Los Alamos, New Mexico: Apache country. Just a half-hour drive from Santa Fe, the land of Los Alamos was sparse but beautiful. The land hosts the most diverse range of flora in the region; the otherwise endless horizon of red dirt is broken by green bushes and vibrant flowers, which itself is broken by the steep mesas that form the rural New Mexico skyline which graces the public imagination through gorgeous mid-century postcards and Western movies. Those Westerns promise that this land was a violent one and that the Apache people, using these mesas as citadel walls, uniquely deserved their violent fate as, according to these movies, they started it. Other films, like Ride the Pink Horse (1947), Hang ‘Em High (1969), or No Country for Old Men (2007), also use violence as a defining feature of this desert, usually as a method of settling scores and balancing sins. After the U.S. Department of War declared eminent domain over this place, they built the ramshackle city of the Manhattan Project on the same natural citadels the Apaches used centuries earlier — for protection and for privacy. They were there to balance sins by wiping the slate clean.

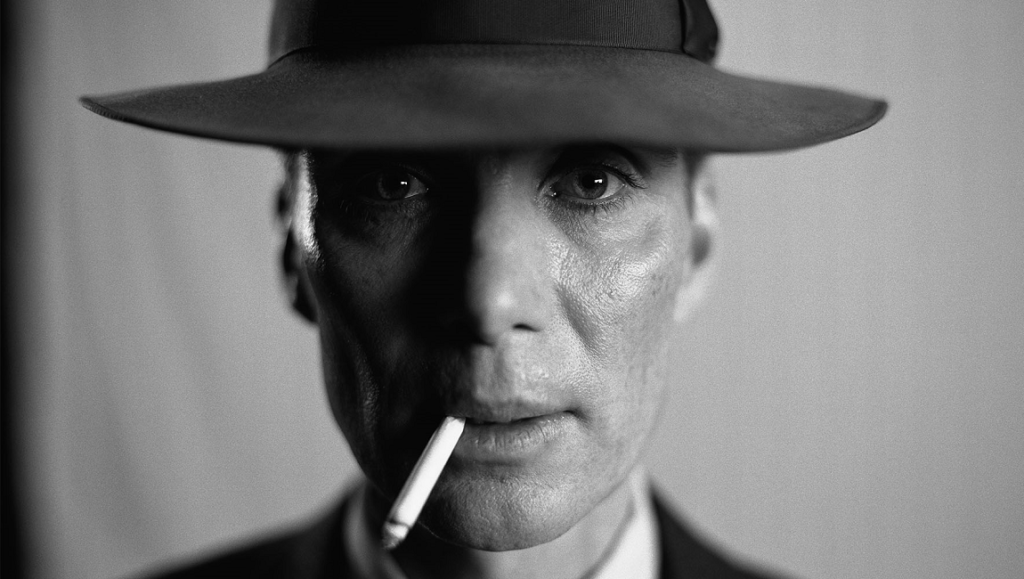

Christopher Nolan, perhaps in a flippant mood, described his newest Oppenheimer as a Western, and, in the sense that violence is meted out in a lawless world, it can be. But, unlike a John Ford picture, there are no shots placing the tiny figures in the context of the desert vista; unlike Howard Hawks’ work, there are no moments in which the gigantic cast can relax within the frame, shoot the shit, and otherwise act like a human community before the drama starts. As its title suggests, this film is very much about J. Robert Oppenheimer (Cillian Murphy) himself; so his gaunt, sunken face takes center stage, and the land, the houses, other people, all the factors that may influence the “most important man who’s ever lived,” fall into the IMAX camera’s shallow focus. The real Oppenheimer was a product of his environment: he took great interest in the education that was afforded him, learning about contemporary art, philosophy, poetry, literature, history, and living a life of the mind before settling on the scientific version of head-in-the-clouds curiosity that was theoretical physics. He was brought into politics thanks to living in the most politically interesting time in centuries — perhaps ever — and he loved his bit of land in New Mexico. And his legacy of building the bomb only to rabidly denounce future bombs was as much a byproduct of government bureaucracy and wartime determinism as it was the big choices of an important man. In Nolan’s film, these are worth mentioning, perhaps in a list, only to fade into the glassy miasmatic blur around Murphy’s visage avec cigarette.

