The new feature from Naomi Uman is a three-part documentary portrait of life in the town of Rabdisht, Albania. Taking certain cues from experimental ethnographers such as Trinh T. Minh-ha and Jonas Mekas, Uman works to establish a coherent sense of place and culture, and then begins to break down those apparent certainties. Uman has been working in this nonfiction mode for quite some time, but many may remember her earlier short films, which worked with the physical material of the filmstrip in order to produce wry social commentary. Her best-known film from that period, Removed (1999), took a passage from a late-’60s/early ‘70s porno and meticulously removed the images of women using nail polish remover. The resulting film displayed aroused men canoodling with amorphous blobs of light.

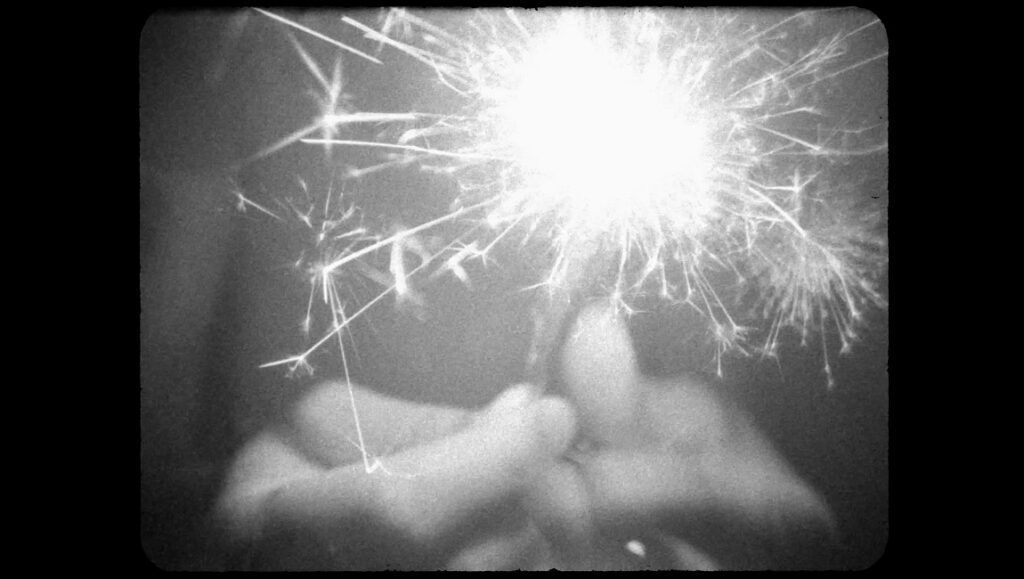

In many ways, three sparks is a somewhat more conventional film. Although the first part, shot on 16mm, displays scratches, flares, and other blemishes on the celluloid itself, we are mostly shown the everyday activities of the people of Rabdisht. Uman interrupts the movement from scene to scene with title cards that provide historical data, identify the people in the film, and generally serve to explain what it is that we’re seeing. This is a fairly straightforward denotative maneuver, one in keeping with the traditional methods of ethnographic cinema.

As the film progresses, however, Uman becomes more focused on the specific individuals in front of her camera rather than the cultural atmosphere that has, in part, produced them. (Uman repeatedly provides full-length portraits of her subjects, especially the women, starting from their faces and panning down, paying particular attention to their shoes.) The final section of three sparks shifts from film to digital video, and is much more motivated by the subjects themselves. They position the camera at odd angles to show themselves making bread or watching TV, and in one instance, a young girl throws the camera into a pile of clothes on her bedroom floor — as if casting the entire project aside.

There are a number of key concepts to which Uman repeatedly returns. One of them is the Albanian concept of besa, wherein it is the highest moral injunction to be cordial, welcoming, and neighborly. While this usually pertains to acts of everyday grace, Uman explains that it was besa that compelled both Christian and Muslim Albanians to hide their Jewish neighbors from the Nazis during the war. It also serves to explain why religious strife is rare in Albania, relative to other Eastern European nations. three sparks also discusses the concept of the “sworn virgin,” in which women take on masculine identities and are granted all the privileges of traditional Albanian patriarchy. While Uman is correct that this suggests a certain acceptance of gender fluidity, it’s clear that it only works in one direction. As we see in the anti-trans initiatives around the world, female masculinity confuses patriarchy, but male femininity is intolerable. three sparks suggests that perhaps we can learn from Albanian culture, but in some regards, we may be all too similar.

Published as part of InRO Weekly — Volume 1, Issue 18.

Comments are closed.