There’s a recurring motif in Cassandro where Gael García Bernal’s character, an openly gay luchador, works an outwardly hostile crowd from inside the ring; weathering the catcalls and vicious slurs that rain down upon him only to disarm the audience with his technique, flamboyant showmanship, and demonstrable joie de vivre. Strutting around in garish costumes, lounging on the turnbuckle, egging the crowd on only to then thrillingly whip his body around the ring. The character flips and contorts around opponents more than twice his size, calling into question assorted prejudices about masculinity that equate strength with size and virility. It’s an apt metaphor for the experience of watching the film itself, which courts if not hostility than healthy skepticism in its very being. Directed by documentarian Roger Ross Williams (Life, Animated) making his fiction debut, Cassandro is a feel-good sports drama — and a biopic no less — replete with training montages, heartbreaking setbacks, and defying the odds; the film was also a minor sensation at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, which is as much a blinking caution light as it is an endorsement. And yet, like its title subject, the film deftly counters one’s assumptions, ultimately winning you over with a combination of almost puppy dog enthusiasm and clear-eyed pragmatism.

García Bernal plays Saúl Armendáriz, loosely based on the real-life luchador of the same name, a Mexican-American from El Paso who crosses the border into to perform at small-time lucha libre matches. Small in stature, on the wrong side of 35, and held in open disdain by his fellow luchadors because of his sexuality — no shrinking violet, Saúl gives as good as he gets; mocked in the dressing room for his wispy mustache, he replies that he grew it because the other wrestlers like the way it tickles them — Saúl is merely an anonymous jobber: a “runt” paid to lose in order to prop up more popular luchadores. Donning the traditional luchador mask, Saúl aspires to nothing more than putting on a good show for the crowd, but his fellow wrestlers view him exclusively as a “sissy” they can quickly pin and be done with. With limited prospects for advancement, Saúl is encouraged to reinvent himself as an “exótico,” which will require him to take off the mask and place a far greater spotlight on his sexuality.

The entire concept of an exótico is a fascinating glimpse into the sexual politics of lucha libre, as well as Mexican culture more broadly. Incorporating elements of drag, including feather boas, stockings, and makeup, exóticos historically serve as foils for macho luchadores, positioning homosexuals (or simply effete men) as not merely impediments to glory in the ring, but threats to the entire notion of masculinity. Pummeling an exótico is seen as reasserting the natural order or promoting conservative Catholic values — even framing a mere exhibition as a battle between righteousness and deviancy — all while feeding into the homophobia of a crowd that screams for blood. So when Saúl, who takes his performer name “Cassandro” from a female character on a telenovela, suggests that perhaps his persona can win, it’s not simply a matter of training hard and getting lucky during a match. With outcomes determined in advance by promoters and contingent upon the fighters going along with the script, Saúl’s path to greatness hinges upon rallying a crowd conditioned to despise people who look and behave like him until they’re clamoring for his victory; indeed, the entire mercenary nature of professional wrestling is on full display when, mid-match, a ringside promoter offers a luchador double pay if he’s willing to flip the script and allow Cassandro to pin him.

Saúl is making a financial argument as much as he is a humanist one. Cassandro can be good for business either as a high-profile antagonist for more established luchadors or even the main attraction, grafting the transgression and exoticism of an exótico onto the high-flying physicality of the sport. While larger and more established luchadores may be unwilling to be pinned by an exótico, there’s only so much they can do if Cassandro is able to run circles around them in the ring, embarrassing them with his clownish antics while bringing them to their knees by employing painful arm bars and counterattacks. Once he has the crowd backing him, it’s only a question of will promoters give the people what they want?

