Cinephilia is necessarily littered with the detritus of half-remembered viewing experiences, films only glimpsed from childhood in a perspective almost wholly incompatible with the viewer’s current state of mind. Those two ideas overlap, a double (or triple, or quadruple, etc.) image which stirs up all sorts of memories. Sure, a viewer may have a better understanding of how the camera moves in one instant, how a particular editing pattern might seem rote where it once was thrilling, but those primordial sensations still remain; the thrill is never truly gone unless someone’s willing to make a total break.

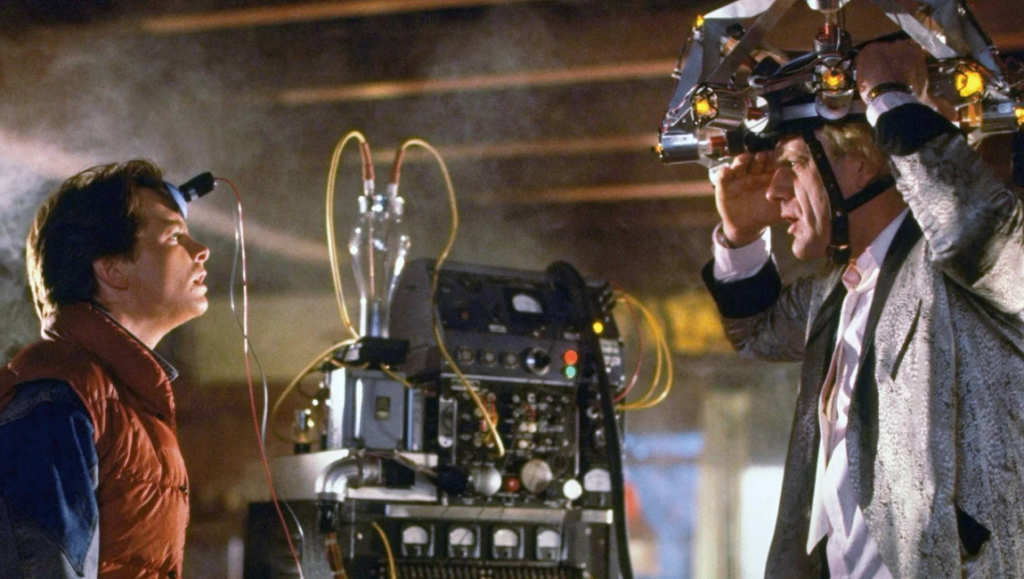

I didn’t truly become obsessed with film until the latter half of high school, but from an early age (probably until my teens) my favorite film was Back to the Future. I only had the vaguest idea of who Robert Zemeckis was; I saw Forrest Gump around this time, but the technological prowess of that film by design totally passed me by, and its qualities seemed totally divorced from the adoration I felt for the adventures of Marty McFly and Doc Brown. I was a science obsessive, a child captivated by action and popcorn filmmaking, a boy fascinated by the loop-de-loops of gags and time travel quandaries — it certainly didn’t hurt that it was one of the first films I ever saw with substantial swearing. I even had a pen with the Japanese hoverboard on it and a miniature model of the Texaco station, both from Back to the Future Part II. Even at that young age, perhaps out of that standard anti-sequel bias, I recognized that II and III weren’t quite as good as the original — one of my first memories of Rotten Tomatoes was the substantially lower approval ratings for the sequels — but I didn’t care. I became obsessed with the idea of a potential sequel almost two decades on, tracking any possible developments on the official website, and was virtually counting down the days until October 21, 2015, when flying cars and hydrated pizzas and Jaws 19 would finally come true.

In something of an effort to remain more closely tied to these rose-tinted memories, I only watched parts of the films in the trilogy, letting my mind piece together the connective tissue that links the myriad set-pieces, but even from this limited viewing, the dichotomy between the first film and its predecessors only became clearer. The original still remains one of the great works of Americana from the past forty years, a lightning bolt of summation that nevertheless manages to be an oddly small-scale film: there really are only five characters that truly matter here (Marty, Doc, Lorraine, George, and Biff), and the film takes great pleasure in constantly shuffling the tables, throwing in little bits of nonsensical gambits — the Darth Vader from the planet Vulcan scene, featuring the music of Eddie Van Halen, is a particular favorite. It’s by no means perfect: the aging makeup in 1985 is distracting, Zemeckis and screenwriter Bob Gale often get a little too cute — Marty getting to invent the skateboard chief among them — certain aspects like the random guy who tries to dance with Lorraine get to be a little too grating, and the metaphysical implications of people’s lives constantly changing based on one little interaction is too frightening to contemplate; I also have to point out that Chuck Berry released “Maybellene,” arguably even more important than “Johnny B. Goode,” well before the school dance. But it’s also just as thrilling to revisit and see the blatantly adult things (aside from the language) hiding in plain sight to a child: the blues band smoking weed, the proliferation of porno theaters in the Hill Valley town square, the relentless incestual horniness of Lorraine (more on that in a bit).

