Corridors of Power is rooted in ideological ambivalence and provides a platform for imperialist voices to design history around their perspective.

Israeli documentary filmmaker Dror Moreh, whose lens oft focuses on the state interplay of power, specifically regarding the affairs of occupation, here turns his gaze onto the world stage, a stage anew, brought about by the collapse of the Soviet Union. The Corridors of Power is an expositional investigation into, as was the case in previous effort The Gatekeepers (2012), the moral reflexivity of those individuals involved in the construction of imperial power, though Moreh treads carefully (and perhaps ignorantly) as to not call this spade a spade. We sit down with a collection of highly-ranked US officials, each engulfed in world affairs across the last three decades. We are guided through anecdotal recollection of the Bosnian War, the Rwandan Genocide, the Somali Civil War (very briefly), the Kosovo War, the Iraq invasion, Obama’s Nobel Peace Prize speech, the Arab Spring — specifically centering on the Second Libyan Civil War and corollary NATO invasion — and, finally, the Syrian civil war.

Moreh sits down with a collection of who’s who to, and this must be understood, neither challenge nor confront, but glean. We glean from the likes of Madeleine Albright (former Secretary of State), James Baker (former Secretary of State), George Shultz (former Secretary of State), Condoleezza Rice (former Secretary of State), Leon Panetta (former Secretary of State and Director of the CIA), and a collection of others ranging from former National Security Advisors to Chiefs of Staff to the former National Coordinator for Security and Counter-terrorism. And if this wasn’t enough, war criminals Colin Powell, Henry Kissinger, and Hillary Clinton get a chair, too; Kissinger is only present in the beginning, and not for more than a handful of seconds, leading one to wonder what exactly was said during the course of his interview that would be cause for his subsequent absence, while Clinton comes in only after Iraq has been moved on from, offering her perspective on Gaddafi and remaining to insist on the needed intervention, which would lead to the current state of active slave trades and perpetual civil unrest under an infrastructure destroyed by the west (NATO), leaving civilians with no resources or economic capacity. Moreh gives each of these unruly imperialists plenty of time to shape their narrative, pushing back only once on screen, to Powell, who immediately shuts him down.

But the problems with Corridors goes well beyond its brazen platforming. What we have here is a film that’s conceit lies in ideological ambivalence, which conclusively allows those with very determined imperial goals to design history around their perspective. In so many words, what Moreh sits down with and allows to speak because of his centrist curiosities is an essentialist and supremacist warmonger, whose lies crystallize into the material that our understanding of history becomes made up of. Of course, that’s only if you don’t do the research yourself — something that takes less time than the runtime of this film to accomplish, wherein one can easily uncover a plethora of resources, printed even by Western-sympathetic sources such as the Guardian, in which the narratives this film allows to be parroted are broken down, demystified, and given proper context. Take as one example the film’s overview of the Kosovo war, wherein NATO acts unilaterally to bomb the Yugoslavian army, which, in fact, lead to more civilian deaths than military — in the Guardian, May 18th, 1999, it’s written:

“The media impression of a series of NATO ‘blunders’ is false. Anyone scrutinizing the unpublished list of targets hit by NATO is left in little doubt that a deliberate terror campaign is being waged against the civilian population of Yugoslavia. Eighteen hospitals and clinics and at least 200 nurseries, schools, colleges and students’ dormitories have been destroyed or damaged together with housing estates, hotels, libraries, youth centres, theatres, museums, churches and 14th-century monasteries on the World Heritage list. Farms have been bombed, their crops set on fire […] Every day, three times more civilians are killed by NATO than the daily estimate of deaths of Kosovans in the months prior to the bombing.”

This intervention was triggered by Clinton after the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia refused to sign the Rambouillet accords. These accords, as reported in the New Statesmen on May 17th, 1999, states:

“…a NATO force occupying Kosovo must have complete and unaccountable political power, {quoting the accords now} ‘immune from all legal process, whether civil, administrative or criminal, [and] under all circumstances and at all times, immune from [all laws] governing any criminal or disciplinary offences which may be committed by NATO personnel in the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia… NATO personnel shall enjoy… with their vehicles, vessel, aircraft and equipment, free and unrestricted passage and unimpeded access throughout the Federal Republic of Yugoslavia, including associated airspace and territorial waters.’”

Here, NATO asks Yugoslavia to sign over their occupation, and if they don’t, face shelling which would end up killing approximately 2500 civilians. That Moreh cannot conceive of confronting these American imperialists and their warped narrative with information very easily and immediately accessible, nor offer such intervention within the edit, is unconscionable. Though, frankly, it’s also to be expected.

In his Director’s Notes, Moreh says the following:

“The result is a nerve-racking life-and-death drama involving thousands of people, and upon which the future of entire nations often depended. It is also the story of personal rivalries, shifting allegiances and conflicting world views, featuring the very people behind the decisions. Interviews with some participant salready reveal that they agonize over the decisions they took: did I make the right call? Could I have done it differently? Did I make the world a better place?”