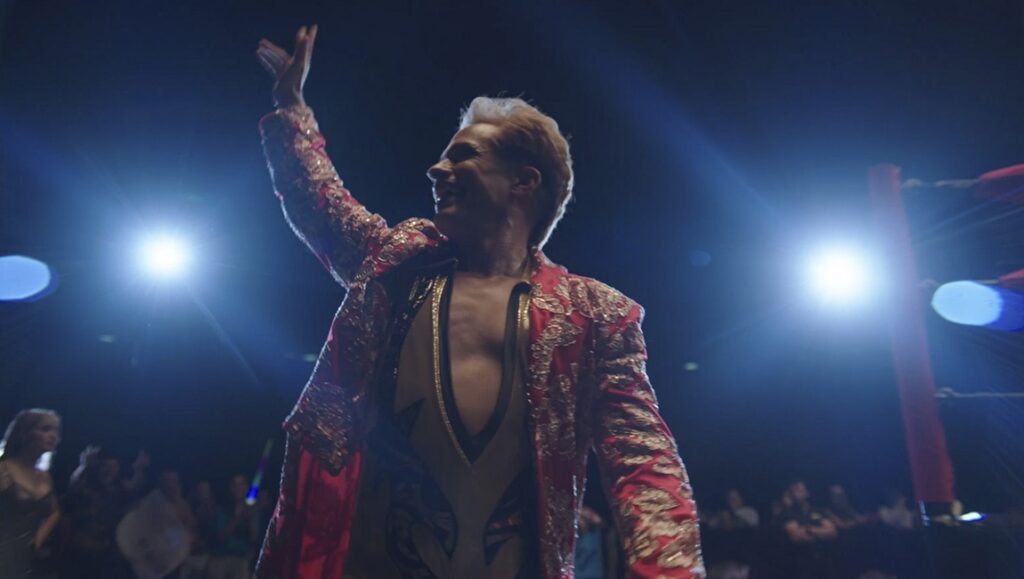

The appeal of Cassandro/Saúl is inseparable from García Bernal’s performance. Lithe and sporting prominent blonde highlights, the actor embraces Saúl’s androgyny without resorting to mincing. Strolling to the ring accompanied by Spanish-languish renditions of “I Will Survive” and “Call Me,” wearing costumes sewn from loud garments from his single mother Yocasta’s (Perla De La Rosa) wardrobe, Saúl relishes being taken for granted. The film establishes Saúl as being eager to please, doting on Yocasta (and she on him), stemming from both of them having been abandoned by Saúl’s father after he came out as a teenager. As a coping method, the character dissociates from his wrestling persona, talking about Cassandro in the third person as a more assertive, sexually confident figure than himself. “If Cassandro were here, he’d tell you many things,” Saúl sweetly says to a promoter’s handsome employee played by Bad Bunny, “that he wants to kiss you” (the scene ends unexpectedly, with neither consummation nor indignation, but rather a sort of impasse that can be interpreted as politely establishing the character is straight or perhaps a raincheck for another time). In truth, Saúl’s heart belongs to another, the closeted luchador Gerardo (Raúl Castillo) who hides his affair with Saúl from his wife and children and begins to resent Cassandro’s success. When Gerardo tells Saúl that he was happier when the latter was still an anonymous runt, Saúl clocks the situation curtly: “I was there when you wanted to fuck me and out of the way when you didn’t.”

Cassandro plays at times like a less nihilistic version of Darren Aronofsky’s The Wrestler; chronicling the toll life on the road and taking bumps has on the body, as well as acknowledging the partying, pervasive drugs, and casual sex. Like Mickey Rourke in that film, García Bernal’s performance emphasizes his physicality and athleticism, but also the intoxicating effect of the crowd and how much the character feeds off of it. After a personal tragedy leaves Saúl emotionally vulnerable during a nationally televised match against the famed luchador Son of Santos, Cassandro runs from the ring mid-match, re-emerging perched on a precarious railing several stories above the ground in a gesture that holds undeniable suicidal overtones (in reality, the actual Saúl Armendáriz did try to kill himself before the match). The scene ultimately plays out as a moment of triumph and acceptance, but it also signals a curious shift in the film’s tone. In the aftermath, we get multiple scenes of catharsis that feel at odds with the comparatively grounded film that came before, culminating in a fantastical talk show appearance that calls into question how much of what we’re seeing is meant to be taken literally (all of which is complicated by Armendáriz being an actual celebrity in Mexico to this day). It’s an unfortunate misstep, perhaps signaling Williams’ intentions of making a different kind of film than the comparatively conventional one viewers are given. But the film remains an undeniable charmer despite this blip, acknowledging the stodgy conventions of the genre while placing an electrifying, fairly singular figure at its center. There’s a kindness to Cassandro which transcends pat lessons and bromides about acceptance. The crowd cheers for Saul not because he’s cured them of their hatred, but rather because it’s hard to deny his natural charisma. The same can be said for the film.

DIRECTOR: Roger Ross Williams; CAST: Gael García Bernal, Robert Colindrez, Perla de la Rosa, Raúl Castillo; DISTRIBUTOR: Amazon Studios; IN THEATERS: September 15; STREAMING: September 22; RUNTIME: 1 hr. 47 min.

Comments are closed.