By contrast, the two sequels, while both well-constructed and engaging in their own right, shunt themselves into a bit of a corner, in doing so presaging much of modern franchise filmmaking. There’s the eerie remake of the final scene of the original in II, a sort of throwaway gag of a finale reshot with a new actress and an oh-so-subtle pause in Doc’s reaction to Marty’s worries about his future; the uncanny recasting of Crispin Glover; the back-to-back production of the sequels. Whereas the first film felt free to both swiftly create and then refer back to Hill Valley 1985, the sequels end up acting as more of a reference to the original rather than any wider idea about what it meant to live in the future, or in the Wild West. Indeed, III especially acts as a grab bag of cinematic references — none of which I knew at the time; I learned about e.g. A Fistful of Dollars through this film — irrespective of whether they belong to the Western genre or not: the playing of “My Darling Clementine” exists side-by-side with a Taxi Driver riff, though I’m pretty sure no one in Ford films (or Monument Valley generally) wore blue and pink shirts with nebulas on them.

Instead of Marty’s displacement, referring to then-Senator John F. Kennedy and Tab, not knowing how to open a bottle and getting the mocking suggestion that Jerry Lewis (one of the names that I of course didn’t know at the time) would be Vice President, there are such scenes as the Café 80s scene, recreating the skateboard/truck chase from the original yet unceremoniously crammed into the opening; I always forget that the 2015 aspect of II only takes up a third of the film. That film has the special awkwardness of having to set up entirely new signifiers and plotlines that will be directly paid off in III: the introduction of Mad Dog Tannen, the hilarious Clint Eastwood motif (considering his and Michael J. Fox’s substantial difference in stature), the random introduction of Needles, and above all the misguided attempt to have him grow via the “chicken” device. It’s not that these films don’t understand the genius of the first film: the recreation of 1955 is astonishing in its deft restaging/reshooting, helped by the quick sequel production time stalling any aging; the reintroduction of Strickland again and again is a total riot; and Christopher Lloyd and Thomas F. Wilson especially have so much fun playing their various temporal incarnations across time, though the disturbing nature of Fox playing his daughter in II and being the incredibly Irish husband to his mother’s actress in III cannot be discounted. But these crucially lack the sense of tech fetish awe afforded to even the plutonium, or the magnificent, prolonged introductions to Marty and Doc, the discovery of love echoing across time where a novel cover speaks to all the strange things that have occurred. By the end, the sentimental idea that the future ultimately isn’t written comes as a bit of a cop-out after the train barrels through the DeLorean.

Of course, the fact that Back to the Future has its anchors in the two great decades of 20th century American conservatism is a key part of its ultimately safe mainstream appeal, though the most charitable reading would suggest that the time travel acts as a sly parody/disruptor of this normalcy; the Trumpian overtones of the alternate 1985 collide oddly with a crime-ridden ‘70s vibe, though the suggestion that a second term of Reagan is so much better than a fifth term of Nixon is laughable. In purely political terms, a number of representational elements really become troubling: the cartoonish Libyan terrorists, the Black family in alternate 1985 almost shot like a horror film, the Native Americans who disappear after their magnificent entrance into the drive-thru. And of course, there is the routine usage of damsels in distress, often of a sexually violating nature. What balances them out are perhaps the two best performances in the entire series: Lea Thompson in the first and Mary Steenburgen in the third, two absolutely radiant and steadfast turns that contain so much longing appropriate to their eras: barely repressed erotic desire and timidly passionate meeting of the minds. They are the glue just as much as the beautiful friendship between Marty and Doc; just as these improbable friends maintain their compassion across centuries, so do these women carve out a slice in the timey-wimey hijinks for real emotion, which Zemeckis graciously and deftly affords them.

Back to the Future Part IV never did come to pass, perhaps for the best, but another fictional misbegotten sequel perhaps provides even more insight: Jaws 19. On the marquee, it is clearly stated that it is directed by “Max Spielberg.” Whether this was out of some fear on producer Steven’s part that he wouldn’t live to see 2015, or out of hope that his child would become a successful director (even a hack), it was yet another prediction that didn’t come true. Spielberg has improbably become a bastion of classicism — demonstrated by his actual 2015 film Bridge of Spies — but Zemeckis’ own subsequent history is left unsaid. Though he might have wanted to believe that it was as open to his own writing as it is for Marty and Jennifer at the end of III, his future was already made: the relative modesty of his first three films would be forever gone; with this quantum leap visited twice more, he barreled past the point of no return, and his reputation, for better and worse, as a technical inventor was cemented.

Part of Robert Zemeckis: Movie Magician

Comments are closed.