Danis Tanović might be the most personal, visually compelling, and thematically thoughtful political auteur working in European cinema. And regrettably, his name will largely go unrecognized by even the most globetrotting and well-watched of cinephiles. With very few exceptions, Western film lovers have failed to properly appreciate Tanović’s best work, a sin that needs rectifying. With an indefatigable eye for style as political substance, Tanović’s rivals the best in the craft. His films are masterclasses in political subversion, human-first art, layered artificiality, and sensuality. Worth in salt on the line, this critic is comfortable declaring the filmography of Danis Tanović is a filmography worth the investment.

Tanović has directed (and released) nine feature films, a handful of documentary shorts, and two limited series, with several other projects coming soon. But only three of these efforts are widely available in North America as of this writing: No Man’s Land (2001), Cirkus Columbia (2010), and The Postcard Killings (2020). If there is one film the average Western moviegoer may have encountered while scrolling through the bowels of Letterboxd lists or Eastern European cinema, it would be No Man’s Land, his Academy Award-winner (for Best Foreign Language Film), which follows three soldiers on two different sides of the Bosnian War, trapped in a shared trench. It’s certainly a quality film, and it comes as no surprise it’s his most available title, but it’s also his first feature, and, like most first-time filmmakers, Tanović has matured as an artist in the two decades since his debut.

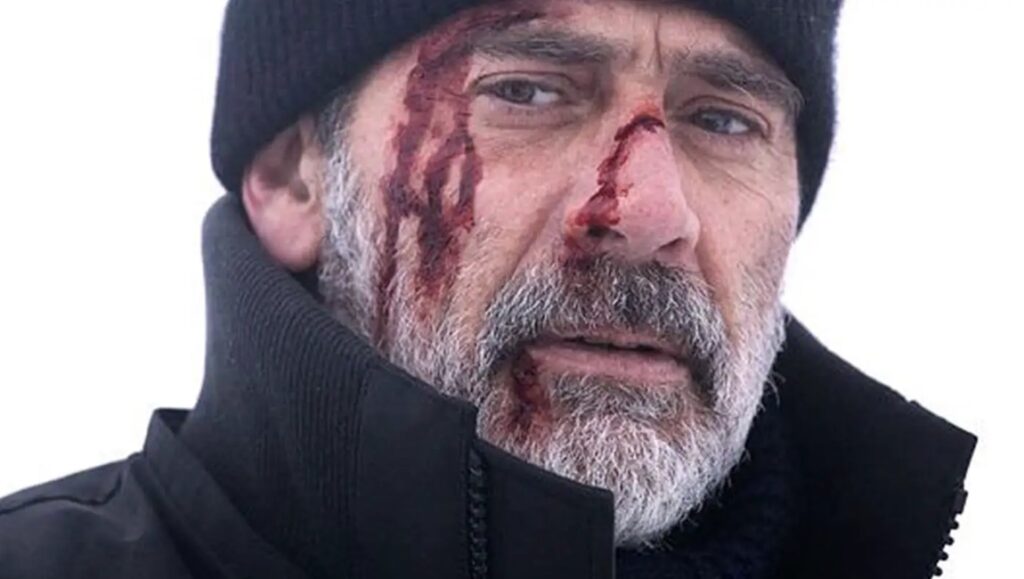

The Postcard Killings is one of the director’s two English-language films and stars Jeffrey Dean Morgan as a New York City detective chasing a demented killer (or killers) across Europe to bring his daughter to justice; it’s a movie that reflects a market and star capable of propelling Tanović closer to the mainstream. There are still many characteristic features of his artistry that leave their mark on the film, including a general skepticism toward policing, the frequent use of diegetic or in-world cameras as vantage points, and even taboo love. But although The Postcard Killings grows on this viewer with each watch, it’s also, unfortunately, his most insignificant feature to date.

Cirkus Columbia, the third of the director’s widely available films, is a masterpiece, without qualification. According to Letterboxd, however, fewer than 600 users have logged the title (compare that to No Man’s Land‘s 16,000+). If a reader is to take just one thing from this essay, let it be this: Cirkus Columbia is available for $3.99 on both Amazon Prime and Apple TV Plus. Set on the brink of war in Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1991, the expatriate Divko Buntić (Miki Manoklović) returns home to his small idyllic town in Herzegovina (specifically, the southern part of the country) and disrupts the lives of those around him in the process in a deeply sensual summer film where the political violently collides into the mundane. The effects of Yugoslavia’s breakup and subsequent onset of war are distilled in the complicated relations of one family, complete with a parable-esque and borderline incestuous relationship. Not unlike the great novels of Gabriel García Márquez, Halldór Laxness, or Günter Grass, watching a Tanović film demands relating the local to the national, the fictional landscapes to actual geography, and the personal to the political.

Moving beyond Tanović’s most immediately accessible works, it took three years for this writer to find a watchable version of Death in Sarajevo (2016), likely the director’s second-best film as a stylist, even if its rather blunt political analogizing will inevitably turn off some viewers. As of today, any potential screening requires a VPN to find the film, which is set in Hotel Europa on the centenary of Gavrilo Princip’s assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand, as the past-prestige hotel prepares to host a delegation of European Union diplomatic VIPs. Then there’s Triage (2009), which stars Colin Farrell as a devastated war-time photojournalist in Kurdistan, and which also requires some effort to find and can only be bought on Blu-ray; in a post-rental store world, no one can “accidentally” stumble across Triage on popular streaming services. Similarly, Tigers (2014), a dramatization of a real-life Pakistani salesperson’s struggle against the corporate iniquities of fictional baby formula companies (à la Nestlé), is exclusive to Zee5, a small Indian cinema streaming service that is available in the United States.

