French-Senegalese filmmaker Alain Gomis has been working on a film about Thelonious Monk for more than a decade. Rewind and Play is not that movie. Instead, this hour-long documentary is more of a stepping stone, one that brings Gomis closer to the inimitable jazz pianist’s process. He describes Monk as an artist who explores “intermediary spaces as if truth could be found floating in between things.” You can sense precisely that in Monk’s most exhilarating works, where zigzagging rhythms and momentary silences use this feeling of transience as an unexpected fount of emotion. Even on a more traditional piece like the Straight, No Chaser recording of “I Didn’t Know About You,” Monk could deepen a jazz standard’s emotions surrounding newfound love with the slightest curve of a melody. Gomis asserts that Monk approached his life in the same way he did his art, and it’s through this unassuming film that we see an honest depiction of who Monk really was.

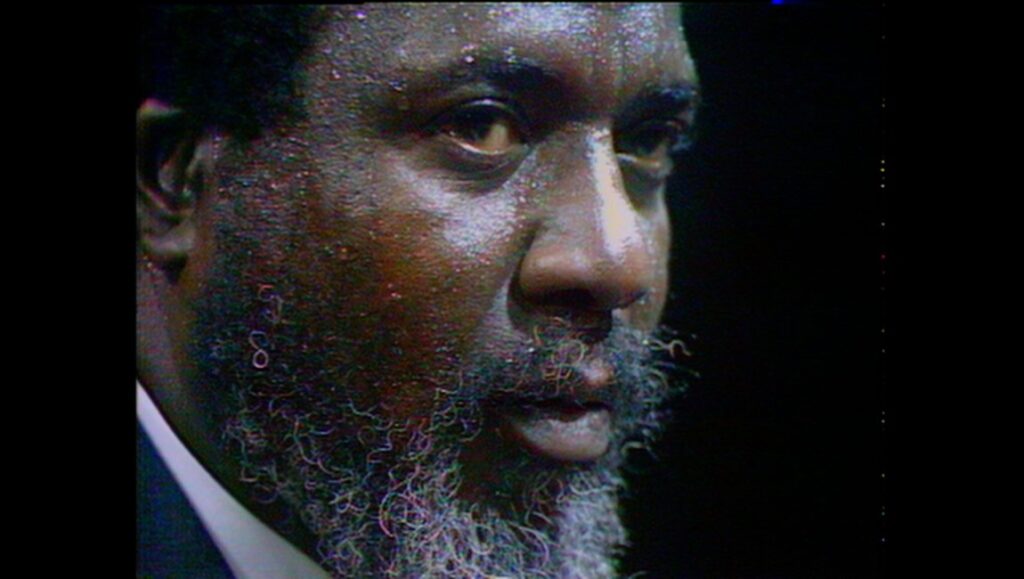

Appropriately, we don’t come to understand Monk through direct means. In 1969, he was ending his European tour with a show in Paris, but spent time earlier in the day recording a solo performance for Jazz Portrait, a French television program. This broadcast was released on DVD by Mosaic Records, touted as “Just Monk, a grand piano, and two cameras” with “no distractions.” This logline seems believable, and is of course partly true, but it wasn’t the full reality of Monk’s time there. What Gomis does is provide a necessary companion piece, editing down footage from the original two-hour film rushes to present the frustrations plaguing the proceedings.

Much of Rewind and Play revolves around the quiet tension between the interviewer — jazz musician and producer Henri Renaud — and Monk. Some of the interactions are awkward due to amateurish questioning, such as asking why Monk put his massive Baldwin grand piano in his kitchen. “That was the largest room in the apartment,” Monk replies. But Renaud continues to flail and offend in his desire to narrativize, becoming the sort of journalist who foolishly inserts personal stories because he can’t pry more details from Monk. At worst, there’s explicit racism, like when he recounts when Monk and Sonny Rollins played in Brooklyn together. At one point in the night, a fight broke out between two Black people, and Renaud likens it to something out of “the best American movies.” Such nauseating gawking mirrors the disrespect with which he treats Monk. To Renaud, Monk is merely a marketable product, and that notion is deeply felt in his constant desire to qualify the pianist’s work; he constantly repeats how this music, despite being too avant-garde for audiences in the past, is now highly respected. The work can never speak for itself.

Rewind and Play is a reminder that the media is racist because the people involved are racist. On Jazz Portrait, Monk is merely a spectacle meant to entertain, not an actual human. When Renaud asks Monk to reflect on his first concert in Paris, Monk notes that he graced the cover of a French magazine but was paid the least out of any musician in the show. Renaud chooses to ignore this injustice — a familiar experience for Monk, as he was often given paltry royalties from exploitative record labels — and scrap the take, explaining that what he said was “not nice.” As Monk is asked to repeat lines and replay pieces, the artificiality of filming this program feels increasingly at odds with the freedom found in his improvisations. What one won’t get from seeing the original broadcast is this stark contrast, and where Rewind and Play most succeeds is in revealing Monk’s absolute love for music. One of the only times we see him smile is after performing a song — in that moment, we understand how music was his ultimate form of expression, as well as a haven from everyday bullshit.

Published as part of Berlin Film Festival 2022 — Dispatch 3.

Comments are closed.