#14. To talk about C.W. Winter and Anders Edström’s The Works and Days (of Tayoko Shiojiri in the Shiotani Basin) is to talk about its basic qualities: The film is eight hours long — as if to resemble the average work day — and is derived from 27 weeks’ worth of shooting taken across 14 months, depicting a village of 47 people in Japan over five seasons, briskly paced for something this gargantuan, with the average shot said to last roughly 18 seconds. And over the film’s runtime, it maintains a steady, metronomic rhythm, observing the life of Tayoko Shiojiri as she tills the surrounding land and tends to her ailing husband Junji. Near the film’s end, during his funeral, we hear: “Junji’s life was about jazz and drinks,” as if to provide a neat summation of his existence. And similarly elemental descriptions could be said of anyone when they die. But the reality is that life cannot be fully represented through any medium, and so The Works and Days honors such impossibility through an approach to filmmaking that doubles as an avant-garde treatise.

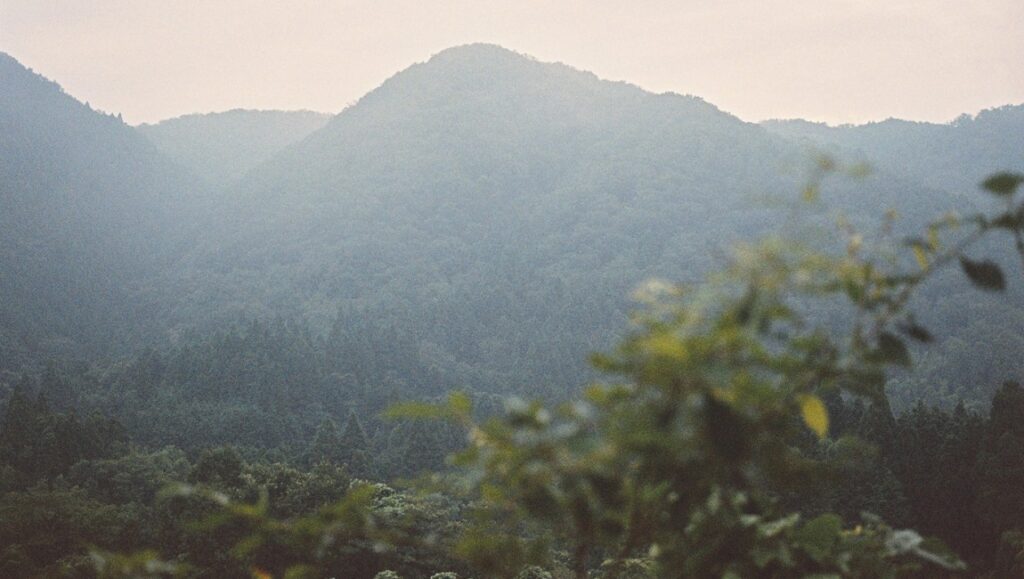

Of course, to represent “life” is a slippery ordeal, because it never exists as an isolated person or event. Winter and Edström understand that, so they create — in their lived-in filmmaking process — a work that isn’t exactly the community portrait in the manner of, say, Frederick Wiseman or Noriaki Tsuchimoto; the numerous, patient depictions of personless locales disrupt that notion. Moreover, extended passages of people musing on life never allow the trees or fields to take as immense a hold as they would in a typical landscape film. Death is seen as both undramatic conclusion and the culmination of histories, and everything is partly understood via stories and conversations, the people and spirit of a space, the way light hits and transforms a hill, the moods and memories that define beauties and regrets, the labor inherent to survival and how it stretches back countless generations. There are passages that decouple image from sound, as if to reset our methods of hearing and looking, to encourage audiences from settling into the delusion of comprehension. The Works and Days’ greatest feat, then, is in bringing us closer to understanding nothing less than life — both in the micro of what’s actually depicted, and in the macro of existence writ large — through an instructive embrace of unknowability.

Comments are closed.