Meanwhile, L’enfer (2005), An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker (2013), Not So Friendly Neighborhood Affair (2021), and the director’s two TV series (Kotlina, 2022; Uspjeh, 2019), are virtually impossible to watch in North America — at least legally and easily. In fact, in order to watch these titles for this piece, Tanović himself had to send screener links. All of this is not to emphasize the esoterica of his filmography, but to state in no uncertain terms that, apart from Cirkus Columbia, the small sampling of Tanović’s filmography widely available in North America does not reflect the sum of the director’s great artistry.

The inaccessibility of these films testifies to the pathetic state of international film distribution and exhibition. Two of these films won the Jury Grand Prix at the Berlin International Film Festival — and all of them were made by the only filmmaker from Bosnia and Herzegovina to win an Academy Award. There’s a good chance he is the most accomplished filmmaker in the history of his country — perhaps even across the Balkans more broadly — and yet, absolute nada. It’s reasonable to assume there is an economic proposition involved, a perceived lack of interest in the cinema from a country with fewer than four million inhabitants, but at the end of the day, this excuse (masquerading as explanation) is just that — an excuse. As we all know: good cinema is good cinema.

Despite their lack of accessibility, Tanović’s films have nonetheless garnered considerable success at almost every turn at festivals and awards ceremonies. In addition to his two wins at Berlin and 2002’s Oscars honor (triumphing over the modern Indian classic Lagaan and the French film du jour Amélie), he has also been nominated for a Palme d’Or and two Golden Bears. He took home a Golden Globe Award for Best Foreign Language Film with No Man’s Land, and has elsewhere twice won the European Film Awards for Best Screenplay. His films have also won and/or been nominated for major awards at the Venice Film Festival, Jerusalem Film Festival, Cinema for Peace Awards, Istanbul Film Festival, and the New York Film Critics Circle Awards, among others. And he once made a film on a budget of €35,000 with amateur actors and a still camera that won two Silver Bears in Berlinale and was shortlisted for another Oscar. All of which is to say, by basically any qualitative metric, those who have seen his movies have loved them.

What follows this introduction is this writer’s carefully considered case for Tanović’s position in the canon alongside the likes of Rainer Werner Fassbinder, Jia Zhangke, Costa-Gavras, and Youssef Chahine as one of the great political filmmakers in cinema history. (Sergei Eisenstein will forever remain in a class of his own.) To better understand the artistry of Tanović, his propensity for humanist stories, his complex ideological filmmaking that bends and breaks the limits of fiction, and the film-to-film diversity of his poetics is to find a new filmmaker worthy of cinephilic canonization.

Bosnia, Genocide, and a Celluloid Documenter of Armed Conflict

As a multi-ethnic state, Bosnia and Herzegovina is (roughly) composed of 44% Bosniaks (a term that developed during Ottoman occupation to distinguish the Bosnian Muslims who spoke Serbo-Croat from the Ottoman Turkish), 32.5% Serbs, and 17% Croats, with Bosniaks being of Muslim heritage, the Serbs coming from an Orthodox background, and the Croats mostly ascribing to Catholicism. For context, and to grossly oversimplify one of the most complex modern conflicts, following the dissolution of Yugoslavia in 1991-92, Bosnian Serbs rejected a referendum for independence and supported the war that Slobodan Milošević’s neighboring Serbian government waged to seize Serbian majority territories in Bosnia and Herzegovina and ethnically cleanse its conquered territories. The Srebrenica Massacre, a genocide of more than 8,000 Bosniaks, became a violent emblem of the deadliest conflict on European soil since the Second World War. More than 100,000 people were killed in total, including about 30,000 genocided Bosniaks, and an additional 1.2 million were displaced through ethnic cleansing. And like all wars, the violence was not confined to the taking of life — as many as 50,000 women were raped — nor can any statistic account for the irreparable psychological and social damage. The siege of Sarajevo by the Army of Republika Srpska lasted an astonishing 1,425 days, the longest siege on a capital city in modern warfare, and resulted in the deaths of 13,952 people (with nearly 6,000 civilians accounted for). This summary is important, not just because it’s unfortunately easy to expect the average reader to be broadly ignorant of this profound tragedy, but also because, like the Shoah’s lingering effect on the German New Wave, it establishes the specter that haunts all of modern Balkan cinema.

Tanović’s feature directorial career started in 2001 with No Man’s Land, to date his best-regarded and best-known title. It’s also his most action-oriented film, though it remains far from an action film: two soldiers at odds during the Bosnian War find themselves trapped in a trench with each other and must work together to request assistance. Having written and composed the film as well, the director’s complete oversight enabled his thumbprint as a bonafide auteur to also begin in 2001. That his career would start with the Bosnian War appears predestined; he was a university student studying in the capital in 1992 when the war broke out. Forced to pause his studies due to the Siege of Sarajevo, he formed a film crew and followed the Army of the Republic of Bosnia and Herzegovina, becoming an unofficial celluloid documenter of the armed conflict. According to an Indiewire interview from 2001, “he shot over 300 hours of footage for the Bosnian army’s film archive.” Tanović’s career and worldview are, understandably, quite literally shaped by the war and the subsequent social fragmentation. “I realized that nobody was filming what was happening, which was astonishing,” the director told the Los Angeles Review of Books in 2016. “When you see a grenade fall in front of you, it makes an impression, you know? The most obvious thought was, ‘My god somebody should film this.’ So I went to my school. I broke into my school because it was closed. I took two cameras out and started filming. Then, I was doing more and more. That is how I spent two years of my life.”

