Do we still need the album? That question — elicited by the advent of streaming music platforms and the musicians’ newfound ability to self-publish songs as soon as they’re finished — calls out the album as a historical object, not a permanent fixture in music culture. LPs, introduced in 1948 by Columbia Records, were initially considered to be vehicles for collections of singles, hits, or generally related music. And though they may not have been the first, the success of the Beatles introduced the world to the album as we conceive of it today, thanks to records like Revolver. Others would follow, recording songs not meant as singles, but as pieces in a concordant assembly. While this certainly helped musicians conceive of themselves as artists or storytellers, it helped the music industry even more. Now, artists’ works could be sold on the strength of the project itself — the album can be branded, marketed, and quantified outside of the artist’s most recent singles or even the artist themselves. This was especially a boon for music criticism, a job that was reinvented with the album, as each album could represent a “new direction” or “a comeback” or “an experiment” or “a failure” or “the greatest of all time,” perhaps even independent of the critic’s former opinion of the artist or the individual songs. Then, in the age of streaming, two branches appeared in this history. The first represented post-recession market logic, as demands for short-term profit to boost quarterly earnings created a supply of an endless parade of singles and music videos — why wait for an album? The second represented the artists doubling down on the concept of the album (and, therefore, their image as artists) with surprise album drops, thirty-song projects that would’ve never sold in the days of physical media, and the visual album. The latter is perhaps the most interesting, as it doubles down fully on the aesthetic logic of the album: now, music videos, once thought as television ads for singles, must themselves cohere into a single aesthetic object.

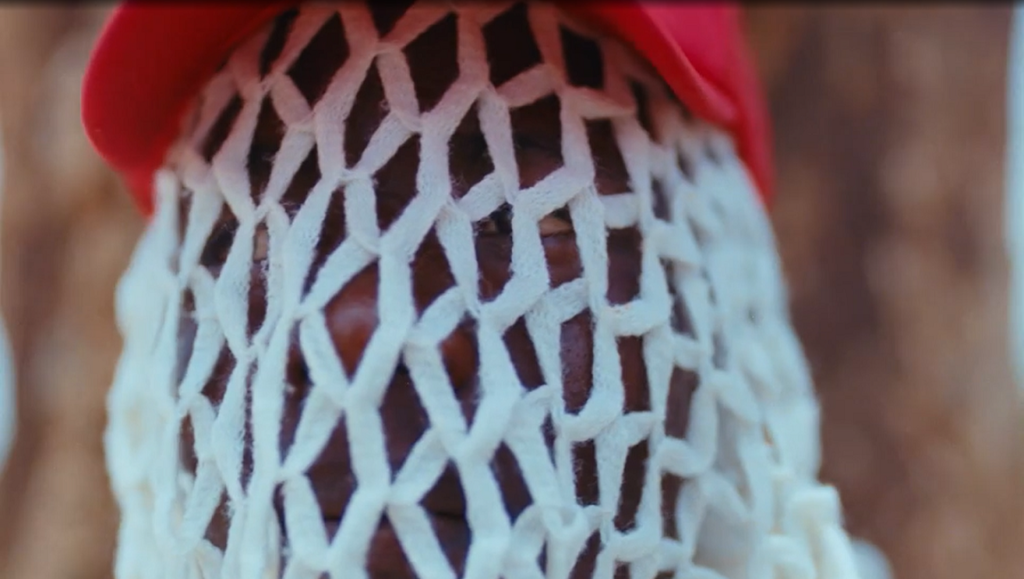

Travis Scott’s new film Circus Maximus takes full advantage of these new artistic signifiers, as it arrives as both a surprise release and a visual album. By opting for this style of release and by limiting the showings to a few days in a few theaters in a few cities, Scott also cleverly self-selects the film’s audience. Music films are always fans-only affairs — why would one watch an LCD Soundsystem concert film if they were not already an LCD Soundsystem fan? — but this method guarantees only those who actively keep up with Scott’s social media presence would buy tickets in time, subsequently guaranteeing beaming word-of-mouth marketing. It’s a smart move for an artist who’s seen nothing but negative publicity after ten people died at the Astroworld concert series celebrating the height of his fame. Though he wasn’t indicted by Texas juries, it’s difficult to imagine venues’ or fans’ continued trust in Scott’s team for the safety of his concerts. So, here is Circus Maximus, the pre-recorded concert for his new album UTOPIA, likely the only move his team could safely make.

