Bill Forsyth may have to bear the reductive, buzzy distinction of having “put Scottish cinema on the map,” but he at least did so with both a disarming degree of separation — shifting the sensation of discovery onto his characters — and an expectedly warm familiarity. Originally an aspiring writer, Forsyth prioritizes novelistic detail over momentum, which allows him to poke fun at his country while also reveling in its low-key uniqueness, juggling breaks in perspective like they were the most graceful of chapter or paragraph breaks.

Local Hero (1983), only Forsyth’s third feature film, is a crystallized, just barely diaphanous collection of his gestural strengths, the narrative hitting pockets of great poignancy and astuteness, its ambling gait unlocking the significance of all the circumstantial happenstance (that’s daubed upon the narrative) as respective grace notes. With a subtle environmentalism undergirding the film, Forsyth renders human relationships inextricable from the natural world: A Texas oil man, MacIntyre (Peter Riegert), is sent off to the fictional coastal town of Ferness, Scotland, by his batty, star-gazing boss, Felix Happer (Burt Lancaster), to convince the local populace to allow their land to be purchased and repurposed as a refinery. MacIntyre expects to meet resistance, but the townspeople actually welcome the chance of being bought out, the first of many Forsyth subversions. With figures as high as they are, Forsyth doesn’t pretend that there wouldn’t be at least some enticement, thus embarking on a journey of discovery rather than a standard us-vs.-them standoff.

The beauty of the landscape — wonderfully captured and preserved by cinematographer Chris Menges — throws Mac, as well as his Scottish associate, Danny Oldsen (Peter Capaldi), into something of a comfy tizzy, tendrils of relaxation working their way over the two, as Mac goes wading through tide pools as his beard grows out, and Danny romantically communes with a selkie-scientist, Marina (Jenny Seagrove). The jokes are loosely strung together, relying on a repetition that’s atomized across scenes, rather than actual delivery, and this method of snowballing humor makes Forsyth a modest heir to Preston Sturges (which is even more visible in his follow-up, 1984’s Comfort and Joy), with the comedy leveling the playing field for all the players; there are some ripostes and whatnot, but this isn’t exactly a movie where characters score off one another.

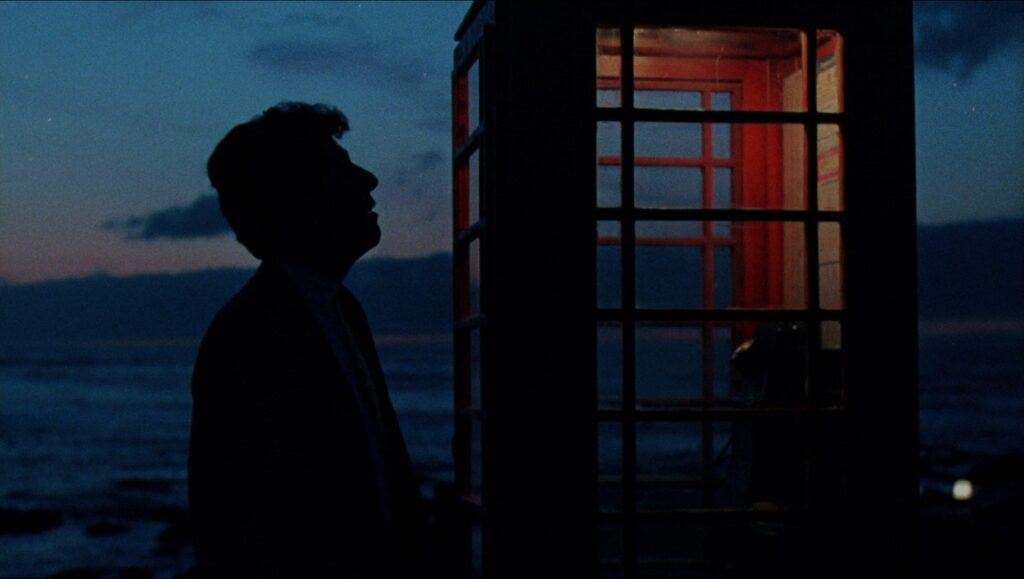

Lancaster, for his part, handles the broader comedic strokes, while Riegert trades straight-man duties with Dennis Lawson, who, as Gordon Urquhart, is Ferness’ financial advisor, hotel proprietor, bartender, soothsayer, and more. The dynamic between these two men — a friendship borne from what was anticipated to be a more fractious professional exchange — speaks to Local Hero’s simple, yet fleeting, pleasures, an almost random union between two men that exudes a self-effacing, puzzle-piece perfection. In fact, the majority of the relationships in Local Hero, in their finiteness, foresee modern globalization; Mac was dispatched with money on the mind, but the isolation — communication with the States achievable only by faulty payphone — effectively ensconced him. It’s not a fantasy about being unreachable, because reachability wasn’t as all-pervasive then as it is now, but rather proof of the tangible possibility of inner change, free from influence of all kinds.

Part of Kicking the Canon — The Film Canon.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 7.

Comments are closed.