In the decades that followed, he would turn his attention from the documentation of atrocity to the stories of ghosts created by war. Most literally, his 2011 short Baggage shadows a rather blue Amir (Boris Ler, one of the country’s most reliable acting talents) as he returns home from Sweden to collect the bones of his parents murdered in the genocide. He quickly realizes it’s not them, and sets off back to his family in Sweden as he gets wind of someone who knows where his parents’ remains rest. What this means is never voiced, and it never needs to be: the ghosts of ethnic cleansing and the ethnically cleansed cohabitate in Bosnia where, as of 2011, the fate of 10,000 people remains unknown. The war lingers in No Man’s Land, Baggage (included in the collection 11’09’’01 September 11), L’Enfer, Triage, Cirkus Columbia, and — of course— Death in Sarajevo.

No Man’s Land never stoops to the bothsideism that the premise could easily have been wrung into. Importantly, Tanović is never unclear whose blood is on whose hands; that said, he does play with the viewer’s predispositions to these geopolitical questions utilizing interpersonal power dynamics. The answer to the question “who started the war?”, asked literally in the screenplay, changes depending on which of the men in the trench has possession of the only gun. The cunning political criticism goes deeper than the immediate answer to the factual question: the presentation of the truth carries more weight than the simple facts. The film’s core marketing mentions just two soldiers, but there’s actually a third — a wounded Bosnian lying on an S-mine. The award-winning feature ends with this soldier’s fate being decided in a game of showmanship by the United Nations peacekeepers and the well-intended but gullible and politically malleable Western media ecosystem. Like real life, the United Nations — whose incompetence and negligence failed to prevent Srebrenica (see Jasmila Žbanić’s Quo Vadis, Aida? for a cinematic introduction) — damns the soldier through inaction. The symbolic and very real physical power that the gun imparts to its holder in No Man’s Land, combined with a typically Balkan lack of confidence in the UN, points to the empty gestures from the hegemonic powers and the forgotten or socially contested recognition of the Bosnian genocide in parts of the world.

Human-First Art

His second film, L’Enfer or Hell, carries with it the legacy of Krzysztof Kieślowski, who penned the screenplay alongside Krzysztof Piesiewicz as part of their proposed “Heaven, Hell, and Purgatory” trilogy. Kieślowski died in 1996, and the script ended up in the hands of Tanović, who lived in Paris and Brussels for much of the late 1990s and early 2000s. The first of his many films that operate outside of his native tongue, the French-language Hell stars three formidable acting talents in Emmanuelle Béart, Marie Gillain, and Carole Bouquet as adult sisters with their own coping mechanisms for navigating a traumatic event from their childhood. But Tanović doesn’t allow pain, violence, or even trauma to leave the intimacy of the home. And with clear references to the films of Kieślowski, as well as classical Greek tragedies, the inciting event involves one of the daughters walking in on the girls’ father and a naked young man together. Looking forward, the inciting events of Tanović’s films — murder, eviction, sexual encounters, and possible crimes (genocide, infanticide) — almost always come from the hand of a loved one, a co-worker, or a neighbor. It’s not the stranger who scares Tanović; it’s the neighbor who might have murdered your parents, the father who evicts the mother, the fellow soldier who is just like you but whose parents happen to practice another religion. These neighbors catalyze the action, trauma, and violence in Tanović’s oeuvre.

In Triage, his third feature and the better of his two English-language movies, Colin Farell plays Mark Walsh, a war-time photojournalist who occasions a very close call in Kurdistan. Although the screenplay is adapted from a novel by Scott Anderson, Mark suitably shoulders many of Tanović’s burdens, including, most obviously, his former vocation as an image-based documentarian of armed conflict. One conversation between Mark and Joaquin Morales (Christopher Lee), the psychotherapist and Spanish Fascist-sympathizer grandfather of Mark’s wife, straddles the boundaries of fiction. “Tell me, does the camera act as a kind of buffer for you, to distance you from your surroundings?” asks Joaquin, in an intimidating performance from Lee, overlooking the wheelchair-ridden Mark. “Sure. I suppose that’s why a lot of photographers have been killed throughout the years. Looking through the camera, it is easy to forget that the things that are happening in front of you are actually real,” Mark answers without trouble. “Or sometimes it fails. Sometimes the real world takes over,” the psychotherapist interrupts. The psychological insight cuts through Mark, sending him into a vulnerable, emotional fit.

The erudite insight works on the meta-level too. The lens of a camera, a tool representing generic artistic capacity, possesses the potential to highlight real human issues. Joaquin intends his insight to explain inaction and the psychological impact of seeing through the viewfinder, identifying the crux of Mark’s PTSD, but it works for the real-world audience almost in reverse. Cinema can teach us about the world; perhaps it would be even more accurate to say cinema should teach us our world. To use the words of the Depression-era photographer Dorothea Lange, whose legacy of dignified photography of poverty is evoked in An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker, “A camera teaches you how to see without a camera.” Pure entertainment, or what Tanović refers to as “this Avengers shit,” doesn’t do this. Only human-first art can. And Tanović emphatically makes human-first art.