If an album is judged according to its “albumness,” then so should a visual album be judged according to its visual consistency rather than a cumulative rating of its individual videos. Circus Maximus tries for no such thing. Instead, it’s a hastily put-together jumble of music videos, tethered by a vague overarching narrative, and a concert film; not a woven patchwork of disparate elements, but rather a product of indecision and shoddy curation. The music videos themselves are not, like Kahlil Joseph’s previous work on Beyoncé’s Lemonade (2016), representative of the album as a whole, but are mere previews of what will likely be released as singles. But, each segment is directed by a film director with cinematic bona fides (Joseph, Valdimar Jóhannsson, Gaspar Noé, Nicolas Winding Refn), giving these songs a visual heft. After Scott battles a giant squid in an Icelandic cave, we’re whisked away to a European garden where a meditative Rick Rubin asks vague questions — to which Scott gives vague answers with bravado. The next few videos travel the world (this global theme supposedly tying in to the iconography of Scott’s “UTOPIA”) as Ghanian dance, gigantic human pyramids, and Refn’s signature neon lighting whiz by. There’s a bit of humor in that Refn segment, as a masked chauffeur speeds around an empty parking lot, swerving into donuts while Scott lights another joint. There’s also a lot of fun to be had in the Noé sequence that plays like a short dance party addendum to his recent Lux Æterna (2019), with LCD walls violently flashing colors to the beat. But none of these videos quite seem interested in the others. All of this is interspersed with voyeur shots — the camera even masked to resemble the shape of an eye — with Scott and Rubin continuing to drone on in the masculine therapyspeak of something like The 48 Laws of Power.

Then, the visual album ends, and the concert film, directed by Harmony Korine, begins. Since Scott explicitly states that he’s not going to talk about “the tragedy,” this is a concert film devoid of crowds; almost devoid of anyone at all. As the sun falls, Scott walks around the center of the ruins of a Pompeian amphitheater and performs UTOPIA to a wall of speakers. Others do show up, specifically the collaborators on the album, as they also wander in, perform their verse, and wander out to the edge. Korine shoots this via a crane and a drone, meaning that it’s impossible to obfuscate the recording equipment and crew — this is clearly an aesthetic choice, but it never builds to anything more interesting than the juxtaposition of all this recording tech amongst the Romantic ruins. It plays like the first draft of an idea, though Korine throws some fun images amongst the sluggish performance, such as stone-faced cheerleaders and a robot band reminiscent of Chris Cunningham’s “Monkey Drummer” video for Aphex Twin. But Scott, known for energy, walks around without purpose, occasionally throwing a chair, like he’s doing disheartened donuts in a parking lot. Circus maximus, indeed.

That Beyoncé and Solange —both, like Scott, Houston natives — could celebrate Houston in their visual albums must sting for Scott, whose attempts to celebrate the city’s beloved Astroworld ended in tragedy, forever sullying the name. The “global” scope of this project is a way to break free of that, but there’s a fine line between universality and placeless nihilism. The result is that Circus Maximus comes across as a listless project for the sake of having a project, which may be helpful only to Scott himself. That it mostly focuses on a concert for nobody is a little too apt.

DIRECTOR: Travis Scott, Gaspar Noé, Nicolas Winding Refn, Harmony Korine, Kahlil Joseph, Valdimar Jóhannsson; CAST: Travis Scott; DISTRIBUTOR: AMC; IN THEATERS: July 27; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 16 min.

Comments are closed.