Please Baby Please is a gauche and grimy good time, and might wind up as 2022’s best bit of playful kink.

It’s the rare film that proves capable of achieving genuine novelty, and even rarer to find one that manages to parlay novelty alone into success. Too many such aspirants resort to gauche gimmickry or conceptually florid moonshots that result only in scaled-up failures. On its face, it might seem strange to observe this when talking about Amanda Kramer’s Please Baby Please, a film not just indebted to but intentionally cribbing from a number of aesthetic and modal reference points. But if every story tells a story that has already been told, it follows that recreation is creation. Given the thematic and discursive well it’s drawing from, it’s not surprising that at the core of the film’s singular makeup is a profound sense of the familiar, but in taking pains to defamiliarize these recognizable parts before carefully recomposing them, Please Baby Please proves to be like few other films you’re likely to have seen.

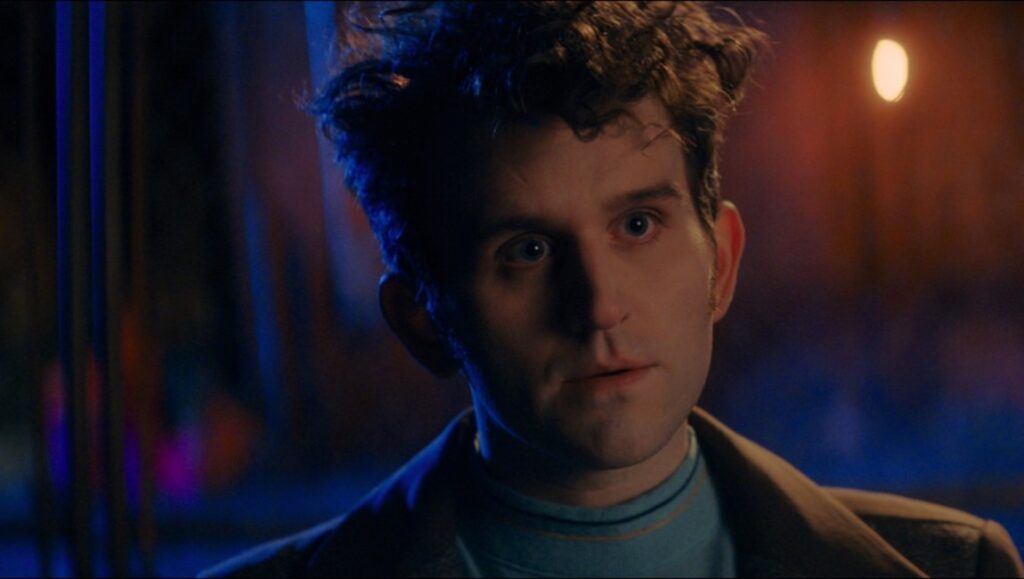

It’s a logical and liberating approach. After all, queer film — a tradition within which Kramer quite unabashedly situates her film — has long reconfigured the existing modes and traditions of the medium’s hetero homogeneity. Telegraphing her intent to do exactly this from the film’s first moments, Please Baby Please opens with a scene lifted from classical musicals of yesteryear: a roving group of leather-clad (semi-)youths, ostensibly led by Teddy (Karl Glusman) and ironically dubbed the Young Gents, dance their way down an alleyway. But any illusion of soft musical edges is immediately upset when the gang viciously murders a passerby couple for no apparent reason. Witness to the assault are Suze (Andrea Riseborough) and Arthur (Harry Melling), a newlywed couple we are soon told have heretofore shared a happy union, but who in this moment find all relationship stability obliterated. He is drawn to Teddy, their eyes meeting and lingering, Arthur struck dumb in the aftermath of this traumatizing assault, but his face and mien in this moment articulating plenty. She finds her terror quickly spun into erotic charge, stirred by the violence, the placidity of her life now thrillingly unmoored. RIP the ‘50s facade of domestic bliss.

From this moment, Arthur and Suze proceed to barrel down divergent paths, both of which are a reaction to the pervasiveness and toxicity of postwar American masculinity. He lashes out against these expectations — “I will not be terrorized into acting like a savage just because I was born male,” he asserts — and begins processing his latent homosexuality via his obsession, and increasingly tender relationship, with Teddy. Suze, meanwhile, rages against the regressive imposed order of womanhood and wifehood, especially after a run-in with vampy upstairs neighbor Maureen (a wonderfully dialed-in Demi Moore) who spouts off such delicious camp as “I ought to be famous but I’m just married.” Maureen represents a different kind of kept woman to Suze, and the liminal psychological space Suze finds herself in across the film’s remaining runtime melds her newfound fixation on violence with impressions of domesticity, realized in a series of musical fantasy sequences wherein she is given the BDSM treatment by the Young Gents while occupying traditional homemaker spaces. Through it all, Arthur and Suze take stock of their developing disengagement, often with lines as cutting as they are affected: “You know I love you. That’s implied,” Arthur notes at one point, before adding: “I love you for now. But I’m getting real nervous about the you that’s coming.”

All of this speaks to another prevailing influence on Please Baby Please: the theater, both formally and thematically. Of course, much of the narrative content here immediately recalls the modern American dramatists of mid-century America — A Streetcar Named Desire is even instructively mentioned in only the film’s second scene — an indictment and dissection of the art that for so long shaped our cultural understanding of gender roles. And much of the action here consists of monologuing and dialoguing in apartments, clubs, and other minimally furnished settings, the film’s production design quite obviously taking inspiration from a theatrical ethos. But where other films of such character too often feel divorced from the film medium, cut through by limiting dissonance, Please Baby Please leverages this quality to accentuate its sense of intimacy, Kramer guiding this influence to its most logical and pleasantly indulgent and campy ends. Riseborough, for instance, is simply ferocious, a wild performance of exquisite melodrama, something of a female counterpoint to the blustering males of the angry young men tradition (Melling is given less overt “acting” to do, though the haunted, enigmatic persona he has perfected in recent years is a tidy fit here). And in addition to the film’s more thematically scrutable colloquies, it’s also liberally peppered with all manner of hilariously baroque phrasings: “You got smog in your nog” is undeniably top-notch work; and later, riffing on the established bad boy character arc of these kinds of films, one character remarks, “That’s what a girl does. She makes a pretty poodle out of a salty dog.”

Kramer continues to fold influences into her highly aestheticized world beyond mere period/cinematic iconography. There’s more than a dash of John Waters here, and the film’s hat-tip to Kenneth Anger comes immediately and consistently throughout. But there are others reflected here, too. Peter Greenaway’s penchant for mixing the beautiful and repellent on screen, as well as for blurring art and artifice, and the boundaries of medium, are certainly woven into Please Baby Please’s essential fabric, and there’s also something of Gaspar Noe’s oversaturated scuzziness present as well (though absent his brutal explicitness and wild compositional theatrics). And Kramer punctuates all of this via the film’s visual palette: its pared-down physical spaces are bathed and appointed in blues and red, an obvious signifier of the film’s gender dichotomy but one that lends a phantasmagoric texture, dreams and nightmares spun into bold, cogent visual expression. Of course, as is the case with all camp — invoked in the least reductive way possible here — this is firmly fixed in a YMMV lane, little-to-no subtlety at hand in the text or form, all of which feels double-underlined in red. But rather than merely trading in hollow spectacle and cheap buzzword-baiting, Please Baby Please is a thesis of style. For those who often find films “in good taste” to be a bad time and who are bored to tears by the tedium of serious cinema’s self-conscious restraint, Kramer’s film might just be 2022’s best bit of kink.

Originally published as part of Fantasia Film Festival 2022 — Dispatch 6.

Comments are closed.