As for the artwork he creates, there is only the real world. He describes the undergirding motives for a few of his films through what he wanted to communicate to the primary audience:

“I always make a film with an audience in mind. I made Cirkus Columbia for my parents because I know they love Italian films and I loved Italian neorealism, and so I tried to make Bosnian neorealism. I made it for them and I wanted to tell them “You fucked up, it was a beautiful country and your generation fucked it up and killed our generation.” I made Iron Picker because I couldn’t believe that the same people who saved their neighbors from snipers in the 90s are letting their gypsy neighbors die over something petty like bills. I made Death in Sarajevo for the people of Sarajevo. I made it for my neighbours. I think Bosnia is the most beautiful country and I want it to work. I want to build to a better future. I want to have hope.”

While Tanović may use “neorealism” when talking about Cirkus Columbia, “realism” fails to fully apprehend and reconcile the nuances of the artistic vision shared across his filmography. The editing of The Postcard Killings, L’Enfer, and Triage in mixed states of consciousness and confused chronologies, and the effective though strange documentarian narration of Tigers, actively reject various aspects of the realist project. As an occasional composer himself, the director cares tremendously about music, and as such, the majority of his films are more scored than the average neorealist picture; he also uses mostly professional actors, another characteristic alien to neorealism. (On both of these fronts, An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker, his most significant stylistic departure, should be considered exempt.) He does something with the real, but not through a strictly realistic cinematic design; these creative instincts more or less delineate his artistry. In his interview with the Los Angeles Review of Books, Tanović frames his decision to pick up a camera during the Bosnian War in the language of participatory action: “When I was 22 years old, there were basically three choices: you can run away, you can hide, or you can do something about it. I guess I am kind of a guy who wants to do something.” In the same interview, he compares the political goals of Bernie Sanders with his artistic goal: “Trying to push humanity to a certain place.” In line with the political spirit of his filmography, he’s no stranger to actual politics either. Tanović is the co-founder of Our Party (Naša stranka), a social-liberal and multi-ethnic political party in Bosnia and Herzegovina, and has long been a champion of social and educational programs. Correspondingly, some of his films, especially An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker and the 2021 documentary short When We Were Them, work perfectly fine as social-liberal humanitarian propaganda.

As a director, Tanović consistently and almost obsessively centers on the victims of conflict and poverty rather than the producers of violence and the hoarders of power. In An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker, Tanović elevates the Roma minority in a dramatization of a real-life news story about the lack of healthcare accessibility for those without insurance cards. The focus never drifts from Senada Alimanovic and Nazif Mujic, playing themselves in the dramatized account of the news story. When We Were Them documents the thousands of migrants and refugees stranded in Bosnia’s war-torn north and, in its short 15 minutes, unearths national histories of violence and oppression to plead political action. Cirkus Columbia depicts the final moments of normality for a Bosniak family before the region spurs into violence; the emotional glue in Death in Sarajevo is an old laundry worker from the hotel basement who leads a union strike in defiance of poor working conditions.

When it comes to visual design, a related signal trademark of Tanović cinematography, consistent across the different cinematographers he has worked with throughout the years, is the use of close-ups and extreme close-ups on human features, with a special focus on hands. In L’enfer, one of the final images involves one of the film’s central women squeezing a flower with her hand; the symbolism communicates even more under the pressure of the intimate lens. Amir’s shaky hand in Baggage picking up the watch of a dead parent comes close to being one of the most touching images so far in Tanović’s career. (The symbolic meaning of the watch representing time’s role within the memory of genocide and war shouldn’t be lost either.) An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker might use the director’s preferred shot type most abundantly, especially when doing the things that hands tend to do best: work. And the opening to his short in 11’09’’01 September 11 is a woman’s face that takes up the entire vertical space of the screen as she stares at the ceiling above her bed. Tanović changes the angle once or twice, shows her alarm clock, and then returns to her face even at an even closer position than before: the ticking of time notably weighs on this face. Then, we’re given one more angle from her side before we get an extreme close-up of her fingers playing with the red fabric of her clothes, the contours of her face hardly recognizable through the cloth. Usually utilized at moments uniquely human — moments of grief, work, and even food prep (no other animal cooks!) — the close-ups produce snapshots of humanity without abusing their power.

In the rare instances where his films do not center on victims of social systems, everyday heroes disrupt the status quo — perhaps a philosophical inheritance from his Marxist father. From an interview on Tigers in 2018: “Conflict is the heart of drama, but I look for stories that remind us that most people, placed in awful circumstances, respond by being incredibly brave and compassionate. Aamir and his family risked everything to take on a huge corporation. Their story is inspiring, but it also reminds us that we are constantly being manipulated and that we all have responsibilities to challenge the forces around us, whether they’re corporations or governments or despots.” The mystery of Kotlina also unearths a plot of international crime and corruption. In a more cynical representation of heroism, Jacob Kanon (Jeffrey Dean Morgan) relentlessly pursues information about his missing daughter in The Postcard Killings, and Ayan (Emraan Hashmi) bravely blows the whistle against his baby-killing place of work in Tigers. Even the soldiers in No Man’s Land are not, strictly speaking, harbingers of terror; they are more like its measly custodians, as much victims of war as they are its means of execution.