Oppenheimer‘s narrative is framed by two “trials:” the titular character’s security clearance review and the Congressional hearings for Lewis Strauss’ (Robert Downey Jr.) Cabinet nomination. Nearly half the movie takes place in these rooms as Oppenheimer’s character and political leanings are questioned, contested, and defended, allowing Nolan to frame and contextualize each scene or additional character. Flashbacks form the half that isn’t a political thriller, as a college-aged Oppenheimer meets the most famous physicists who ever lived, only to become a star himself at UC Berkeley. He falls for Communism and for Communist women, namely Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh), whose name will haunt Robert’s life and the prosecution’s files. But Robert, a Jewish man, recognizes the threat of Hitler as the war rages, and, after a thorough vetting process from General Groves (Matt Damon), channels his political chutzpah into beating the Nazis to nuclear fission. He rallies America’s top scientists — much to the chagrin of military snoops who see Communist Jews in any intellectual activity — into the Manhattan Project, which, headquartered in Oppenheimer’s beloved New Mexico desert, aimed to weaponize the fission process in the form of a bomb, cheerfully termed by Alamosians as “the gadget.” And there, in the land of Acme dynamite and the nation’s first revenge thrillers, they, like the Hebrews in a desert before them, summon the pillar of fire and the pillar of cloud. Nolan then, for the final hour, focuses on the two hearings and the political backstabbing that would cement Oppenheimer’s legacy.

Though this movie comes with some cinematographic pedigree and bragging rights, boasting both IMAX veteran DP Hoyte van Hoytema and the first ever black-and-white Kodak IMAX film stock, Nolan never uses IMAX for a uniquely IMAX composition. Little of the movie ever strays from Cillian Murphy’s face — even establishing shots are usually wide interior shots populated by a few people, with Murphy never far away. That said, IMAX, despite its reputation for being larger than the largest screens, has a small aspect ratio, sometimes 1.43:1, giving Nolan the opportunity to shoot this like an old Academy ratio Hollywood movie. He’s never interested in landscapes, just a body or two to pose in the frame before an inevitable reverse shot. To give Nolan too much credit, one could see a mirror to one of the best movies about faces and suffering, The Passion of Joan of Arc (1928), where Maria Falconetti’s tears and twinges can speak for themselves. This aspect ratio makes sense for Nolan’s movie, but his IMAX fetishization and an inevitable studio reluctance for conventional 1.37:1 pictures leads to the largest possible version of a rote political thriller.

But, even if one accepts that rote political thrillers usually care less about visual appeal and more about images working in favor of the story, Nolan’s script comes up dry. With no-nonsense editing, Nolan cuts from line to line as quickly as possible in order to match the speed of the actors’ performances. No single character seems to have a fleshed-out personality, so each scene devolves into characters finishing each others’ lines in order to give the audience the most information possible, or, as in the sequence where Oppenheimer first meets General Groves, each character matches the previous line with a clever riposte. Every character seems interested in competitive tête-à-têtes or simply getting to the bottom of that day’s shooting script — a result of trying to actually adapt all 700 pages of American Prometheus in three hours. Some of the most dramatic moments even opt for a cartoonish gravitas, such as Oppenheimer’s admittance that “When I was a kid, I thought if I could find a way to mix physics and New Mexico, my life would be perfect.” This bit of irony is supposed to spell out the tragedy of Oppenheimer’s career, but it does so loudly and literally. Just like Nolan’s choice to make the “objective” (whatever that means) scenes black-and-white, any potential cleverness in Oppenheimer is ruined by the sophomoric instinct to announce and explain itself.

Yet, there are flashes of curiosity and wonder, such as Andrew Jackson’s special effects work that visualizes the abstract, counterintuitive parts of quantum physics. Flashes of erupting particles melt out in one of Oppenheimer’s study sessions while vibrating waves and ripples accompany another, interrupting the more literal flow of interrogation and info-dumping that makes up most of the film. With those images come the ethereal static and sine waves from Ludwig Göransson’s soundtrack, which articulates the strangeness of these revolutionary concepts that somehow describe our world, even if we cannot picture this new world at all. Then, the bomb itself, the centerpiece of the movie, manages to evoke both the horror and beauty that all those at Trinity Site described. The flames bubble out not like the whips of a campfire, but like ink filling a tub of water, hinting at a deadly viscosity that’s tangible, edible like the mesmerizing path of a lava lamp. Nolan opts for a silence here — a welcome respite.

Then, after the two cases have been resolved and Oppenheimer’s character has been effectively muddled, the physicist gives us one last dramatic sendoff. Had the movie meditated on the bomb and its consequences, the final sequence could have elicited a frisson comparable to the best of cosmic horror. But since this movie touches on every issue of American Prometheus as fast as it can, it’s easy to forget the grander issues — the kind that a young Oppenheimer concerned himself with — in favor of the more petty squabbles of prosecutors and witnesses. The real story of Oppenheimer (as mentioned in The Day after Trinity [1981]) is the story of Faust, where power and knowledge are granted in exchange for what gives those things value. But Nolan’s Oppenheimer has no Mephistopheles; it has only Prometheus and Vishnu, who, as soon as they’re mentioned, disappear into the pool of shallow focus such that only one god remains.

DIRECTOR: Christopher Nolan; CAST: Cillian Murphy, Robert Downey Jr., Emily Blunt, Matt Damon; DISTRIBUTOR: Universal Pictures; IN THEATERS: July 21; RUNTIME: 3 hr.

Comments are closed.