By the time of Taboo’s 1999 release, after a 13-year period of filmic silence, Nagisa Ôshima had already released what could be considered two capstone projects for the varying, protean strands of his zigzagging career. In 1983 came the English-language Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence, a WWII melodrama of startling emotion that seamlessly incorporates David Bowie into its larger aesthetic organism, retaining the sharp edges of films like Boy (1969), or even the earlier A Town of Love and Hope (1959), where external circumstances come to bear on family units, of which the band of British soldiers and their Japanese captors are comparable. Then, in 1986, came Max, Mon Amour, (in)famously the film wherein Charlotte Rampling falls in love with the eponymous chimp, catapulting the sexual liberation and/or id of something like The Pleasures of the Flesh (1965) or In the Realm of the Senses (1976) into the western sphere of bourgeoise ambassadorships and insulatedly privileged family life.

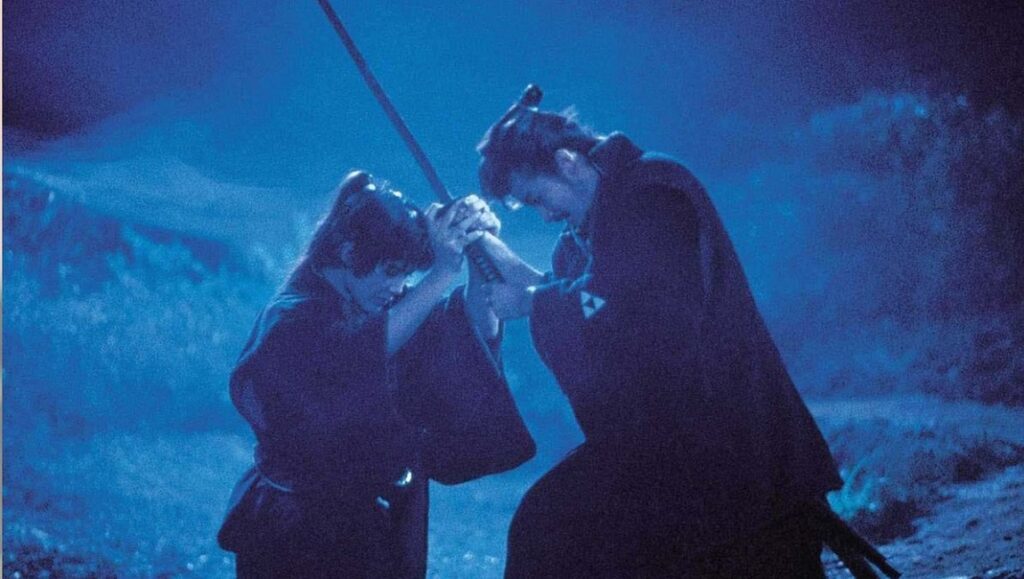

Taboo (Gohatto) is one of those anomalous final films that refuses to be categorized within any of the descriptors employed in regards to an artist’s last work: it isn’t entirely exhibiting a new temperament, yet it also ignores careerist closure; some of it is so classical that it borders on parody, and yet, its images are so charged with thwarted romance and unorthodox possibility that it’s tragic nevertheless. The final frame of Takeshi Kitano’s Vice-Commander — and samurai — Hijikata Toshizo bisecting and felling a cherry blossom tree in the cool blue of nighttime is a remarkable way to end a movie, let alone a career; however, it practically intrudes in on the film prior, cutting us off before we can get too close. As should go without saying, it’s often been affectionately dubbed as what is known as “late style.”

Similar interpersonal dynamics of films past, like The Ceremony (1971) or Sing a Song of Sex (1967), proliferate within the Kyoto Shinsengumi compound that serves as the locus of Taboo’s intrigue and casual violence. Essentially a police force conscripted to preserve the Shogunate’s often shifting feudal dictatorship, Ôshima catalogs such fascist attitudes sublimated in Hijikata’s tenure as the workaday commander who oversees training rituals, admissions, and more general, mundane activities. The Shinsengumi subtly begins to tilt off its axis upon the acceptance of the impossibly handsome Kanō Sōzaburō (Ryuhei Matsuda), whose porcelain, blemishless beauty even overshadows his superlative swordsmanship. He’s an unattainable object of affection, or at least perceived as such, because some of the men do possess him; he satisfies lust, but is also utilized as a political stepping-stool by association, and of course, considered a mere nuisance by certain higher-ups, who simply wish that their best fighter just wasn’t so sexy that he wouldn’t throw the other men into hot and bothered confusion.

There’s an obvious Pasolini connection here, Kanō being written in the mold of Terrence Stamp’s enigmatic houseguest in Teorema (1968), similarly capable of jolting a hitherto tight-knit unit out of its equilibrium with as little as an unassuming attitude paid to his own extreme beauty. And, when Kanō explains his intentions behind Shinsengumi membership — “To have the right to kill” — it rings the same as the fascist libertines’ privileged freedom for unpunished, abject brutalization in Salò, or the 120 Days of Sodom. Both Salò and Taboo are “last” films — as in Pasolini’s case, his was a career cut all too short — that dissolve the boundaries typically maintained between humor, sex, violence; these are cocktails of distilled rage and antipathy, sloshing around in a vessel of humorous formalism.

Ôshima defiantly eludes plot, no matter how much it may encroach upon Taboo’s inarguably rich conceit: Kanō is more vocal than a garden variety cipher, which is what makes the film all the more maddening as it is hypnotizing; we can’t write off all the digressions as results of some embodied blankness at the center, because the center is just autonomous enough to fulfill the scantest requirements of a protagonist. The control displayed is fierce in all its withholding and pared-back aesthetics––reliable but not flashy camerawork, Ryuichi Sakamoto’s unearthly score that’s piped in at precise times (a score, which, according to the composer, runs as something of a corrective to his overly-emotional, though still stirring, work on Merry Christmas, Mr. Lawrence) — but Taboo inevitably teeters, as if it were subject to a headrush with all the clashing desires, both political and sexual.

The filmmaker had a healthy number of period pieces in his oeuvre already, many of which were marvels of production design in how they evoked the libido of the past via their sets (In the Realm of the Senses, Empire of Passion), while also keeping a foot planted in historicity. Taboo is a few degrees removed from its predecessors, allowing for some artifice to sprout along the margins: dutch angles and the omnipresent blue of the film’s many nights. A kinship with the coming late works by Manoel de Oliveira and Raul Ruiz is suggested, where the most basic, non-realist functions of the camera are exploited to nevertheless conjure a specific past, even if it is one that is potentially misremembered. Taboo is neither an archetypal swansong, nor is it an adjacent, one-off achievement; it is a Nagisa Ôshima film.

Part of Kicking the Canon – The Film Canon.

Comments are closed.