Labyrinth of Linkages: Layered Artificiality and the Ideological Deconstruction of Fiction

Teases of Tanović’s most personal aesthetic and consistent thematic choice — a complex, layered dialectic between reality and fiction (sometimes as docu-fiction) — come as early as No Man’s Land through the role of television reporters and their many intrusions, as well as an often comedic and playful use of translation (memory serves, there are six languages spoken in the film: Bosnian, English, French, German, Italian, and Serbian). “I don’t think there’s so much difference between making documentaries and feature films,” the director stated in 2001. Any invested viewer of his is well aware of this indistinction. That’s not to talk only of substance, source material, or thematic power; throughout his constantly evolving style, the very aesthetics that cohere in Tanović’s filmography are layered realities where varied visions of the real fold into one another and create something new. The best allusion might be New Journalism, a creative response championed by writers like Tom Wolfe and Norman Mailer to news reporting in the 1960s-’70s that challenged the “voice of God” house style of outlets like the New York Times and the BBC. If New Journalism dresses reporting in a panache literate style (of which Werner Herzog’s documentaries are a good cinematic representation), Tanović provides the inverse. His layered realities undress fiction with the grittiness of real life. Most powerfully, An Episode in the Life of an Iron Picker provides a social-realist dramatization of a crisis with the people it actually happened to playing themselves; it’s not a documentary — or, if it is, it applies the philosophy of New Journalism to the documentary and “literatureizes” it. As a docu-fiction, Iron Picker certainly can’t be deemed a regular fictional(ized) feature either. The most obvious precedent for the documentary-fiction hybrid comes out of the late-stage films of the Iranian New Wave, including the work of Jafar Panahi, where the written or predetermined elements blend seamlessly with the unscripted real world. A more recent comparison might be Martin Scorsese’s pseudo-documentary Rolling Thunder Revue (2019), where real footage and fictional material merge. More often than not, Tanović will primarily work with a fictional or dramatized story (rarely documentaries) and dress the screenplay down to distill the real social issues at play, occasionally blending in real-world images too.

Tigers demonstrates the complexity that this dexterous filmmaking can acquire. As a fictionalization of Pakistani headlines surrounding the ever-present Nestlé baby formula scandal, the film structures itself around the creation of a messy (and real) documentary about a salesperson-turned-whistleblower (Ayan, based on the real-life Syed Amir Raza Hussain) who comes forward with evidence that Lasta, a fictional company, has been knowingly marketing and selling an infant formula product that they knew to be responsible for several infant deaths. Originally scheduled for production with the BBC, who backed out in 2006 for fear of being sued by large companies (such as Nestlé), Tigers opts for a non-linear fictional story that makes use of real-world media, heightening the audience’s awareness of the actual infant formula problems and evading charges of serving as a feel-good entertainment flick. The generic Hollywood version of the story is much easier to envision: think of 2019’s excessively mundane Dark Waters or the hardly memorable The Report. The version we’ve been blessed with outclasses the most recent mainstream bearers of the sub-genre. When Ayan visits the hospitals to learn about the effects of the formula from the doctors, Tanović and longtime cinematographer Erol Zubčević depict real, suffering infants. Even an uninformed viewer will pick this up, seeing as there is clearly no room for a special effects budget; if they don’t, the closing credits spell it out right after revealing that “Ayan” is now a taxi driver in Canada and that the documentary was, indeed, real: “The other sick babies shown were found in hospitals during the making of this film. This is a story that keeps repeating itself.” The inclusion of real infants enhances the film’s emotional impact and outright enrages the one’s empathetic faculties.

Even in production, politics are never far off. The Indian-produced and Hindi-language Tigers features Emraan Hashmi, a beloved Bollywood leading man, in the role of a Pakistani citizen-hero. A proponent of pluralism and the disintegration of ethnocentrism, the Bosnian filmmaker likely intended to contribute a small part to the Indian-Pakistani social division by normalizing a positive image of Pakistan. (Although, it’s also possible it was just impossible to make the film within Pakistan; in this case, Tanović still made the decision to not rewrite the location of the already fictionalized account inspired by true stories.) Unfortunately, this may have also contributed to the film’s struggle to find an audience. The production is nothing radical — plenty of Indian films feature Pakistani protagonists — but, combined with the already risky undertaking of damaging the image of large multinational pharmaceutical companies, it may have affected the film’s Indian release despite winning international awards, as Hashmi alleges. This isn’t Tanović’s only production with a somewhat striking production arrangement. His 2019 miniseries Uspjeh (Success), about four strangers connected through violent crime in Zagreb, compiles a pan-Balkan crew with its Macedonian writer (Marjan Alcevski), Croatian production company, and Bosnian director and showrunner — the cast comes from all over the region too, including another appearance from Boris Ler.

