The inimitable internal torments of David Cronenberg’s Dead Ringers are colored in bloody red and sterile chrome, starting with the melancholy anatomical figures and pointed medical instruments of the opening credits. Cronenberg has described his opening credits sequences as “a vestibule,” with all the bodily connotations that implies, and the medieval quality of the drawings combines with Howard Shore’s score to evoke the agony and ecstasy of being medically examined. The film takes place in a world of metallic grays and closed-off sets, with occasional incursions of sensual scarlet pleasures — the films’ occasional trips outside to normal coloring are a bit startling. It’s a surgical aesthetic reduced to the essentials a la a two-color Rothko — the dead steel of a speculum used to look into the blood-giving life of vaginas. (One girlfriend of Elliott’s, who knows what she’s gotten into, has an appropriately chilly pallor with coppery red hair — she’s practically part of the décor in their apartment.)

We’ll be with the examiners over the course of the rest of the film, starting with their childhoods as the sort of boys who were always a bit too detachedly interested in internal workings and the biology of fertilization to win over girls. They are the identical Mantle twins, Beverly and Elliott, both played as adults by Jeremy Irons in the kind of performance that the Academy Awards likes to recognize a few years after the fact, with a different movie that doesn’t make their skin crawl as much. (He’s helped by some groundbreaking visual effects that allow him to nearly seamlessly share scenes with his other performance.) They’re among the top gynecologists in Toronto, and they work and play together, swapping patients for work as they see fit; the dominant, misogynist Elliott seducing what he sees as the more attractive specimens before passing them on to the more intellectual and codependent Beverly. (Their names give away the initial dynamic, and the film knows it.) “You haven’t done anything unless I know about it,” says Elliott to Beverly, and he shares a pair of identical twin escorts he’s hired to prove his point.

Codependent relationships tend to require an outside force to make the break happen, and here it arrives in Geneviève Bujold, playing the infertile actress Claire Niveau and possessing the most clinical version of pussy magic in the form of a trifurcated cervix, rendering her forever infertile and with heavy implications about her lack of need for any kind of contraceptives. Elliott fucks and forgets her once he realizes she’s using them for prescription drugs, but Beverly’s fascination with her deformity turns into something more all-enveloping as she penetrates his sterile bubble with mordant wit and unexpected self-confidence: she brings bondage kink in the form of medical clamps and rubber hosing, she mothers him after nightmares, she feeds him her pills until he’s dependent in a whole new fashion. She inevitably finds out the “positively sick-making” truth about her dynamic from the plummy gossip of a one-scene character, but her confrontation with the twins in a restaurant cleaves Beverly in two: between his old life and his new desires. This is later rendered as a surreal metaphor via a nightmare scene of Claire cutting the twins apart with her teeth.

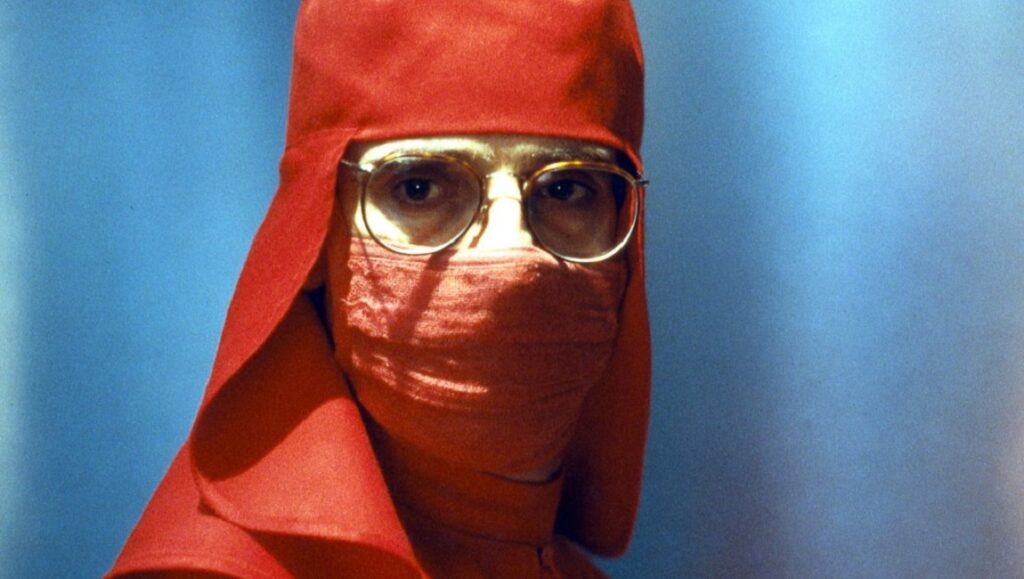

The real-life inspirations, the Marcus twins, were such an embarrassment of riches as a horror story that Cronenberg and co-writer Norman Snider could crib a few real-life incidents for their own purposes. The sequence of Beverly pulling off a patient’s anesthesia mask and huffing from it to “slow everything down” was not entirely drawn from the filmmaker’s imagination. But it’s a testament to a refusal to settle for just plain facts, no matter how compelling, that Dead Ringers gets taken to a more surreal place that only cinema could have achieved. It’s this scene that finally showcases the infamous, movie-defining “gynecological tools for mutant women” that Beverly conceived for operations, and they sit in contrast to the inexplicably scarlet medical robes, shot through with religious connotations as Beverly is dressed for surgery like he were the Pope. It’s a Grand Guignol exaggeration of the doctor’s sincere belief in his profession/obsession above all else, and the culmination of his extended drug-induced psychosis, triggered when Claire leaves him alone with his pills to go shoot a film. Beverly’s turn into a grotesque funhouse mirror of his brother’s views on women is where boundaries and identity start to properly blur: in his bloodshot eyes, all women are mutants inside, doomed to lose the interior beauty contests that Elliott quipped about in an earlier scene. The claw-like tools that suit their deformities need to be commissioned from a metallurgical artist as a result, but Cronenberg has never been inclined to deny aesthetic beauty, no matter how ugly its origins: Beverly needs to steal them from the gallery windows when his artisan decides they’re now his own art pieces.

When Elliott begins the resynchronization of their relationship by deliberately hooking himself on pills in his own right and becoming codependent, the slight swap in their dynamic is complete, even if the overall shape is forever warped. Irons finally starts putting his own flesh on display twice over, with both twins falling into living in squalor and racing to oblivion with one last operation, with the fundamental maleness of those tools meaning they serve their ultimate purpose. And yet, there’s still an aftermath, a final extension of this Dead Ringers’ increasing stasis and one last journey into reality before a retreat back to the dirty, bloody womb. All the great tragedies involve evil deeds and theoretically avoidable fates, but even with the real-world scaffolding built into its origins, only Cronenberg could have conceived of the specifics of this rise and fall in its mirrored surfaces and subconscious bloodlusts.

Comments are closed.