Millennium Mambo, Hou Hsiao-hsien’s 2001 romantic drama, premiered at that year’s Cannes Film Festival where it received a rather muted response, even from admirers of the Taiwanese auteur who was coming off the 1998 period film Flowers of Shanghai. In an otherwise mildly positive review for the New York Times, Elvis Mitchell said the film “feels like an episode of The O.C. directed by Wong Kar-wai” — a sentiment which reflects the contemporaneous critical tenor fairly accurately, with many seeing the effort as a failed attempt at garnering a new, younger audience. Its reputation as a minor entry into Hou’s body of work stuck around for a long time, with a 2008 Reverse Shot piece written by Chris Wisniewski bemoaning the “‘minor’ label so frequently applied to it.”

The film did, however, find an audience eventually, and looking back, it’s somewhat perplexing that Hou’s lush neon fantasia wasn’t celebrated upon release. It’s a rare film that succeeds at sinking its hooks into an audience from the very first reel: opening on a tracking shot of fluorescent lights that suggest a road tunnel, the camera glides down to reveal an illuminated overpass and a young woman, Vicky (Shu Qi), traversing its seemingly endless length in slow motion as gauzy electronica pulses in the background. Vicky’s voiceover, delivered from the then-future of 2011, looks back at her life a decade prior as she outlines her tumultuous relationship with Hao-Hao (Tuan Chun-hao). “She broke up with Hao-Hao, but he always tracked her down,” she recounts, her distance to the events emphasized by the third-person narration.

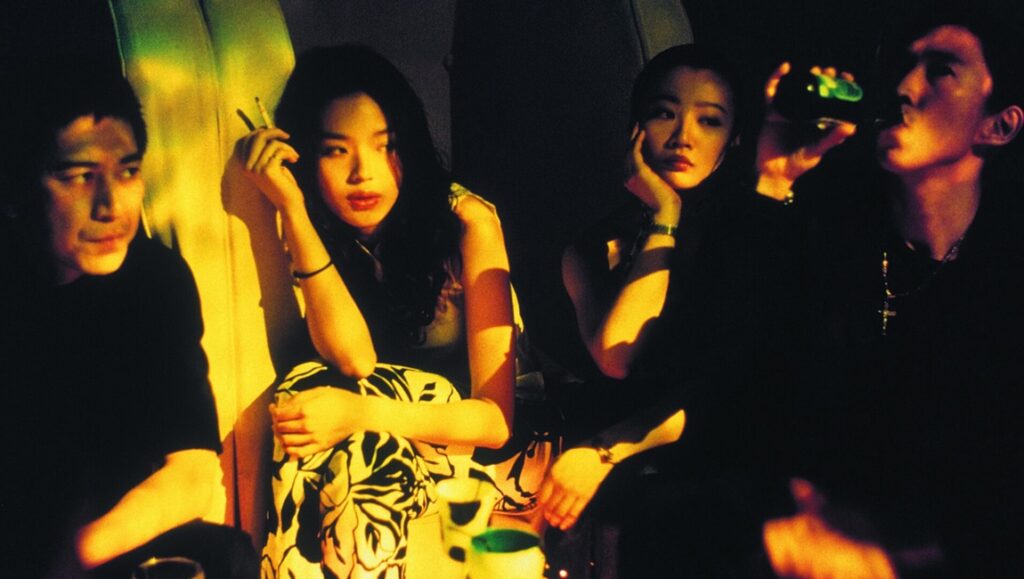

While there is a gentle narrative pull to Millennium Mambo‘s recollections of parties, relationship drama, petty crime, lovemaking, and night-time car rides, the episodes of Vicky’s life are fragmented — her narration by turn precedes, accompanies, and follows the events’ depiction onscreen, for instance — which imbues the film with an ethereal quality that is further heightened by the pervasive techno soundtrack. Vicky is like a moth to the flame when it comes to shady boyfriends and nightclubs, and Hou lets her play out these moments again and again, the elliptical storytelling suggesting an endless cycle of bad decisions. When she eventually falls in with Jack (Jack Kao), an older mobster with a more benevolent aura than the unhinged Hao-Hao, one can’t help but wonder whether or not something will cause that relationship to sour as well.

Especially to a younger audience, Vicky’s taste for that particular type of lifestyle (and man) might be understandable since Hou is more than willing to acknowledge the glamour and sensual allure it holds. But the frequent repetition also renders them exhausting and ultimately hollow, a feeble attempt at staving off the malaise that life at the end of history has saddled the characters with. Millennium Mambo plays much like a music video from the era: beautiful to look at, light on plot, and heavy on vibes — although Hou’s pop cinema wasn’t without peer. As hinted at by Mitchell, the filmmaker looked to the neon-drenched likes of Chungking Express (1994) and Fallen Angels (1995) — both directed by Wong Kar-wai — but also the lonely cityscapes of Edward Yang’s Taipei Story (1985). There are also traces of Lin Cheng-sheng’s 1997 drama Murmur of Youth, which itself took cues from Hou’s own Daughter of the Nile (1987), making for an interesting intertextual exchange between the two filmmakers.

Millennium Mambo‘s cinematographer, Mark Lee Ping-bin, who had lensed Wong’s In the Mood for Love the year before, shot the film on 35mm but deliberately gave it a soft digital sheen — José Luis Alcaine would repeat that trick when shooting Brian De Palma’s Passion (2012) — which, coupled with the production design, has elevated the film into an aesthetic marker of the Y2K era. But unlike so much art and media from the time, it isn’t nostalgia that has made it so enduring: coupled with Shu Qi’s mesmerizing screen presence — her mysterious glances at the camera during the opening manage evoke romantic longing, freedom, and memories of long nights out — the film’s prime achievement lies in how it both captures and transcends its historical context. (Wisniewski’s Reverse Shot piece smartly notes that the film “[tells] a story set in the present as a period piece.”)

It’s extraordinary how much Hou’s vividly rendered 2001 still captures the hangover from a promised future that never came, channeling the end-of-history melancholy also conjured by Ryū Murakami’s Tokyo Decadence a decade earlier and the digital lo-fi of Jia Zhangke’s Unknown Pleasures a year later. Loneliness, ennui, and spiritual emptiness run rampant in the gorgeous, glittery prison of the modern world that Millennium Mambo traps its characters in — toward the end, characters are even seen through the cold, omnipotent eye of a surveillance camera — and the detached style with which Hou approaches this hazy trip down memory lane forms a fascinating contrast with the emotional resonance its final moments nonetheless achieve.

Vicky drifts from one moment to the next in an unceasing pattern of youthful thoughtlessness, a conceit which, in lesser hands, could’ve easily made for a trite cautionary tale or even a reactionary warning of societal decay. But the third-person perspective, which implies an ambiguous remove from her difficult past, also suggest the possibility of change while acknowledging the past selves we leave behind. During the film’s final moments, Vicky looks back at her relationship with Hao-Hao one last time, remembering a tryst with her former beau during which she imagined him as a snowman, doomed to melt away when the sun comes up. “Making love was sad that day,” she says. “Even years later, she still remembered it.” And yet, as she moved on, the memories became the only thing tethering her to the sorrow she felt 10 years ago. Hou’s vision is bittersweet — but it is not hopeless.

Comments are closed.