Film scholar David Bordwell quotes Leo Tolstoy on a “labyrinth of linkages” to describe the narrative and poetic complexity of Christopher Nolan’s formal project, a project delineated with cross-cutting, intense subjectivity, and integrated lines of story action. Nolan and Tanović have very little in common, but Bordwell’s “labyrinth of linkages” could also describe Tanović’s ideological project and formal execution, culminating in Death in Sarajevo. Not unlike Nolan’s famed multi-plot structures (though absent the ambitious cross-cutting), Death in Sarajevo witnesses three parallel narratives unfold in Hotel Europa on June 28, 2014. The first comes from the source material, a play by Bernard-Henry Lévy titled Hotel Europe, which is in execution the two-hour monologue of a French EU delegate preparing a speech in Sarajevo about, broadly speaking, “Europe.” The same French actor (Jacques Weber) who plays the lead in Hotel Europe takes on a reduced role in Death in Sarajevo; his only function is to fumble the recitation of the ceremonial speech from the isolated confines of his hotel room. The second and most interesting thread follows a television reporter, Vedrana (Vedrana Božinović), conducting interviews about Bosnian history from the roof of the hotel. Her most important interview is with a man (Muhamed Hadžović) who proudly shares his full name with Gavrilo Princip, the assassin of Franz Ferdinand. The last of the three takes place in the basement among the downstairs workers organizing a labor strike on the day of the delegation to maximize news coverage. As the three storylines converge, a random act of violence (in the neorealist tradition of Bicycle Thieves) interrupts an overarching movement toward understanding and a reconciliation of the pluralistic imaginations of the Bosnian future on display.

Within this web of complex social stories — which, non-conspicuously, move vertically down the hotel as they become more grounded in daily life in Bosnia and Herzegovina — Tanović utilizes his most ambitious layering of artificiality and truth thus far, through a maze of digital screens and personal reflections not unlike the work of Michael Haneke, albeit with a humanistic touch. Much of what is shown of Jacques’ hotel-room speech practice comes from a hidden security camera. The livestream news coverage from the roof of the hotel takes place on multiple levels: the largely background live interaction between Vedrana and her interviewees; the perspective of the actual (lightly grainy) camera recording; and, finally, the obstructed and double-framed vantage point from the digital display of the news camera. In both settings, digital technologies peer into the constructed imaginaries of the lives of the elite: the hotel higher-ups, the media, and Europe’s politicians. (Haneke’s Benny’s Video makes for an interesting comparison through its similar focus on the moral responsibility for murder and through its use of in-world digital screens to reveal and conceal, as well as its framing of Benny’s murder through the Balkan War; Tanović’s Austrian peer, however, creates a much darker and more provocative world than anything in Tanović’s filmography.)

The basement cinematography, again by Zubčević, uses high-contrast and low-key lighting to establish a thriller atmosphere that grounds the film in a way that the de-attached, artificial worlds of the television news reporters and elite European Union representatives can never replicate. The cold gray-blue color of the basement alienates itself from the warm outdoor colors of the rooftop, creating separate worlds for the haves and have-nots, and the ambition of such a project crescendos in a blunt but by no means shallow political analogy. In something of a mirror for Balkan society, Hotel Europa begins collapsing through the blundering of internal politics and the neglect of the poor workers, whose strike (or attempt to secure a better life) is hindered by authority-sanctioned violence. It’s difficult to be more straightforward than that when discussing the film, but the layered artifice presents a complex ideological labyrinth of linkages between the fictional and the real. How can the cycle of artifice, inauthenticity, and political meandering be broken? Is the violent option all but inevitable — terrible as that may be?

Another pattern emerges right on the surface of the stories Tanović has preferred to tell a few decades into his career: things may not be what they seem. This is seen most obviously in his literal mysteries (the series and The Postcard Killings), but also in Triage and L’Enfer. Major plot points shift on a dime and challenge the viewers’ preconceptions about truth. The shiftiness of plot complements the stylistic labyrinths of linkages he creates in his visual storytelling. False accusations, the reconstruction of memory, selfish motives, and personal vantage points shape an individual’s response to facts. Personal experiences shape our reception of history and culture. The conclusions to The Postcard Killings, Triage, and L’Enfer all reorder the films’ presentation of truth — arguably in ways centered on the location of power in truthmaking — in the final moments, contributing to Tanović’s larger project blurring the fictionality of fiction.

A Diverse Poetics

There are a variety of ways to approach the films of any great filmmaker, and this is predictably also the case for Danis Tanović. This essay has focused on his innovation of style as political substance, but one could just as easily look to the great Bosnian director for a masterclass in sensuality, or to study a case of genre transcendence on par with Christian Petzold, a filmmaker whose quiet landscapes, period colors, and niche personalities share quite a bit in common with the director of Cirkus Columbia and L’Enfer. With that acknowledged, any discussion on Tanović without an account of his diverse poetics would be incomplete. There may be a consistent ideological throughline from No Man’s Land to The Postcard Killings, but the formal (though not necessarily thematic) poetics he employs adapt and evolve with each project. (In this sense, Tanović is right to call Cirkus Columbia a neorealist picture.)