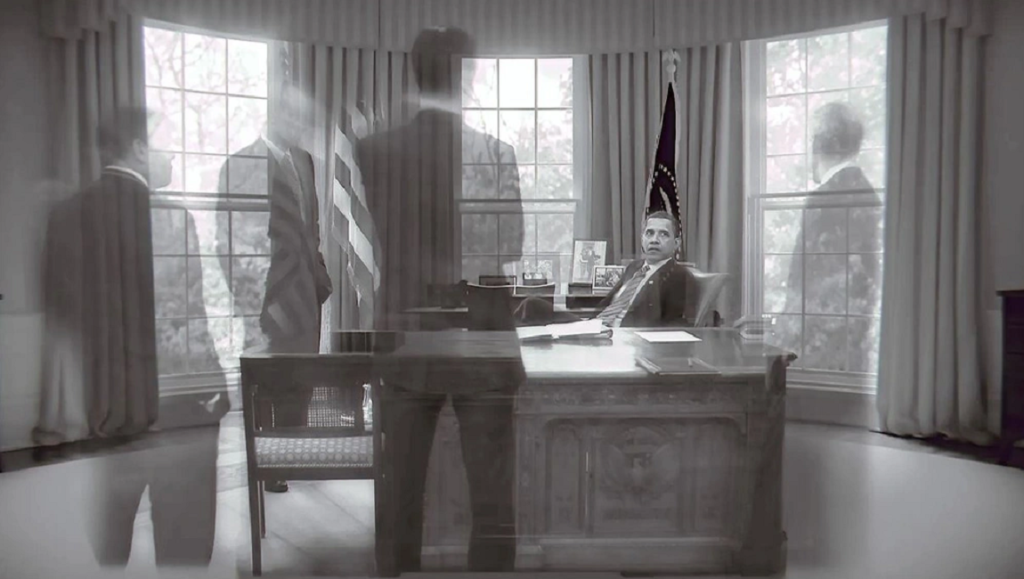

His only concern seems to be that of personal moralism, offering platform to voice regret, assurance, reflection — all while using the history and images of death and decay in the global South as aestheticized backdrop and provocation. He will linger on images of dead Syrian children, of deformed Tutsi corpses, on Bosnians running for their life, always cutting back to the American, sitting straight in their chair and justifying themselves. The suffering is dehumanized, is made a prop in service of these utterly objectifying gazes and reductive contextualizations: gawking at genocide, leering at murder, giving the only voice to those most responsible for the turmoil across the globe. Vague chapter headings such as INTEREST or IDEALS or RESPONSIBILITY haphazardly seek to form some philosophical structure around this continuity, but the overarching frame this film tempts is that of American guilt: Clinton’s guilt in not intervening in Rwanda leading to Bosnia and Kosovo, Obama’s woe at the sight of civil unrest pretext for narrowly arbitrating in Syria. Moreh sees an opportunity to psychoanalyze the American Superpower, and while that idea is fine enough in a bubble of abstraction, when brought forth into the world it only reeks of passivity and a reaffirmation of hegemony.

The final minutes of the film offers two ludicrous sentiments that strongly, if not wholly, insist on the work’s total lack of cogency: 1) In a voiceover during the last seconds, which sounds oddly like George Clooney, over an image of the UN General Assembly Hall, we hear: “We were brought up to believe that the UN was formed to ensure that the Holocaust could never happen again. This genocide will be on your watch. How you deal with it will be your legacy. Your Rwanda. Your Cambodia. Your Auschwitz.” Ironically, and cruelly so, we remember that the film opens with Kissinger. Further, this is a thread that is weaved throughout the film. The Holocaust is an image persistently evoked as to justify intervention, by these politicians but also the filmmaker. Naturally, the failure to reconcile with the material conditions of WWII in contest with the absolutely gobsmacking list of interventionist campaigns wrought by the USA — it’s an irresponsible and grossly miscalculated conflation that further feeds into the desecrating infrastructure that we know as the Holocaust Industry. And 2) Jake Sullivan, former Director of Policy Planning and former National Security Advisor to the current President has this to say: “I believe that the United States bears responsibility to try to rally action in response to genocide, mass killings, mass atrocities, so that the world does not descend into a darkness and madness. We have an obligation to play a central role, but not a singular role.” This is a meagre extension of condescending, supremacist perspective, wherein the world’s ethical and political compass is attuned to the USA as north star. This is the very lie that fed into the realization of the Batista regime, the Pinochet regime, Saddam Husain’s reign, the Taliban, ISIS, Castelo Branco, Carlos Castillo Armas, Syngman Rhee, and so many more. Sullivan believes that the USA, in their processes of intervention, which essentially culminates into the backing of these men, ensured that darkness and madness did not descend upon the world. And here we are left wondering, what the absolute fuck is he talking about?

Comments are closed.