Karmalink suffers from an inventive premise marred by uninspired execution and a lackadaisical rhythm.

Jake Wachtel’s debut feature, on paper, ticks all the boxes, and then some. A deeply personal interweaving of spirituality and science fiction, and a close-knit collaboration with cast and crew at that, Karmalink has the probable honor of being the first Cambodian work to explicitly marry its global horizons (technology, religion in a future-ready world) with its local ones (socio-economic inequality, narratives of no-name individuals) in such conceptually intriguing a premise as its title promises. Buddhist karma, roughly translated as the effects of one’s actions, is popularly invoked to justify or rationalize bad luck; in Wachtel’s futuristic vision of Phnom Penh, bad luck still exists, except that now it can not only be quantified but also digitized. But wait, there’s more: such digitization is effectively commonplace, even among the rank and file of Phnom Penh’s streets, and their paramount goal is effectively spiritual — to access the karma accrued in an individual’s past lives and therefore to facilitate one’s search for enlightenment.

This, by itself, would be enough to span a mini-series, such is its cultural intrigue and relevance in an age where religion has become increasingly commodified and, for better or worse, rendered commensurable with the hitherto alien notion of a posthuman future. Regrettably, much of this intrigue is outright squandered in Karmalink, not least due to its haphazard and ultimately inchoate attempts at world-building. Leng Heng (Leng Heng Prak), a teenage boy living in a soon-to-be-relocated neighborhood, traverses in his sleep what he claims are memories from his previous lives: first a common thief in antiquity, then a rice farmer in French Indochina, and finally a child during the U.S. bombing of Cambodia. A golden statuette of the Buddha threads through these dreams, setting forth Leng’s search for this elusive treasure along with Srey Leak (Srey Leak Chhith), a street urchin with a knack for sleuthing and scavenging for scrap gadgets to sell.

One can imagine Karmalink as a full-fledged existential noir of truly grandiose proportions, setting up its disparate narrative elements for a karmic showdown between good and evil, past and present, etc; or, as a speculative ethnography of post/transhuman society. As it stands, Wachtel doesn’t quite manage either in this bloated and clumsy stab at sci-fi. The script, courtesy of Wachtel and co-writer Christopher Larsen, gallivants between periods and places, yet feels plodding all the same, due in large part to its thinly-sketched characters and taciturn performances. Alongside Leng, Srey, and the film’s assortment of supporting characters come two neuroscientists, Vattanak (Sahajak Boonthanakit) and Sophia (Cindy Bishop), whose mysterious roles find clarification rather belatedly, nearing the film’s thematic climax and expounded in bathetic fashion.

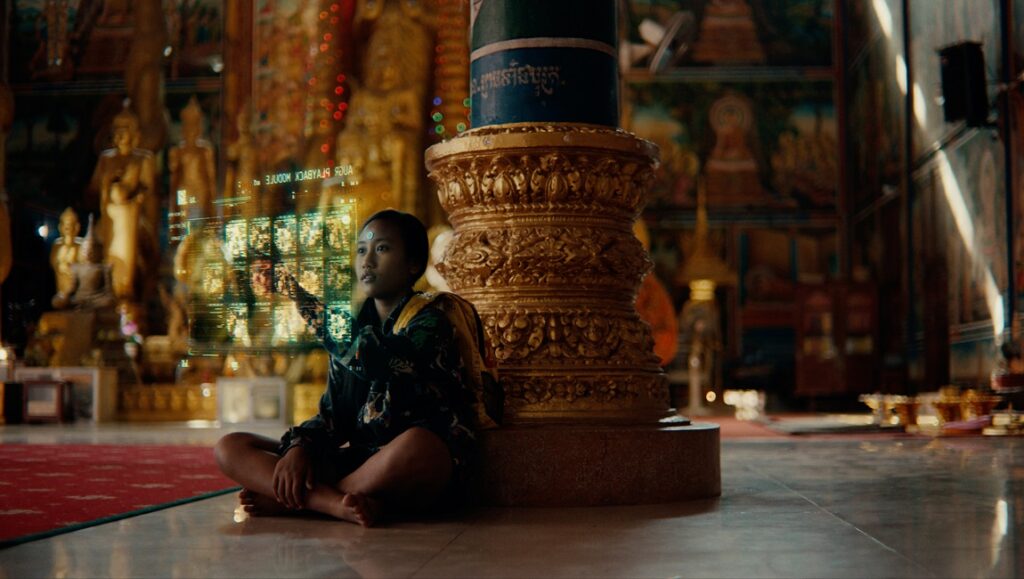

The film’s exploration of its central premise, too, will leave critical viewers wanting for more. Citizens in Karmalink’s dusty and bustling shanty towns hook themselves up to the film’s eponymous network, an augmented reality of sorts whose specific functions aren’t quite clear: is this a state-mandated implementation, designed à la corporatism or China’s social credit system for command and control purposes, or can we see in these gizmos the logical consequences of our present-day reliance on technology as therapy? A couple of key scenes — notably, the opening shot, as well as a phantasmagoric dreamscape temple in which Leng eventually meets Vattanak — are staged with formal and artistic finesse, although the large remainder feels indebted to (but never worthy of) both the tonal palettes of Blade Runner 2049 and the metaphysical ruminations present in Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s oeuvre. In sum, Karmalink suffers from an inventive premise marred by uninspired execution and a lackadaisical rhythm that, on the whole, chugs through narrative elements as if in pursuit of the cursory articulation of each. “Life after life, we are reborn,” remarks Vattanak sagely to our flummoxed youth; one wished the screenplay took itself seriously and iterated its past drafts anew.

Published as part of Before We Vanish — July 2022.

Comments are closed.