As a filmmaker with an excellent understanding of what makes a great shot as a shot and, separately, what makes a great shot as a composite element in the construction of a scene, there are several scenes within his filmography that are nothing short of indelible, and may be in the discussion of the very best images of the 2000s and 2010s. In one of these scenes, from Cirkus Columbia, Azra (Jelena Stupljanin), the younger red-headed fiancée to Divko Buntić (Miki Manojlović), who has just returned to Bosnia/Yugoslavia from Germany, leaves her partner in tears after realizing he is using her to provoke his separated (but not divorced) ex-wife. Wearing a flattering pink summer dress, she paces past the stone houses and through the scenic greenery of the small town in Herzegovina where the film is set. Divko’s estranged son, Martin Buntić (Boris Ler, again), chases after the crying Azra, who has been nothing but kind to him since arriving in town not long ago. The red of Martin’s shirt is so strong against the verdant park-like surroundings that he becomes immediately noticeable even as a small figure in the distance. She runs away to a tree in a nearby field as he nears, brushing away her tears while fleeing. He pursues her, notices her emotional condition, and provides comfort before moving in for a kiss. She initially resists, before deciding to act on her desires. As they have sex against the tree, Divko’s missing and sickly black cat, whom the two have been searching for together for much of the film, jumps from the tree and flees.

Despite being taboo (she was on track to be his stepmom, but isn’t), the scene’s astonishing sensuality denies disgust, even though there is a post-intercourse moment of realization of what this means for her relationship with Divko. For most filmmakers, this would have been the real trouble; Tanović, however, breezes through the moral quandary with ease. The red and pink of Martin and Azra, respectively, make sense against the green backdrop of Herzegovina (and help cover up that their relationship doesn’t). When she initially seeks comfort and rejects Martin against the (phallic) tree, she turns toward him rather than away from him — a seemingly deliberate choice on her part to remain open to the possibility in the first place. Azra clearly receives pleasure from their sex too, as she moans in closeup, chin raised skyward. In fact, the sex centers female pleasure rather than male desire. The distracted forbidden lovers fail to even notice or care about the cat, a testament to the blissful moment of their sexual expression and falling into tunnel-vision passion, in the great tradition of summer films. Through this wonderfully titillating scene, Tanović and his entire team of filmmakers turn what should be a troubling encounter into an alluringly passionate one. By the end of the film, light Oedipus Complex and all, viewers will be rooting for the two to end up together.

Another minor moment of sensual pleasure, with a twist, comes in the first episode of Kotlina, Tanović’s 2022 show about a murder in the National Museum of Sarajevo. The scene takes place at a party of some sort, and strobe lights attack the viewer almost vengefully. Two beautiful women dance around each other with mutual and playful sexual interest. Two men watch them from the other side of the room as they come in for what looks like a kiss. And then… we cut to a lonely man at a bar. The strobe lights already made the two Sapphic lovers difficult to look at, a seemingly deliberate denial of male voyeurism into a private, pleasurable moment for the two women. Only after teasing the sexiness of the random encounter does the cut indict such gazing.

From Iron Picker to The Postcard Killings, each film calls for vastly different styles that, as shown earlier, share not unrelated ideological ends. Iron Picker is the most realist work Tanović has made thus far, with a minimal score and a single still camera. The performers are non-professionals, simply acting out something that’s already happened to them; like Robert Bresson, Tanović doesn’t seem to ask for much beyond line readings and to be authentically themselves. The film’s title comes from the eponymous man’s makeshift job of finding metal in a scrapyard to sell for cheap, a task shown in tedious detail for such a short film. Its most noticeable stylistic carryover from Bresson appears to be the fascination with intense closeups of objects, faces, and especially hands. These hands are active, tending to household chores or cooking; like the people they belong to, they can’t afford to be idle. The camera sees less color than in virtually any of the director’s other films; the Bosnia of the Romas is cold, dark, and mean — not a warm summer. As in many of the Italian neorealist films, kids play a major role on screen here, which is something of an aberration in Tanović’s larger filmography. But stylistically speaking, Iron Picker stands out as something altogether different from both that tradition and from the director’s larger oeuvre.

The Postcard Killings, led by Jeffrey Dean Morgan, also applies a different set of formal poetics, operating in a much darker and more genre-inflected style. In one scene, Morgan’s Jacob Kanon peers in on the police investigation of a young married couple who are suspects in a series of serial murders that include Jacob’s daughter. (One of the film’s major twists is the couple are siblings, bringing back the somewhat puzzling incest-adjacent subject matter that remains difficult to intelligibly parse.) The investigation, at least for this viewer, works as something of a turning point from understanding the couple as potential victims to potential killers. Nothing in their story is terribly damning, allowing the cops to justify their release of the couple and to maintain a degree of mystery that the crime genre would be boring without. But the scene leaves an uneasy pit in the viewer’s stomach, largely because of its visual presentation rather than any expository breadcrumbs or information revealed in the questioning. The “husband,” Mac Randolph (Ruairi O’Connor), sits on the right of a table with a cop, a tripod camera to the left. A maze of mirrors above the table creates a black void at their vanishing point. After the cop leaves, cinematographer Salvatore Totino (Spider-Man: Homecoming, The Da Vinci Code) keeps the camera on Mac and the now empty other half of the table without reframing or pushing in. In a parallel setup with “wife” Sylvia Randolph (Naomi Battrick) on the other side of the table, in a different empty room, editor Sean Barton (Return of the Jedi, The Fly II) creates the illusion that they are on the other side of the mirror from each other rather than the room of cops. The score, an ambient drone, cuts to silence. We get no true closeup of either after the cops leave, although the camera does move a bit closer to Sylvia. But Totino’s camera takes care to keep its distance, denying the exact sort of profound humanization that is expressed in the closeups of Martin and Azra’s copulation in Cirkus Columbia. As the scene ends, there is no doubt that something is not quite right with Mac and Sylvia — an unsettling truth entirely communicated through formal technique.

