Falun Gong deserves a more rigorous and sophisticated defense than the templated, trend-chasing Eternal Spring is able to mount for it.

For a film with such a forceful and felt political message, Eternal Spring could have gone into much more depth about the politics surrounding the persecution of Falun Gong. Director Jason Loftus opts neither to detail the internal processes of then- PRC president and CCP general secretary Jiang Zemin’s government, when it moved to ban Falun Gong in 1999, nor to address the various stigmatizations that the media — both inside and outside China — have used to discredit the movement, resulting in a tone that comes off like pure, unabashed propaganda.

The sad thing is that the one-sided account this film gives of an unprovoked genocide perpetrated (and continued today) by the CCP is largely true — it just requires additional context to really believe and understand. For instance, it would be beneficial to know how weak Jiang Zemin’s base of power was at the time of his unexpected ascendency to general secretary as a compromise candidate after the 1989 Tiananmen massacre (an uncommonly huge promotion from his previous position as Shanghai Party secretary), and how Jiang saw the growing scale of Falun Gong as an excuse to create and exercise a military authority modeled on that which effectively crushed the Tiananmen protests a decade earlier. Similarly, Loftus could have referenced the many articles published by official Chinese media before Jiang’s 1999 ban, which lavished praise on the health and spiritual benefits of practicing Falun Gong, and even referenced testimonials from high-ranking Party officials. Lastly, the point this film is making might have been considerably more credible had Loftus acknowledged some of the criticism Falun Gong has received — whether that means addressing the “cult”-like rhetoric of some practitioners or getting into the motivations behind their staunch, very public anti-CCP stance.

On the other hand, one could argue there’s a certain justice in the approach here: Just as State-run media under Jiang launched a campaign to aggressively slander Falun Gong in the broadest and most unsubstantiated of terms, Eternal Spring leads with the uncomplicated message that “Falun Gong is good,” and produces its own counter-propaganda that’s probably coercive enough to reach the minds of some who need that kind of forced reprogramming. Unfortunately, a justified approach is not the same as a cinematically compelling one, and even taken as a blatant message-movie, Eternal Spring doesn’t really hold together: Loftus chases the prestige trail of last year’s Flee, in choosing to make large portions of his documentary animated reenactments of fraught memories, but even that decision feels tangential, since the comic book artist whose involvement motivates it isn’t directly related to the main narrative.

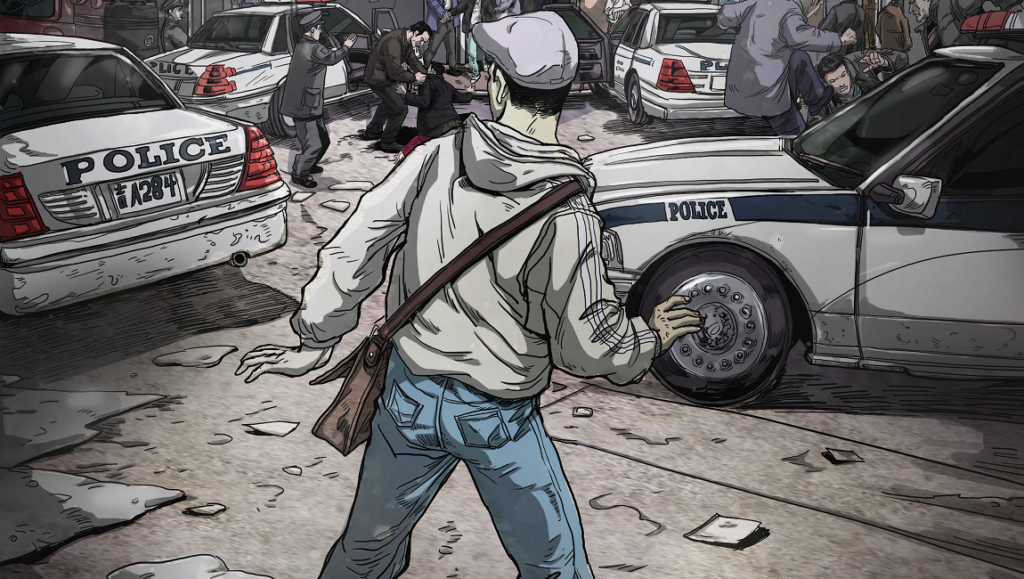

The various 3D animation sequences in Eternal Spring — like the opening action set-piece, which depicts Falun Gong activists who were responsible for staging a highly risky 2002 hijacking of State TV being methodically tracked down and arrested by Chinese police — were influenced by storyboards and character designs drawn by Daxiong, a famous comic book artist for DC and Dark Horse, who also happens to be a practitioner of Falun Gong. Daxiong was not a part of the TV hijacking, though he did live in the same city in which it took place (Changchun, in the northeast of China), and he becomes a kind of guide for this film, as he travels to interview some of the people (notably a “Mr. White” in South Korea) who managed to flee China after lengthy periods of incarceration. Most of Eternal Spring unfolds like a heist film; on-screen text labels the various hijackers things like “The Electrician” and “The Mastermind.” Loftus tries to validate this genre-fication with Daxiong’s narration, as he draws comparisons between the “heroes” of the hijacking and mythic warriors of the classical Chinese comics he read as a child.

There are two main problems with Eternal Spring. The first is that there isn’t much thought or attention given to what Falun Gong actually is (aside from a better-marketed form of qigong, thanks to charismatic founder Li Hongzhi), and so a lack of understanding as to why people would die for it. The second problem is that the hijacking itself doesn’t seem particularly momentous – in practical terms, a group of people who were either jailed for years or died of the conditions that they were subjected to inside Chinese prisons sacrificed themselves for 10 to 50 minutes of broadcast time (there are varying reports on the duration) that clearly failed to move the needle on public opinion of Falun Gong in China. In any case, there’s a much bigger, and more persuasive, story to tell about the persecution of Falun Gong by the CCP, such that even though Eternal Spring manages a few affecting movements by dialing into these specific recollections of oppression (and of people who died fighting), it fails to grapple with broader political implications. (For instance, how the labor camps for Falun Gong practitioners could be seen as a blueprint for the Uighur re-education camps the CCP has set-up in Xinjiang today.)

Ultimately, Eternal Spring suffers from the same kind of poor management of its messaging and its media that’s caused so many to believe the fabricated narrative the CCP put forth. Whole scenes unfold with the gait of storybook fiction, which is exactly the kind of distance you don’t want to put between viewers and these events (and compounds the effect already created by the emotionally inexpressive animation). Falun Gong deserves a more rigorous and sophisticated defense than this templated, trend-chasing documentary is able to mount for it.

Published as part of Before We Vanish — October 2022.

Comments are closed.