her own with Pins & Needles, an album that might as well be her solo debut, 2017’s self-released, under-the-radar Puxico notwithstanding. At once confident and modest, eclectic and intimate, it’s an album that eschews many of the trappings of the long-anticipated-solo-record, and it’s better because of it. There’s no grand conceit here, no extensive backstory, no obvious autobiographical skeleton holding these songs in place. Instead, Pins & Needles plays like a rowdy collection of singles, a pristine portfolio from a woman who just loves writing songs. In a way, maybe that’s all we need to know about her.

Though not pitched explicitly as a memoir, Pins and Needles does behold Hemby in full flourishing. Everything that makes her a special talent is represented here, starting with her zeal to collaborate: The heart-fluttering, pace-quickening title song is a co-write with Brothers Osborne, while the driving “New Madrid” shares a byline with the great Canadian troubadour Rose Cousins. “Banshee,” an irrepressible confection of whistling and synths, boasts a songwriting credit from Miranda Lambert, perhaps the biggest marquee name you’ll find on Hemby’s resume, but the song also speaks to Pins and Needles’ ace in the hole: Producer Mike Wrucke, who also happens to be Hemby’s husband. He brings texture, color, kinetic energy, and a palpable sense of fun to the whole record, fleshing out Hemby’s grounding in country but also her affinity for late-’90s roots-rock a la Sheryl Crow. (Hemby has half-jokingly referenced this album as her tribute to the glory days of Lilith Fair.) If you thought The Highwomen just a shade too austere, Pins and Needles offers one remedy after another: The boisterous banjo stomp in “Hardest Part About Business,” the lovelorn stutter in “Radio Silence,” the good-natured jamming in “It Takes One to Know One.” These vivid accoutrements enliven songs about love and heartbreak, the risk of meeting your heroes and the perils of sudden success, and they ensure that Pins and Needles feels like the bright, personable, star-making turn that Hemby deserves.

Writer: Josh Hurst Section: Rooted & Restless

Geese

Fresh out of their senior year of high school, Geese comes ripping onto the scene with their buzzy debut Projector, a post-punk album replete with all the genre’s classic elements. A few surprises are immediately in store for anyone coming in blind: first, that this confident work is a debut album, and additionally that it’s landing in 2021 and not 2001, with its grimy rock sounds sounding closest to the early New York indie scene. It might be a futile vibe to catch, as it revisits a cultural moment that came and went before the band members were even in kindergarten, but in its pursuit, Geese makes something that can be considered relatively interesting at the very least.

Were you to distill the sound of every popular rock outfit of the early aughts, you would notice a few similarities. From muted guitar tones to mucky frontmen that look freshly plucked from the gutter, there’s plenty of obvious overlap. While Geese does tend to lean directly into these clichés, there’s a reason they’re so drawn to them, and a reason they so resonated in the first place. In a world of polished pop stars and the gross misuse of nostalgia (looking at you, Greta Van Fleet), it’s almost refreshing that a group of late-teens are trying to remake something akin to Is This It. The biggest detriment to this approach is that such an effort will make it as far as mimicry, stopping short of adding any new songwriting elements, and it’s here that Geese elevate themselves to some degree, distinguishing their tracks a bit by imbuing them with Talking Heads-style hooks. Sure, it’s but another bit of derivation, but the blend of these two classic sounds ends up endlessly listenable and certainly worthy of a foot tap or two. It also benefits the band greatly that they are all already experts at their respective instruments, opting for a tighter interpretation of the loose-sounding bands they sonically reference. Still, this kind of work has a definitive ceiling, and Geese repeatedly hit it without ever managing to break through.

There’s a conversation to be had about “bringing back” an era of music in the modern age. It seems not particularly long ago that Geese would have been heralded as instant greats, propelling them to an unbelievable degree of stardom. Now, they seem quirky, a band destined for the worst people possible to point to and say “Look at these guys, making REAL music.” Obviously, speaking to this insufferable demo isn’t the band’s fault, as they clearly are just playing what they love (and doing it well), but it does leave an unfortunate after, whether intentional or not. But setting that extra-textual cynicism aside, Projector is a worthy introduction to the band. What they’ve accomplished in their first time out is an eminently listenable record of genuinely fun tracks and melodies that stick, which is an achievement no matter how you frame it. For now, It’s best to just enjoy the vibes, with hope that the next album adds more singularity to the band’s limited but interesting commencement.

Writer: Andrew Bosma Section: Obscure Object

Comments are closed.