Tanović’s Place Among the Great Directors

Few filmmakers in Europe, or the world for that matter, have as distinct yet flexible a style as Danis Tanović while also managing to use style as political substance. The experiential presentation of a good story, for the Academy Award-winning Bosnian director, is something that “can slightly push the society forward,” and that carries with it a brunt of responsibility. (For himself, that responsibility translates to a center-left humanistic visual style.) And though he does so in a very different way, Jean-Luc Godard might be the best example of transforming visual style into ideology (rather than simply as a vessel for ideology) — and yes, this analogy is bound to ruffle the feathers of canon purists. Godard frequently distilled Bertolt Brecht’s alienation effect into its natural Leftist expression. Tanović does not make intentionally alienating films; he’s too much of a humanist for that. It also seems that he believes in the democratization of art too much to only make films for educated cinephiles like Godard. (No slander intended: Godard is of course one of the best to ever do it.) Instead, Tanović’s films are actually aimed at the average proletariat in a way that the more Leftist Godard’s films could never be.

There is no adequate comparison for Tanović, and this alone perhaps corroborates the value he adds to global cinema. The most obvious comparisons are his own sources of inspiration, like the great Polish director Kieślowski (who did not mentor or “study with” Tanović as some outlets have claimed), the Italian neorealists, and Michael Cimino’s war film The Deer Hunter. (The latter’s influence is most felt on Triage for somewhat spoiler-ish reasons). But even the sight of these three influences varies widely within the director’s work, and he never constricts himself into becoming a mere custodian of any of his influences. Cimino’s influence comes through mostly in shared thematics — specifically as related to explicit war films that document the memories and internal trauma of violence, a theme that is doubtful to ever leave Tanović’s art — but also in Tanović’s crime-centered work of recent (the two TV series and The Postcard Killings); both filmmakers identify and capture the complexity of memory in the process of understanding violence and its impact. As for the neorealism influence, which is mostly only evinced in the director’s only docu-fic (Iron Picker), it’s never going to be seen as the purist’s definition of the filmmaking tradition. Instead, Tanović uses real-world media — historical events, news stories, documentary footage, dying babies found in real hospitals, etc. — as a tool to bridge his compelling fictional storytelling to real-world representation. L’Enfer, for example, is a hyper-stylized work that comes together through complex animal-based symbolism and thematic colors — a film that very few, if any, realism purists would ever twist themselves to make.

And then there’s Kieślowski, who may be the most-cited point of comparison. But he was a more spiritual director where Tanović is a humanist; religion almost never comes up in his films. There’s an adhan in Baggage, a few Islamic references in Triage, and some priest sightings in Cirkus Columbia, but all of these are religious only in a sociological way, a far cry from the Three Colors trilogy. Instead, Tanović’s inclusions function only to identify people as religious; the camera is never truly interested in the transcendental. His L’Enfer is more humanist than the original script, as has been noted before, though he indulges, or honors, the departed Kieślowski with the film’s final major speech, a thesis defense, from one of the sisters, a moment so lofty it almost feels strange in Tanović’s filmography: “Tragedy highlights human vulnerability, whose suffering is provoked by a combination of human and divine acts. That is why tragedy is not possible in modern life. Our society has lost faith… The best we can do is live out a drama.”

In our online correspondence with Tanović for this piece, the director mentioned Federico Fellini, amongst many other filmmakers, as one of his favorites. Fellini is an interesting predecessor because he’s known for marrying the Italian baroque tradition with dreamy fantasy. Fellini is most known for these qualities in films like 8 ½, but he began his career as a neorealist and only later moved into a more surrealist space. Tanović, by contrast, coming well after the heyday of neorealism, blends and borrows from the tradition while never inching toward fantasy (at least, not yet!). But the two directors’ distinct styles are of a piece: both marry realist inclinations to other ambitions.

The pan-European, non-nationalistic, and pro-pluralism politics of Our Party (Naša stranka), the political party Tanović co-founded, finds an artistic champion in his complex style(s). And the voice that has been shaped by his time and place — as a Bosnian born in the former Yugoslavia, coming of age at the dawn of war and ethnic cleansing — amplifies an experience known to many but undeniably minimized in post-WWII European cinema; war in Europe did not magically vanish with the founding of the European Union or the end of the Shoah. Despite the (near-)universally accepted fact that the Balkans are part of Europe, the region is not always treated this way. The former British Prime Minister Tony Blair once remarked, “Kosovo is right on Europe’s doorstep.” If it’s on the doorstep, does that cast Kosovo, a small country to the southeast of Bosnia and Herzegovina, as an Asian nation? No, Blair is just wrong. He’s also representative of the regions’ normal treatment within the Western-centric political imagination. To use the words of journalist Misha Glenny in The Balkans: Nationalism, War and the Great Powers, 1804-1999: “For many decades, Westerners gazed on these lands as if on an ill-charted zone separating Europe’s well-ordered civilization from the chaos of the Orient.” By neglecting, overlooking, and flat-out ignoring the work of Balkan filmmakers, and specifically Danis Tanović, we repeat this line of thinking on an artistic level. It’s past time to rectify that, and you can start with Cirkus Columbia, currently available for rent on both Amazon Prime and Apple TV+.

Comments are closed.